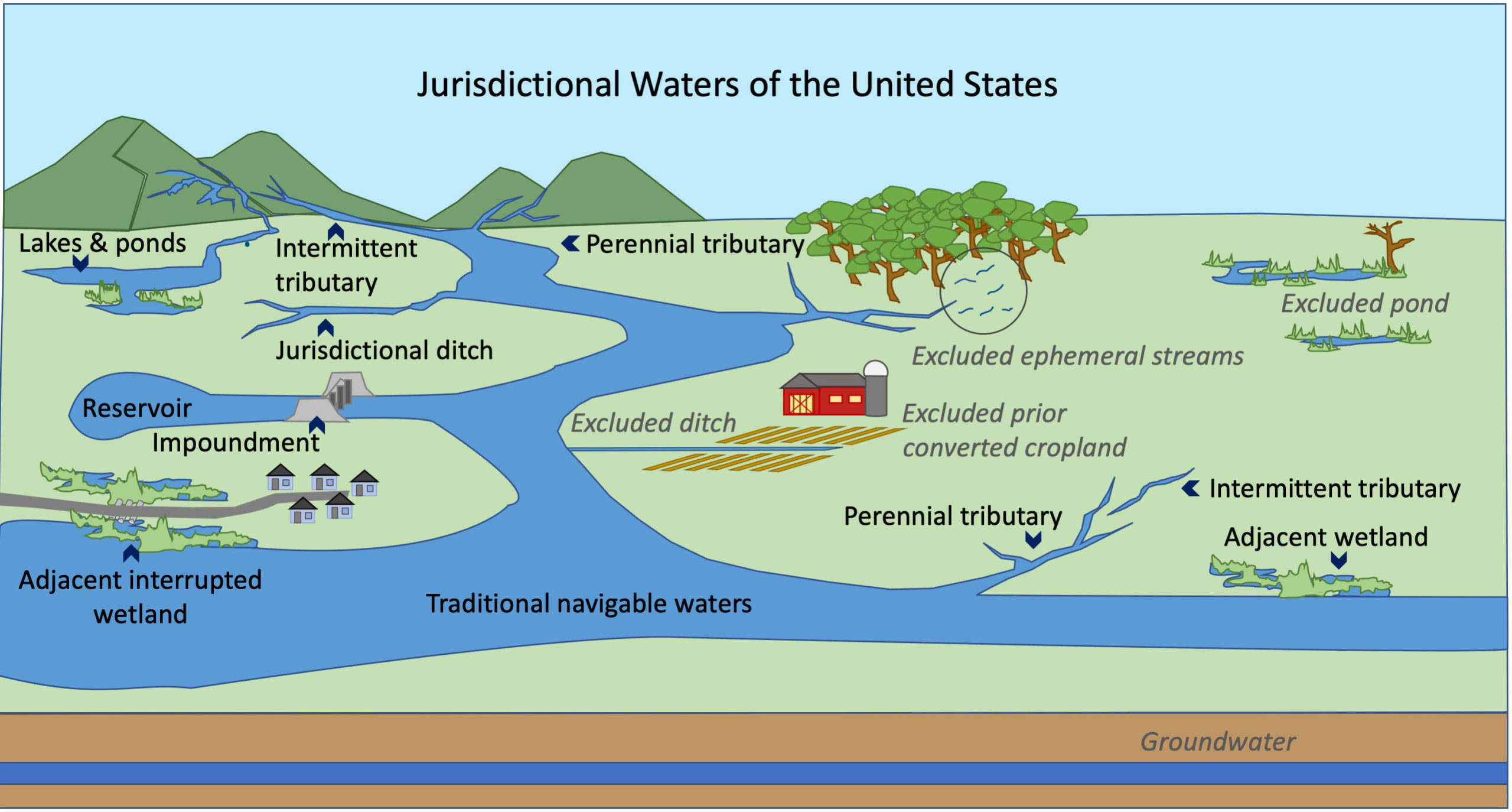

The 2015 Clean Water Rule, now the Navigable Waters Protection Rule, was amended in part because the definition of the Waters of the United States (WOTUS) within it was considered too broad. The definition of WOTUS in the Clean Water Rule gives the federal government jurisdiction over specific navigable waters (figure 1).WOTUS is a jurisdictional term used within the Clean Water Act; it pertains to wetland permitting, vessel sanitation devices, the national pollutant discharge elimination system, oil/hazardous spill prevention and control, and countermeasure regulations (sections 404, 312, 402, and 311 within the Clean Water Act, respectively).1 The WOTUS definition is integral to the Endangered Species Act, as previously regulated water bodies that support threatened and or endangered species may not remain regulated under the 2020 definition.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency and the United States Army Corps of Engineers (the agencies) co-drafted the definition of WOTUS included within the 2015 Clean Water Rule (2015 Rule). The final rule, published April 21, 2020 in the Federal Register, will be effective as of June 22, 2020.2 This article summarizes the recent history of the Clean Water Rule, including the 2020 Navigable Waters Protection Rule that fulfilled Executive Order 13788,3 amending the definition of WOTUS and providing clarity on the surface water bodies governed by the State versus Federal jurisdiction. The article also discusses how the new WOTUS definition impacts agricultural and specialty crop producers.

Figure 1. Jurisdictional Waters of the U.S. regulated under the 2020 Navigable Waters Protection Rule are listed in the black text. Waters excluded from regulatory control are listed in gray italicized text. Image credit: Sarah A. White, Clemson University. (Adapted from USEPA.)

Recent History of WOTUS

In the 2015 update to the Clean Water Rule, many new restrictions were put in place to prevent, reduce, and eliminate pollution. These restrictions broadened the definition of “navigable waters,” giving the federal government control over more surface waters, including those that only temporarily hold water. The term “navigable waters” granted the government control over waters even if no direct connection to more extensive waterways was apparent.

The 2019 Revised Regulatory Definition of WOTUS: The 2020 Rule

On April 21, 2020, the agencies published the Navigable Waters Protection Rule (2020 Rule), repealing the 2015 Rule and amending the definition of WOTUS as to reflect precedent set by decisions made by the Supreme Court.4

Per the 2020 Rule, WOTUS are defined as the following2:

- “All waters which are currently used, or were used in the past, or may be susceptible to use in interstate or foreign commerce, including all waters which are subject to the ebb and flow of the tide.”

- “All interstate waters including interstate wetlands” (interstate wetlands are wetlands that cross state lines).

- “All other waters such as intrastate lakes, rivers, streams (including intermittent streams), mudflats, sandflats, wetlands, sloughs, prairie potholes, wet meadows, playa lakes, or natural ponds, the use, degradation or destruction of which could affect interstate or foreign commerce including any such waters:

- Which are or could be used by interstate or foreign travelers for recreational or other purposes; or

- From which fish or shellfish are or could be taken and sold in interstate or foreign commerce; or

- Which are used or could be used for industrial purposes by industries in interstate commerce.”

- “All impoundments of waters otherwise defined” as WOTUS.

- “Tributaries of waters identified” in (1) through (4) above.

- “Territorial seas.”

- “Wetlands adjacent to waters (other than waters that are themselves wetlands) identified in” (1) through (6) above.

- “Waters of the United States do not include prior converted cropland. Notwithstanding the determination of an area’s status as prior converted cropland by any other Federal agency, for the purposes of the Clean Water Act, the final authority regarding Clean Water Act jurisdiction remains with E.P.A.”

Specific changes, as defined in the 2020 Rule, include organizing WOTUS into four categories:

- Territorial seas and traditional navigable waters: points 1 to 3 above – these include large rivers and lakes and tidally influenced waterbodies used in travel between states or for foreign commerce (e.g., Mississippi River, Chesapeake Bay, Erie Canal, Intercoastal Waterway).

- Certain lakes, ponds, and impoundments: point 4 above – lakes, ponds, and impoundments are considered navigable waters if they contribute surface water flow to navigable water or territorial sea either directly through other WOTUS or indirectly through channelized artificial or natural features (e.g., Lake Hartwell and the Savannah River).

- Perennial and intermittent tributaries to those waters: point 5 above – waters are contributing surface flow to traditional navigable waters. These waters must flow two times or more per year and be connected to navigable waters either directly or via channelized features, whether natural (e.g., boulder fields, debris piles) or artificial (e.g., ditches, spillways, and culverts). Ditches are tributaries if they (1) contribute flow to navigable water more than two times per year, (2) were constructed to relocate a tributary, or (3) were constructed in an adjacent wetland.

- Wetlands adjacent to jurisdictional waters: point 7 above – wetlands are “areas that are inundated or saturated by surface or groundwater” frequently enough to support the growth of vegetation adapted for life in saturated soil conditions.2 Wetlands include bogs, Carolina Bays, marshes, swamps, and similar areas. Adjacent wetlands are wetlands that

- physically touch jurisdictional waters

- are separated by a natural berm, bank, or dune

- are inundated by flooding from a WOTUS

- are separated by an artificial dike, barrier or “similar” artificial structure that allows direct hydrologic connection (e.g., culvert, flood or tide gate, pump, or similar artificial feature)

- is divided by a road or artificial structure that permits direct hydrologic surface connection through or over a structure in a typical year

Finally, the 2020 Rule more clearly defines bodies of water not included in WOTUS, which are

- groundwater (including groundwater that drains through subsurface drains in agricultural lands)

- ephemeral features (e.g., streams, swales, gullies, rills, and pools) that flow in response to precipitation

- diffuse stormwater runoff and sheet flow over uplands

- many roadside and farm ditches (non-navigable designation)

- prior converted cropland

- artificially irrigated areas (if irrigation ceases, the land would revert to upland characteristics)

- artificial lakes or ponds constructed in upland areas (e.g., water storage reservoirs and ponds used for agricultural purposes – irrigation or stock watering)

- stormwater control, retention, infiltration, and treatment structures in upland areas

- water-filled depressions in upland or non-jurisdictional water areas (e.g., mining or construction activities)

- groundwater recharge, water reuse, and wastewater recycling structures constructed in upland areas

- contained waste treatment systems – defined to include “all components, including lagoons and treatment ponds (such as settling or cooling ponds), designed to either convey or retain, concentrate, settle, reduce, or remove pollutants, either actively or passively, from wastewater or stormwater prior to discharge (or eliminating any such discharge).”2

One exception to the above bodies of water not included within WOTUS is abandoned, prior converted cropland (i.e., cropland not used for or in support of agricultural purposes for the preceding five years). If cropland is abandoned for five or more years and has reverted to a wetland, the wetlands within that cropland are regulated under the 2020 Rule.2

Groundwater and the Clean Water Act WOTUS Definition

Groundwater itself is not a jurisdictional WOTUS and is not regulated by the Clean Water Act; the 2020 Rule follows this long-established principle. However, the Supreme Court recently re-confirmed that the Clean Water Act does protect against the pollution of water that travels through groundwater from a point source – such as a buried pipe – when the discharge through groundwater is the functional equivalent of a direct discharge into a jurisdictional WOTUS.5,6 An example would be an unpermitted discharge of a chemical to a stream from a buried pipe not far from the stream. Agricultural and specialty crop producers should always think about how applied chemicals move through their farm’s soils and groundwater, and the proximity of the discharge of chemicals to WOTUS. It is best practice to follow label recommendations, practice integrated pest management, and consider weather conditions when timing chemical applications to limit the potential for agrichemical movement from/through production areas.

The Impact of the 2020 Ruling on Agricultural and Specialty Crop Stakeholders

Many agricultural and specialty crop stakeholders use ponds, wells, natural streams, and rivers for irrigation water sources. Well water is also used to fill some irrigation ponds. Water withdrawals for irrigation in South Carolina increased by 6.5% from 2017 to 2018 (5% increase from surface water, 7% increase from groundwater – the irrigation category also includes landscape irrigation).7,8 Water withdrawals will likely continue to increase because new irrigation systems are being continuously installed.

The 2020 Rule respects the rights of “States, localities, tribes, and private property owners” while protecting the environment and regulating the WOTUS.9 The 2020 Rule ensures that the agencies operate within Congress’ charge to protect navigable waters and identifies the waters federally protected under the Clean Water Act, Navigable Water Protection Rule. The 2020 Rule clearly defines the types of water bodies that are considered jurisdictional WOTUS. This distinction allows farmers to manage non-jurisdictional waters as they desire as long as they comply with all other laws related to water management (e.g., pesticide applications, reporting water usage).

If a farmer/producer is unsure if the Navigable Water Protection Rule regulates water bodies on their land, they should contact their regional Army Corps of Engineers office. Agencies can identify and classify the types of surface water features using various means, including site visits, remote sensing, maps, surveys, and hydrologic models.8 Agencies will then make WOTUS classification decisions based on the weight of evidence from the most reliable sources of information. If a water body on a producer’s land is determined to be a jurisdictional WOTUS, the producer should work with an agency representative to develop a management plan for their water source to comply with Federal rules.

Agricultural and specialty crop producers need to consider a few points, even with the revised WOTUS. The first is that the Endangered Species Act still protects wetlands that no longer classify as WOTUS (e.g., those that are completely hydrologically disconnected from other WOTUS) as they provide habitat for endangered species. Another point of consideration is managing the quality of water leaving their property. Contaminants (e.g., bacterial, nutrient, pesticide, or sediment) from agricultural sources are considered non-point source pollutants. Non-point source pollutants can potentially impair WOTUS either by overland flow (e.g., infrequent large rain events might connect excluded waters to WOTUS) or by seepage through soils to groundwater. Producers need to implement and manage best management practices so that contaminants do not leave their property. The Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQUIP) offered by NRCS offers producers assistance in identifying and planning conservation practices and financial aid for their implementation.

References Cited

- The Federal Water Pollution Control Act (The Clean Water Act). Ch. 26: Water pollution prevention and control: 33 U.S.C. §§1251-1387. 2019 [accessed 2020 Jun 16]. https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title33/chapter26&edition=prelim.

- The Navigable Waters Protection Rule: Definition of “Waters of the United States.” Federal Register 85 FR 22250. Vol. 85, No. 77. Department of the Army, Corps of Engineers, Department of Defense, and Environmental Protection Agency. 2020 [accessed on 2020 May 4]. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-04-21/pdf/2020-02500.pdf.

- Trump, D. Presidential Executive Order on Restoring the Rule of Law, Federalism, and Economic Growth by Reviewing the “Waters of the United States” Rule. 2017 [accessed on 2020 May 4]. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/03/03/2017-04353/restoring-the-rule-of-law-federalism-and-economic-growth-by-reviewing-the-waters-of-the-united.

- Overview of the Navigable Waters Protection Rule – Fact Sheet. E.P.A. Navigable Waters Protection Rule. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2020 [accessed 2020 May 4]. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2020-01/documents/nwpr_fact_sheet_-_overview.pdf].

- Supreme Court of the United States. Opinion of the Court: County of Maui, Hawaii v. Hawaii Wildlife Fund et al. 2020 [accessed 2020 June 11]. 18-260. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/19pdf/18-260_jifl.pdf.

- Supreme Court of the United States. Judgment of the Court: Kinder Morgan Energy Partners, LP v. Upstate Forever. 2020 [accessed 2020 June 11]. https://www.supremecourt.gov/search.aspx?filename=/docket/docketfiles/html/public/18-268.html.

- Monroe LA. South Carolina water use report 2017 summary. Columbia (South Carolina): South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control. 2018 [accessed 2020 June 11]. 0814-18. https://scdhec.gov/sites/default/files/media/document/Water%20Use%20Report%20Summary%202017.pdf.

- Monroe LA. South Carolina water use report 2018 summary. Columbia (South Carolina): South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control. 2019 [accessed 2020 June 11]. 0528-19. https://scdhec.gov/sites/default/files/media/document/South%20Carolina%20Water%20Use%20Report%202018%20Summary%20%281%29.pdf.

- Implementing the Navigable Waters Protection Rule -Fact Sheet. E.P.A. Navigable Waters Protection Rule. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2020 [accessed 2020 May 4]. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2020-01/documents/nwpr_fact_sheet_-_implementation_tools.pdf.