The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent restaurant closures had a significant impact on many agricultural businesses in South Carolina. One of the most impacted was the seafood industry. While the exact magnitude of the impact is difficult to calculate, there is some evidence indicating that the shellfish industry was particularly hard hit. Data such as shellfish consumption trends, the amount of shellfish consumed in restaurants, and harvest seasons tell part of the story. Anecdotal evidence from producers themselves also suggests the extent of the impact. While there are funds available to mitigate some of this damage through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, it is not going to be enough.

South Carolina’s Seafood Industry

South Carolina’s seafood industry is important to the state’s economy. The most recent statistics from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Department of National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) show that South Carolina’s seafood industry has an economic impact of 1,209 jobs, contributing $39.3 million to South Carolina’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).1

Shellfish are a particularly important piece of South Carolina’s seafood industry, namely shrimp, crabs, clams, and oysters. The shrimp and crabs are wild-caught, and the clams and oysters are both farm-raised (in aquaculture operations) and wild-harvested.

Seafood and Shellfish Consumption is Rising

Per capita, seafood consumption has increased from 14.9 pounds per person in 2011 to 16.1 pounds in 2017.2 Fresh and frozen seafood accounts for most consumption (79%), with the remaining being consumed as canned or cured (smoked, pickled, etc.) seafood.3

In the US, almost half of all fresh and frozen seafood consumed is shellfish (versus finfish), with shrimp consumed at 4.4 pounds per person, followed by 0.54 pounds of crab meat, 0.34 pounds of clam meat, and 0.18 pounds of oyster meat.2 Consumption of shellfish in South Carolina is generally the same as that for the United States, except oysters are consumed at a higher rate than clams.4

Most Local Shellfish is Consumed in Restaurants

Statistics vary on how much seafood is consumed in restaurants. For all seafood, the reported range is between 25%5 and 46%.6 A recent Clemson University survey of South Carolina seafood consumers puts this number right in the middle, at 36%.4 However, these studies measure all seafood (finfish and shellfish) from all sources (domestic and imported). This percentage is skewed by grocery purchases of canned tuna and pre-cooked frozen imported shrimp. Fresh and frozen local seafood (whether wild-caught or farmed) is much more concentrated in restaurant channels.

Restaurant consumption can vary by the type of seafood as well, with shellfish consumption occurring more frequently. For instance, one study estimates that 58% of shrimp and 62% of oysters are consumed at restaurants.6 An aquaculture feasibility study conducted in the Lowcountry estimates restaurant consumption of single, premium oysters “on the half-shell” at 90%.7

This indicates that South Carolina’s seafood harvesters and aquaculture producers are heavily reliant on restaurant businesses purchasing their products. If an estimate were to be made, South Carolina restaurants probably buy at least 65% to 75% of locally sourced shellfish. Some support for this estimate comes from recent news stories covering the fishing industry:

- “US Seafood Sales Have Dipped as Much as 95% and Processors Have Had to Scale Back Operations and Lay Off Staff” (Politico Pro, 2020).8 The article blames the 95% drop in seafood sales on restaurant closures.

- “Americans Are Cooking More Seafood, but Fisherman Are Struggling” (Wall Street Journal, 2020) The article estimates seafood consumption in restaurants between 70% to 80%, depending on the business interviewed.9

- Two-thirds or more (at least 66%) of seafood is consumed at restaurants, according to Alaskan Seafood Marketing Institute Executive Director, Jeremy Woodrow (Marketplace News, 2020).10

Impact of COVID-19 Restaurant Closures on the South Carolina Shellfish Industry

When restaurants shut down, the general reaction of South Carolina’s shellfish industry was to stop harvesting and wait out the COVID-19 storm. The result was that South Carolina shellfish producers lost at least two months of sales. To reduce losses, wild-caught shellfish harvesters cut expenses by not taking their boats out. Aquaculture producers, however, had to maintain operations and may not have been able to reduce expenses as much as the harvesters.

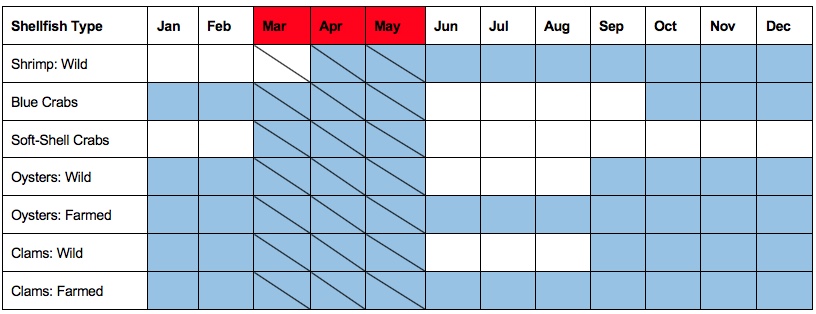

The timing of fishing seasons and the closure of restaurants due to COVID-19 affected each shellfish species differently (table 1). Some seasons were cut short, some had a delayed start, and some were eclipsed entirely.11

Table 1. 2019-2020 fishing and harvest seasons by species and COVID-19 shutdown period. The shaded portions of the table represent the typical harvest seasons, and the crossed-out cells are the months affected by COVID-19 restaurant closures. Crab season is open year-round, so the shaded cells on the chart reflect the best times to catch crab.

Wild Caught Shrimp

Shrimp fishing season in provisional waters opened early, on April 15, 2020, and South Carolina waters were opened on May 27, 2020. Some shrimpers took advantage of this early season opening to sell their shrimp directly to consumers. However, the volume of direct sales did not make up for the lost restaurant sales, and some shrimpers did not launch their boats until after restaurants re-opened.

Blue Crabs and Soft-Shell Crabs

Blue Crab harvesting was nearing the end of the preferred fishing season (generally May 15), and harvesters stopped or reduced the blue crab catch earlier than normal. Soft-shell crab season, however, was completely eclipsed by the COVID-19 restaurant shutdown, reducing sales by as much as 75%. Soft-shell crab producers (those that keep blue crabs in tanks under observation until they molt/shed their shell) reduced the number of crabs they purchased from crab harvesters and began freezing as many soft-shelled crabs as possible.

Wild Harvested Oysters and Clams

Wild harvested oysters and clams had their end-of-harvest season sales clipped by restaurant closures. Harvesters basically lost two months of revenue, as their season ended on May 31, 2020. Cancellations of public and private oyster roasts may have impacted the wild oyster harvesters even more than restaurant closures.11

Oyster and Clam Aquaculture

Aquaculture farms were just ramping up for the tourist season surge in sales when COVID-19 closures hit. These producers harvest every month of the year, so they try to match their harvest volumes with anticipated restaurant demand. The two months of restaurant closures gave these producers little choice other than to lay off staff and delay harvesting. However, this has resulted in larger-than-desired shellfish that may be harder to sell.

Seafood Relief Funds in CARES Act

On May 7, 2020, the US Secretary of Commerce announced that there would be $300 million in aid to fisheries and the seafood sector through the CARES Act. South Carolina will receive $1,525,636 for its seafood industry, which is likely insufficient to cover the losses experienced. Press announcements are expected soon. General details are listed below12:

- How the funds will be disbursed is still being determined by the Atlantic State Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC), NOAA, and the SC Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR). Each state may have slightly different allocation guidelines.

- Eligible businesses include commercial fishing businesses, charter fishing businesses, qualified aquaculture operations, seafood processors, and seafood dealers.

- Ineligible businesses include vessel repair businesses, bait and tackle suppliers, seafood restaurants, and seafood retailers.

- Economic losses will need to meet a threshold of 35%, as compared to the businesses’ prior five-year average.

- SCDNR is developing a spending plan, on which they will request feedback from the public before submitting to NOAA for approval.

- SCDNR will be handling applications and evaluations, while ASMFC will disburse the checks.

South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium

The South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium partners with Clemson University and will take the lead on efforts to promote South Carolina’s seafood industry, to assist working waterfronts, and to provide technical assistance to aquaculture and fishing businesses. Graham Gaines is the contact for questions concerning aquaculture production and commercial fishing. He works with seafood producers and seafood communities to develop more sustainable and efficient operations.

Graham Gaines, graham.gaines@scseagrant.org

(843) 470-5109

Beaufort County Clemson Cooperative Extension Building

18 John Galt Road, Beaufort, South Carolina

The main office number for the South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium is (843) 953-2078, and a staff directory and resources for marine fisheries, aquaculture, and working waterfronts are located on the South Carolina website.

Clemson Extension Agribusiness Program Team Resources

Steven Richards, Agribusiness Associate, with the Clemson Agribusiness Program Team, is an experienced agribusiness professional and is available to take questions and provide information about agricultural business and industry topics, including management, marketing, and finances, especially those related to the impact of COVID-19 on agribusinesses.

Steve Richards, MBA, stricha@clemson.edu

P (843) 473-6024

M (315) 573-8632

Beaufort County Clemson Cooperative Extension Building

18 John Galt Road, Beaufort, South Carolina

Additional Agribusiness Program Team member contact information and COVID-19 resources are available on the Clemson Extension Agribusiness Program Team website.

Specific resources for specialty crop farmers looking to open new sales channels are available on the Marketing page of the website.

Additional COVID-Related Publications for Agribusinesses

Richards S. The post covid-19 restaurant recovery may take a while. Clemson (SC): Clemson Cooperative Extension, Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension; 2020. LGP 1068. http://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/the-post-covid-19-restaurant-recovery-may-take-a-while/.

References Cited

- NOAA Fisheries. Fisheries Economics of the United States, 2016. US Dept. of Commerce. Silver Spring (MD): National Marine Fisheries Service; 2018 Dec 12. NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-F/SPO-187; p. 243. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/resource/document/fisheries-economics-united-states-report-2016.

- USDA Economic Research Service. Food availability (per capita) data system: fish and shellfish per capital consumption. 2019. [accessed 2020 Jun 1]. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-availability-per-capita-data-system/.

- NOAA Fisheries of the United States, 2017. 2017 US commercial fisheries and seafood industry, how our catch is used. 2017. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/fisheries-united-states-2017.

- Cheplick, D, Motallebi M, Dickes L, Richards S, Walters K, Whetstone J, Robinson K, Carey R. South Carolina aquaculture futures consumer survey summary statistics. Clemson University. 2020 May [accessed 2020 May]. (Unpublished Report for USDA NIFA Grant Award No. 2019-67024-29671).

- Changes in Seafood Consumption. Norwegian Seafood Council. [updated 2019 Jun 28; accessed 2020 Jun 28] https://en.seafood.no/market-insight/other-content/fish-market/fish-market2/changes-in-seafood-consumption/.

- Xumin Z, House L, Sureshwaran S, Hanson T. At-home and away-from-home consumption of seafood in the United States. University of Florida, 2004. https://ideas.repec.org/p/ags/saeaft/34738.html.

- Richards S. Feasibility study: Lowcountry oyster production. South Carolina business level feasibility study. Clemson University. [accessed 2020 Feb 17]. (Unpublished; on file with USDA Rural Development).

- Crampton L. US seafood sales have dipped as much as 95%, and processors have had to scale back operations and lay off staff. PoliticoPro Intelligence. 2020 May 26 [accessed 2020 May 21]. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/05/26/seafood-industrys-fragmentation-makes-recovery-harder-281861.

- Newman J, Wernau J. Americans are cooking more seafood, but fisherman are struggling. The Wall Street Journal. 2020 May 21 [accessed 2020 May 21]. https://www.wsj.com/articles/americans-are-cooking-more-seafood-but-fishermen-are-struggling-11590062400.

- Southard L. Can American seafood survive the COVID-19 tidal wave? Marketplace News. 2020 May 6 [accessed 2020 May 6]. https://www.marketplace.org/2020/05/06/covid-19-amerian-seafood-commercial-fishing-industry/.

- Gaines G. South Carolina Sea Grant Living Marine Specialist. Written comments while reviewing an earlier version of this paper. [accessed 2020 Jun 5].

- Commerce Secretary Announces $300 Million in CARES Act Funding. NOAA Fisheries Office of Communications. 2020 May 7 [accessed 2020 May 8]. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/commerce-secretary-announces-allocation-300-million-cares-act-funding.