South Carolina Shellfish Industry Recovery: What Will it Take?

The South Carolina shellfish industry has suffered due to COVID-19 related restaurant closures.1 Now that restaurants have started reopening, producers are wondering how long the recovery may take. While there is no exact timeline, the recovery will depend on a few factors: a reduction in the unemployment rate, a restoration of household income, and a recovery of household restaurant expenditures to pre COVID-19 levels.

There may be opportunities for shellfish producers to switch sales channels from restaurants to other sales avenues, but there are significant obstacles. Hopefully, the industry and its supporters (policymakers, advocates, and consumers) can work together to overcome these obstacles and speed the recovery of South Carolina’s shellfish industry.

Shellfish Consumption and Restaurant Spending

This publication is part of a series covering South Carolina agricultural businesses that supply restaurants. A previous article, “The Post COVID-19 Restaurant Recovery May Take While”, examined the impact on restaurant businesses and how long it may take them to recover.2 The bad news is that it may take a while. Based on a US Department of Agriculture (USDA) study of restaurant spending after the Great Recession of 2007-2009,3 the recovery period took eleven years and mirrored employment recovery (restaurant spending recovered as unemployment dropped to pre-recession levels). The post-COVID-19 restaurant recovery may be quicker if employment recovers faster than it did after the Great Recession.

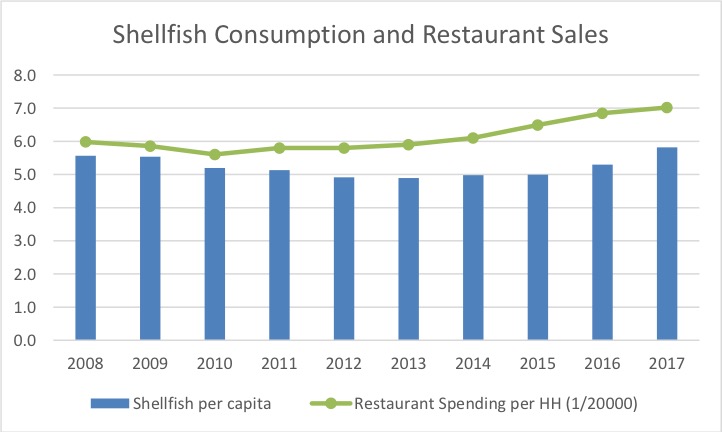

Shellfish consumption appears to follow the same recovery pattern when plotted against household restaurant spending (figure 1). This may simply reflect that shellfish sales are reliant on restaurant sales. However, it appears that shellfish consumption is affected by two additional variables: age and household income:

- A journal article in Nutrients found that US seafood consumption varied by age, income level, and education and not by race, gender, or ethnicity.4 Lower age and income levels were associated with lower seafood consumption.

- A University of Florida study showed that there was a significant negative association with seafood consumption for people under fifty years old and households with incomes below $74,999.5

The relationship between household income and restaurant spending is not surprising. More concerning is age. Older Americans are in a higher COVID-19 risk group, and this may make them more reluctant to return to restaurants. It will be interesting to find out if findings from a recent Clemson University survey of South Carolina seafood consumers shows similar results.6

Figure 1. Shellfish consumption per capita and household restaurant spending after the great recession. Image credit: Steve Richards, Clemson University.

Can Shellfish Producers Find Other Sales Opportunities?

Another article in this series, “Opportunities for Specialty Crop Producers During the COVID-19 Restaurant Recovery,” discussed coping strategies used by specialty crop producers, who are also highly dependent on restaurant sales.7 Many specialty crop producers were able to pivot from restaurant sales into other sales channels such as direct to consumer sales, online sales, and grocery store sales.

Shellfish producers, however, will have a harder time pivoting away from their restaurant sales channels due to some steep obstacles: licensing, processing, price, consumer education, data reporting, infrastructure, and industry promotion.

Licensing

Seafood is highly regulated. The US Food and Drug Administration has guidelines producers must follow, and numerous licenses are needed from at least two different South Carolina agencies: the Department of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC) and the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR). Graham Gaines, with the South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium, is currently working on a guide to help producers through this legal maze. His contact information is at the end of this article.

Processing

There are very few seafood processors left in South Carolina. Consolidation in the processing and distribution of seafood is similar to that of the beef or pork industry. Small scale seafood processing is virtually non-existent and limits direct to consumer sales. For instance, restaurants know how to prepare fresh seafood: they know how to peel and devein shrimp, how to shuck oysters, how to pick crab meat, and how to steam clams. Most customers are less willing and less adept at doing these preparations.

This shows up as a convenience issue in seafood preference surveys with the three of the most commonly cited barriers to consumption being: “lack of preparation knowledge,” “too time consuming to prepare,” and “product safety concerns (oysters)”.5 In addition, the recent Clemson University survey documented that South Carolinians bought their seafood pre-cooked 56% of the time.6

Price

As discussed previously, household income plays a role in the likelihood a person consumes seafood. This means price will limit consumer sales to a certain segment of the population. The University of Florida study found that price was the top reason for not consuming shrimp or oysters.5 And, cost was considered as “important” or “very important” by 83% of respondents in the recent Clemson University survey.6 These price concerns may be mitigated if producers address the other barriers on this list.

Consumer Education

Customers like seeing the shrimp boats while they eat at coastal South Carolina restaurants. It gives them a sense that they are eating local shrimp. This is likely not the case. The shucked and breaded clams and oysters were probably not processed in South Carolina either. Only 14% of those surveyed in the Clemson University study thought that their seafood came from international sources. Whereas the data show international seafood imports comprise between 65%8 and 80%9 of all US consumption. Shrimp comprise the highest volume of imports, at 81% of US consumption.10

Data Reporting

Educating consumers is a significant undertaking, made more difficult by a lack of information about where seafood is caught and where it is distributed after it is landed (docked and unloaded). The South Carolina seafood industry is much larger than what the landing statistics represent. This is due to three reasons. First, if a commercial fishing boat lands their catch in another state, the catch is recorded as that state’s catch, even if the fishing vessel hailed from South Carolina. Second, if a fishery has four harvesters or less, then the data is not reported (for fear of revealing trade secrets). And third, once the catch is landed, there is almost no tracking to find out where it is ultimately distributed and consumed.

The unfortunate part of this equation is that the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act relief funds are based on commercial landings of each state as a proportion of the national catch. As a result, South Carolina ranks near the bottom of the list for allocated relief funds.

Infrastructure

So, why are South Carolina fishing vessels landing their catch elsewhere? A lack of waterfront infrastructure: cold storage, processing, and distribution facilities. A fishing boat that is 200 miles out on the Atlantic Ocean has a choice where to land their catch. And, with all things being equal, the catch will be landed where there are waterfront facilities.

The disappearance of working waterfronts in South Carolina is due to the opportunity cost of being located on the water. Real estate developers, restaurants, and townships all realized there was more money to be gained through hotels, restaurants, and tourism than commercial fishing boats. Once a waterfront is lost to development, the infrastructure for commercial fishing is very difficult to rebuild.

To learn more about this issue, visit the working waterfronts page on the South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium website to understand how the Consortium is working with localities to preserve their working waterfronts.

Industry-Wide Promotion

Finally, all South Carolina seafood producers, policymakers, and consumers are going to need to work together to address issues with South Carolina seafood promotion. If producers can get organized and speak with one voice, they will have a better shot at getting more attention in Washington, DC, similar to the support the US beef and pork industries enjoy.11

Speaking with one voice is a challenge for an industry that has historically viewed each harvester and producer on a per-species basis: Oyster growers, oyster harvesters, clam growers, clam diggers, shrimpers, charter fishing, commercial fishing, crabbers, etc. This fragmentation has led to the chronic underfunding of promotional efforts on a local, state, and national level. Many of the professional and trade organizations have lost membership, are working with shrinking budgets, and/or have become completely inactive.12

Additional Assistance for Shellfish Producers on Its Way?

There are have been some successful efforts presenting the needs of the fishing and aquaculture industries to congress. Two recent developments:

- The National Fisherman online magazine reports that fishermen and aquaculture producers are asking congress for $1.5 billion to bolster local seafood supply chains.13 A coalition of 238 organizations signed a letter requesting more effort connecting and promoting producers, suppliers, and consumers of locally sourced seafood.

- On May 7, 2020, President Trump signed an Executive Order on “Promoting American Seafood Competitiveness and Economic Growth”.14 This order specifies that unnecessary regulatory barriers be removed (both to fishing and aquaculture), promoting industry transparency and data collection, creating an aquaculture strategic plan and opportunity zones, and leveling the food safety playing field between domestic and imported seafood.

South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium

The South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium partners with Clemson University and will take the lead on efforts to promote South Carolina’s seafood industry, to assist working waterfronts, and to provide technical assistance to aquaculture and fishing businesses. Graham Gaines, South Carolina Sea Grant’s living marine resources specialist, is the contact for questions concerning aquaculture production and commercial fishing. He works with seafood producers and seafood communities to develop more sustainable and efficient operations.

Graham Gaines, graham.gaines@scseagrant.org

(843) 470-5109

Beaufort County Clemson Cooperative Extension Building

18 John Galt Road, Beaufort, South Carolina

The main office number for the South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium is (843) 953-2078, and a staff directory and resources for marine fisheries, aquaculture, and working waterfronts are located on the South Carolina website.

Clemson Extension Agribusiness Program Team Resources

Steven Richards, Agribusiness Associate, with the Clemson Agribusiness Program Team, is an experienced agribusiness professional and is available to take questions and provide information about agricultural business and industry topics, including management, marketing, and finances, especially those related to the impact of COVID-19 on agribusinesses.

Steven Richards, Agribusiness Associate

P (843) 473-602

M (315) 573-8632

18 John Galt Road, Beaufort, South Carolina.

Additional Agribusiness Program Team member contact information and COVID-19 resources are available on the Clemson Extension Agribusiness Program Team website.

Specific resources for specialty crop farmers looking to open new sales channels are available on the Marketing page of the website.

References Cited

-

- Richards S. Impacts of COVID-19 restaurant closures on South Carolina’s shellfish industry. Clemson (SC): Clemson Cooperative Extension, Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension; 2020 Jun 17. LGP 1070. http://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/impacts-of-covid-19-restaurant-closures-on-south-carolinas-shellfish-industry/.

- Richards S. The post-COVID-19 restaurant recovery may take a while. Clemson (SC): Clemson Cooperative Extension, Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension; 2020 Jun 10. LGP 1068. http://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/the-post-covid-19-restaurant-recovery-may-take-a-while/.

- Cho C, Todd JE, Saksena M. Food spending of middle-class households hardest hit by the great recession. a special report from America’s eating habits: food away from home. Washington (DC): US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2018 Sept 27 [accessed 2020 Sep 18]. EIB-196. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/90228/eib-196.pdf.

- Jahns L, Raatz SK, Johnson LK, Kranz S, Silverstein JT, Picklo M (Sr). Intake of Seafood in the US Varies by Age, Income, and Education Level but Not by Race-Ethnicity. Nutrients. 2014 Dec;6(12):6060-75. doi:10.3390/nu6126060.

- Xumin Z, House L, Sureshwaran S, Hanson T. At-home and away-from-home consumption of seafood in the United States. University of Florida, 2004. https://ideas.repec.org/p/ags/saeaft/34738.html.

- Cheplick, D, Motallebi M, Dickes L, Richards S, Walters K, Whetstone J, Robinson K, Carey R. South Carolina aquaculture futures consumer survey summary statistics. Clemson University. 2020 May [accessed 2020 May]. (Unpublished Report for USDA NIFA Grant Award No. 2019-67024-29671).

- Richards S. Opportunities for Specialty Crop Producers During COVID-19 Restaurant Recovery. Clemson (SC): Clemson Cooperative Extension, Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension; 2020. LGP 1067. http://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/opportunities-for-specialty-crop-producers-during-covid-19-restaurant-recovery/.

- Mossler M. How much U.S. seafood is imported? Pullman (WA): Sustainable Fisheries. [accessed 2020 Jun 4]. https://sustainablefisheries-uw.org/fact-check/how-much-seafood-is-imported/.

- Fishwatch U.S. Seafood Facts. [accessed 2020 Jun 4]. https://www.fishwatch.gov/sustainable-seafood/the-global-picture.

- Seafood Health Facts. Making smart choices balancing the benefits and risks of seafood consumption: balancing the benefits and risks of seafood consumption. Lewes (DE): Delaware Sea Grant. National Aquaculture Extension Initiative of the National Sea Grant Program; 2020. https://www.seafoodhealthfacts.org/

- Crampton L. US seafood sales have dipped as much as 95%, and processors have had to scale back operations and lay off staff. PoliticoPro Intelligence. 2020 May 26 [accessed 2020 May 21]. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/05/26/seafood-industrys-fragmentation-makes-recovery-harder-281861.

- Graham Gaines, South Carolina Sea Grant Living Marine Specialist. Written comments while reviewing an earlier version of this paper.

- Moore K. Seafood businesses call for $1.5 billion federal COVID-19 Aid. Portland (ME): The National Fisherman; 2020 May 5 [accessed 2020 May 5]. https://www.nationalfisherman.com/national-international/fishermen-seafood-businesses-call-for-1-5-billion-federal-covid-19-aid.

- The White House. Presidential Executive Order. Promoting American seafood competitiveness and economic growth. Signed by President Donald Trump on May 7, 2020. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/05/12/2020-10315/promoting-american-seafood-competitiveness-and-economic-growth.