This article provides superintendents, golf course designers, landscapers, and groundkeepers with an understanding of common South Carolina native plants and considerations for incorporating native plants into out-of-play areas of a golf course. The information, figures, and charts included can be used as a guide to determine which plants are native to a select region and plants that are best suited for the golf course based on the plant’s characteristics, growing requirements, and size.

Introduction

As urbanization increases, there is less habitat, which influences the biodiversity and stability of natural ecosystems. The loss of natural vegetation and replacement with non-native plants or impervious surfaces can have detrimental impacts on the environment, including:

- Impervious surfaces can result in stormwater runoff as water can no longer infiltrate the ground.1 As a result, streams may become flashier (flow within a stream increasing or decreasing rapidly during a storm event) and potentially lead to increased contaminants in waterways. When plants are removed and replaced with impervious surfaces, the natural filtration provided by plants and soil is also removed. Pollutants and sediment are carried with runoff and deposited into waterways.

- Non-native plants may be less suitable habitats for wildlife. Non-native plants support a less diverse native insect population compared to native plants. Having a diverse and abundant insect population is critical because insects are near the bottom of the food chain and serve as a food source for consumers higher on the food chain.2 Native plants are important for pollinators whose life cycles are intimately tied to the life cycle (phenology) of native plants.

- Non-native plants risk becoming invasive. Natural predators are most likely missing when a non-native plant is brought into a new environment, such as a golf course.3 Therefore, the non-native plant has a competitive advantage and may out-compete native plants for resources. Similarly, native plants cultivated out of their endemic range can also become invasive (for example, groundsel tree [Baccharis hamilifolia] and cattail [Typha latifolia L.]). Thus, it is important to use native plants where they are known to occur naturally.

- Non-native plants also pose the risk of introducing new pathogens and diseases to the environment. In the past, the introduction of new pests, pathogens, and diseases has caused detrimental effects on the environment, reduced grassland bird species,4 and even eliminated entire native species.5

Increasing the use of native plants provides many local and ecosystem benefits, including

- Increasing water infiltration as water can absorb into the soil. Increased water infiltration along with foliage interception of water helps to decrease stormwater runoff volumes, soil erosion, and sedimentation.6

- Using native plants also helps to improve and increase water quality. Native plants require fewer inputs compared to non-native plants when utilized in their endemic environments.2 Reduced inputs are possible because native plants are adapted to the climate, rainfall, and soil type present in the area and, therefore, do not require as many amendments as non-native plants. This decreased usage or elimination of chemicals reduces the probability of chemicals entering and contaminating waterways.7 Once again, the native species selected need to be within their natural range and environmental characteristics. Think of the commonly used slogan: “Proper plant for the proper place.” Having said that, it is important to address the common mindset of growing and maintaining ornamentals. Generally, the thought is to fertilize and water plants, regardless of plant needs. With native plants, this approach is excessive and strategic applications of water when plants are establishing are desirable; otherwise, native plants in the right location require little to no additional resources.

- Native vegetation provides habitat for beneficial insects, pollinators, birds, and soil organisms, thus increasing biodiversity.8 For example, prairie plants provide nesting habitats for birds, such as quail.8

- Many beneficial insects and birds may help control golf course pests. For example, specific flowering plants attract parasitic and predatory insects that prey on pests, such as mole crickets and white grubs.9

- Native vegetation can add to the aesthetic of the golf course (dependent on membership and board goals and preferences) and be used as a model to teach the public about native plants.

Incorporating native plants into out-of-play areas can be accomplished at different scales in the golf industry. Small plantings may provide more minor wildlife benefits, while larger areas may act as islands of refuge in the overall urban environment. These green spaces are known to be essential for:

- Increasing connectivity between habitats10

- Providing refugia for many species, helping to support biodiversity2,10

- Aiding in stormwater management11

- Enhancing air quality12

- Helping reduce the heat island effect13

Out-of-Play Areas on Golf Courses

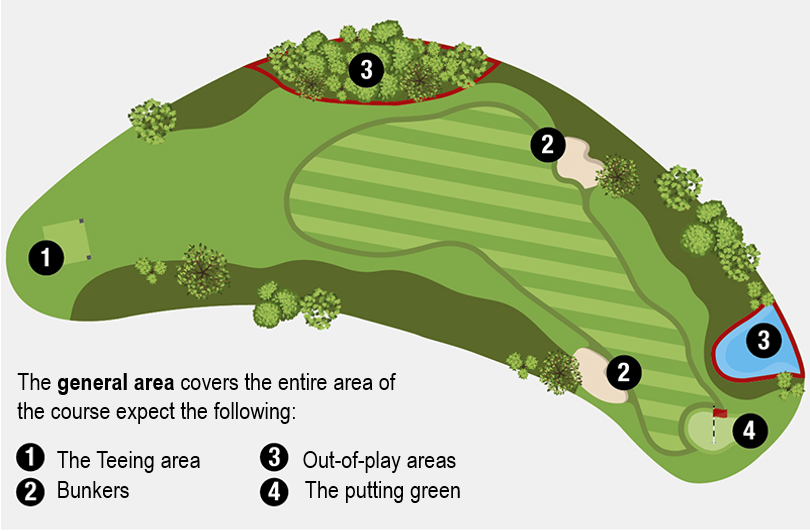

Out-of-play areas are outside the designated playing area where golfers are not allowed to play. These areas are also known as penalty areas, no play zones, and out of bounds.14 Out-of-play regions are marked with a white stake so golfers can identify where in the course their ball lands. Out-of-play areas can be composed of vegetation, bodies of water, and other materials, such as pine straw.14 Figure 1 illustrates areas of a golf course, including out-of-play areas. Out-of-play areas can have different functions.13 For example, vegetation around ponds and other bodies of water can help serve as a buffer and reduce fertilizer and pesticide runoff.

Figure 1. Areas of a golf course with the out-of-play areas (penalty areas) represented by #3. Adapted from USGA.org.

Golf courses offer a variety of ways to use native plantings and increase ecosystem services. Smaller native plantings adjacent to buildings and cart trails are suitable for attracting pollinators and offer food and shelter for smaller wildlife. Larger areas (such as ponds, wetlands, hardwood forests, and planted pinelands) can provide habitat for larger wildlife and greater ecosystem services such as stormwater management, water infiltration, and water purification.15

Native Ecosystems of South Carolina

Identifying what ecosystems and environments are native to South Carolina is difficult, as humans have been altering the environment for thousands of years. However, numerous plant communities have been identified as native through historical data and literature. For example, the riverine forest and longleaf pine are known ecosystems that used to occupy areas in South Carolina around river systems and the Coastal Plain region. Likewise, hardwood forests are native to the regions surrounding river terraces in South Carolina. Early settlers identified habitats such as prairies as occupying parts of South Carolina. However, the extent of prairies in pre-settlement South Carolina is unknown.5

Natural grasslands, prairies, and forest environments that used to occupy parts of South Carolina were home to native plant species that are no longer commonly seen. Native prairies, grasslands, wetlands, and pinelands are easy to integrate into larger out-of-play areas of golf courses. During the construction and development process, soils are removed, redistributed, compacted, and regraded. The outcome of the construction and developing process has changed environments, ecosystems, natural water flow patterns, soils, and seed banks throughout the state.5 For example, while mineral soils rich with organic matter (Mollisols) used to be common in Piedmont Prairie ecosystems and coastal grasslands of South Carolina, their conversion into farmlands has depleted the soil organic matter changing the composition of the soil. Today, Mollisols only represent one percent of South Carolina’s soils.16

Specific Benefits to Golf Courses

Incorporating native vegetation into golf courses offers specific economic benefits for the course that are mostly related to reduced inputs beyond the establishment period8:

- Native plants often reduce irrigation requirements, resulting in less water use. When water use is decreased, less money is required for operating and maintaining an irrigation system. By reducing plant irrigation demand during periods of drought, golf courses can better manage water volume used to ensure water withdrawals are not over their permitted limit.

- Native grasses and plants often require fewer chemical applications. When fewer fertilizer and pesticide applications are needed, product purchase costs, equipment maintenance, and labor for application are reduced.

- Native grasses and plants require less maintenance. Depending on the type of plants used in the landscape, mowing or trimming plants once per year can be beneficial. Limited to no mowing of these areas throughout the remainder of the year results in less money spent on gas, mower maintenance, and labor. However, some ecosystems prefer to be burned with a specific frequency.17 The burning of an ecosystem can offer benefits such as providing nourishment to the soil, clearing dead organic matter, and exposing the ground to sunlight. Although not all the same benefits occur as burning, mowing may mimic some of the natural processes that occur with burning.18 Mowing, like burning, helps to return nutrition to the soil and leads to higher biomass production.

- Natural areas and native plants are aesthetically pleasing to the golfer. Beyond the other traditional factors of course difficulty and costs, aesthetics can be an additional reason golfers select a course to play.

Considerations in Identifying Native Plants for a Specific Area

“Right place, right plant” is an important concept when identifying which plants to utilize in a landscape. This phrase refers to considering the plant’s endemic range and conditions in which it would naturally be found. For example, the soil type, landscape position (e.g., on a slope, upland, or wetland), and climate. Placing a native plant in the correct landscape position allows the plant to be positioned so that it can receive the proper light and drainage requirements. A sub-canopy tree that requires filtered light should not be placed in the open receiving direct sunlight. For example, the Carolina silverbell (Halesia carolina L.) is a sub-canopy tree that naturally grows in shaded environments.19 Therefore, the Carolina silverbell should not be planted as a canopy tree, exposed to full sun. A plant that requires well-drained soils should not be placed at the bottom of a slope, where water accumulates after a rainfall event. Every growing requirement and condition should be met for the native plant to thrive.

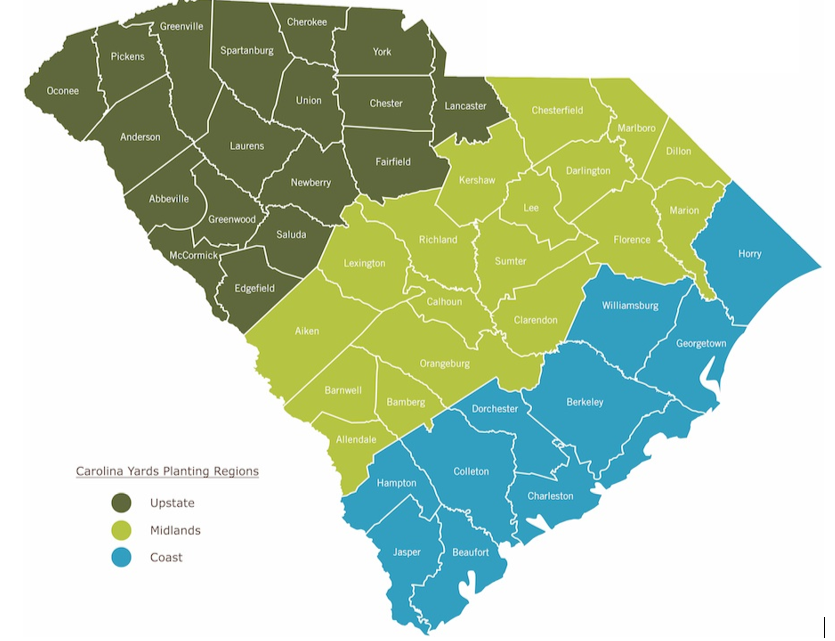

This publication uses the planting regions of South Carolina described by the Carolina Yards Program (figure 2) as guides for planting recommendations. The planting regions of South Carolina include the upstate, midlands, and coastal regions.

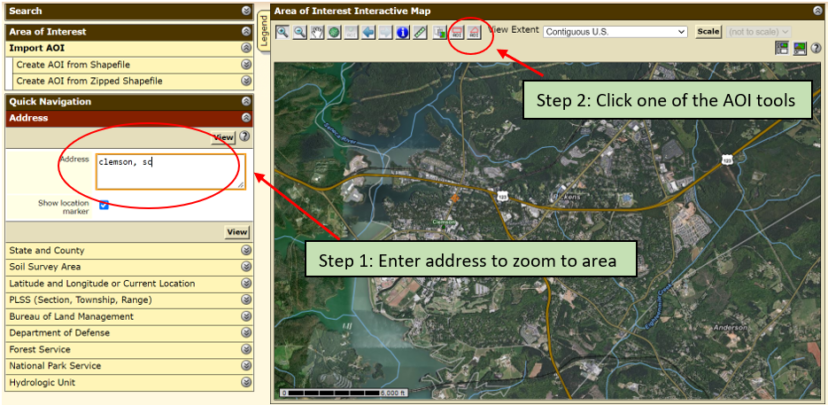

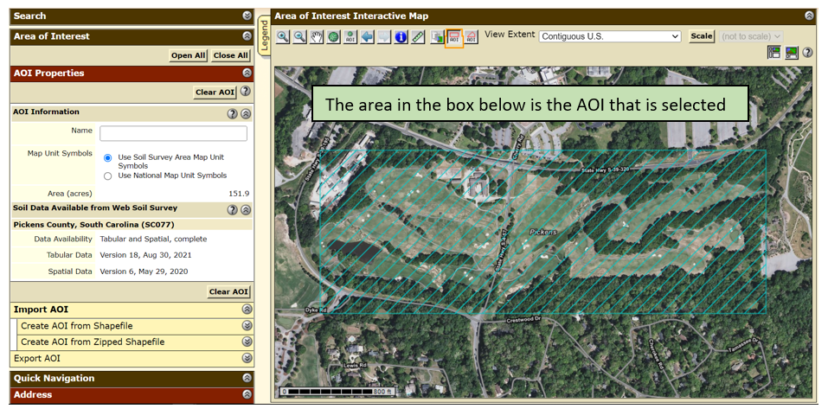

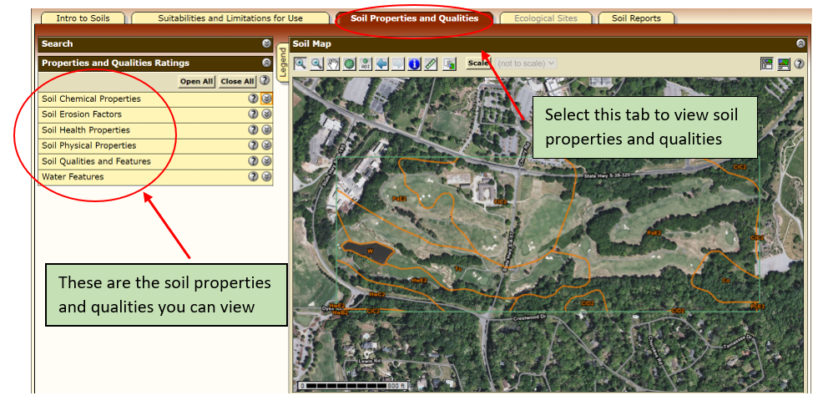

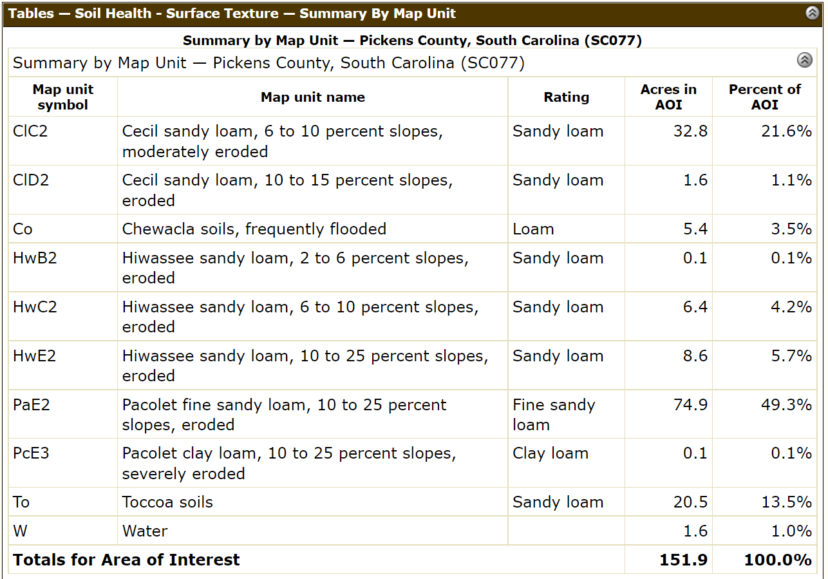

First, identify the planting region of the golf course by locating its county in figure 2. Next, survey the area where the native plants are to be used. Start by viewing information about the area on the Web Soil Survey website, websoilsurvey.sc.egov.usda.gov, provided by the National Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) of the US Department of Agriculture (USDA). To do so, navigate to the Web Soil Survey and click the green button that reads “Start WSS” at the top of the page. Then an area of interest (AOI) needs to be selected, which can be done in a few ways. One way is to navigate the map using the mouse to find the AOI. Alternative AOI selection methods include entering an address, state and county information, longitude and latitude coordinates, or using a current location. Once the AOI is pulled up on the map view, click the tool at the top of the map that reads “AOI” and draw a rectangle around the AOI (figure 3). Doing so will select the AOI (figure 4). Once the AOI is selected, navigate to the “Soil Map” tab, and click on the map unit name to view information such as slope, soil texture, composition, etc. On this webpage, other information regarding soil properties and quantities, suitability and limitations for use, soil reports, and ecological sites are available under the “Soil Data Explorer” tab (figure 5). Not all data is available for all areas. Another way to get information about the soil is to take a soil sample and send it to an agricultural lab for analysis. The Clemson University Agricultural Services Laboratory website provides guidance on how to submit soil samples to their lab. A basic soil test will include information on soil pH and buffer pH. Knowing the soil and buffer pH is important as soil pH adjustments may be beneficial in helping to establish plants.

Figure 3. Selecting AOI on the Web Soil Survey website. Image credit: screenshot by Payton Davis, Clemson University.

Figure 4. AOI selection on the Web Soil Survey website. Image credit: screenshot by Payton Davis, Clemson University.

Figure 5. Soil properties and qualities tab on the Web Soil Survey website. Image credit: screenshot by Payton Davis, Clemson University.

Figure 6. Example of soil texture output from the Web Soil Survey website’s soil property and qualities tab. Image credit: screenshot by Payton Davis, Clemson University.

In completing the land survey, it is important to identify

- Planting area: Determine how large an area is to be planted. Planting area size will help determine if you will target a few different species or a whole plant community.

- Sun or shade patterns and duration: Some plants thrive in full sun, and others are better suited for shaded environments. If the area is close to buildings and trees, survey the space throughout the day to determine light conditions.

- Site topography: This influences the drainage and water saturation of the area. Typically, if the site is located on a slope, the area is subject to drying. If the area is located at the bottom of a slope, it is likely to be wet or saturated after rainfall events for a longer period as the surface water will flow down the slope and settle at the bottom.

- Soil type and texture: Soil texture influences the drainage and saturation of an area and affects the nutrient holding capacity.20 Soil texture refers to the percent of sand, silt, and clay that make up a soil type. Soils with more sand content are good for air movement and water drainage. Soils with higher clay content hold more water, and water moves more slowly through the profile. Depending on the clay, clayey soils can hold onto more nutrients.20

Note that the soil type and texture may not be as expected as the soil is moved during the contouring and construction of the golf course. Soil texture can also change with depth. For example, in the Midlands, sands become finer with depth; in the Upstate, surface soils are sandier than the clayey subsoil. To determine the soil type and texture, refer to the Web Soil Survey website. Soil texture should also be verified in the field. If the area under consideration is for larger plants that will have large root systems or for retaining water, then use an auger (drill) to collect samples deeper in the soil profile.

Once the planting region has been identified and the area has been surveyed, utilize the Clemson University Extension Service Carolina Yards Plant Database to find native plants that match the area’s characteristics. Some plants are native to more than one planting region, and many plants are native to all three South Carolina planting regions. For example, tables 1 and 2 below have examples of common native herbaceous plants that are specific only to one planting region. Tables 3 and 4 below have examples of common native plants that are specific to multiple planting regions as researched from the database. Choose the plants that have the growth requirements that best match those of the site. Doing so will increase the potential for a successful establishment.

A more detailed list of plants per locale can be found in The Natural Communities of South Carolina: Initial Classification and Description.21 As discussed in the next section, The South Carolina Native Plant Society website also gives plant lists for select native plant communities.

Table 1. Native South Carolina plants: Coastal region only.22

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Growth Requirements | Growth Patterns | Type of Plant |

| Sand Cordgrass | Spartina bakeri | Full sun

Grows in sand, clay, and loam High drought tolerance High salt tolerance |

Medium growth rate

Grows 3 to 4 feet high Spreads 3 to 5 feet |

Grass

Evergreen Perennial |

| Coontie Palm | Zamia pumila | Full sun to part sun

Grows in sand, clay, and loam Well-drained soils High drought tolerance High salt tolerance |

Slow growth rate

Grows 2 to 4 feet high Spreads 3 to 5 feet |

Shrub

Evergreen Ground Cover Perennial |

Table 2. Native South Carolina plants: Upstate region only.22

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Growth Requirements | Growth Patterns | Type of Plant |

| Purple coneflower | Echinacea purpurea | Part sun to full shade

Grows in loam Well-drained soils Medium drought tolerance |

Medium growth rate

Grows up to 4 feet high Spreads up to 2 ft |

Herbaceous

Perennial Flowering |

| Woodland phlox | Phlox divaricata | Part sun to full shade

Grows in loam Well-drained soil Low drought tolerance Medium salt tolerance |

Medium growth rate

Grows 10 to 20 inches Spreads up to 12 inches |

Perennial

Ground cover |

| Turtlehead | Chelone lyonii

Chelone glabra Chelone obliqua |

Full sun to part sun

Grows in sand, clay, and loam Soils with acidic to slightly acidic pH Poorly drained soils Medium drought tolerance |

Fast growth rate

Grows 2 to 4 feet high Variable spread |

Perennial

Ground cover Flowering |

Table 3. Native South Carolina plants: Midlands and upstate regions.22

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Growth Requirements | Growth Patterns | Type of Plant |

| Appalachian Sedge | Carex appalachica | Full sun, part sun, full shade

Grows in sand, clay, and loam High drought tolerance |

Medium growth rate,

Grows 0.75 to 3 feet high Spread is variable |

Perennial

Grass Ground cover |

| Serviceberry | Amelanchier canadensis | Full sun

Grows in sand, clay, and loam Medium drought tolerance Grows in well-drained soils |

Slow growth rate

Grows 30 to 40 feet high Spreads 15 to 20 feet |

Deciduous

Tree, Shrub |

| Silky Dogwood | Cornus amomum Mill. | Full sun to part sun

Grows in sand and loam Grows in well, medium, and poorly drained soils |

Slow growth rate

Grows 6 to 10 feet high Spreads 6 to 10 feet |

Perennial

Shrub |

Table 4. Native South Carolina Plants: Coastal, Midlands, and Upstate.22

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Growth Requirements | Growth Patterns | Type of Plant | |

| Blue-eyed Grass | Sisyrinchium angustifolium | Full sun

Grows in clay and loam Acidic to slightly acidic soils Medium drained Low drought tolerance |

Medium growth rate

Grows 1.5 to 2 feet high Spreads 0.5 to 1 foot |

Evergreen

Perennial Grass |

|

| Indian Grass | Sorghastrum nutans | Full sun

Grows in sand, clay, and loam Well-drained soils Medium drought tolerance Medium salt tolerance |

Medium growth rate

Grows 3 to 7 feet high Spreads 1 to 2 feet |

Evergreen

Grass Perennial |

|

| Upland River Oats | Chasmanthium latifolium | Full sun to part sun

Grows in sand, clay, and loam Medium drought tolerance High salt tolerance |

Fast growth rate

Grows 3 to 4 feet in height Spread is variable Consider removing inflorescence before maturing as it can become an invasive plant |

Grass

Perennial |

|

| Big Bluestem | Andropogon gerardii | Full sun

Grows in sand, clay, and loam Well-drained soils High drought tolerance Medium Salt tolerance |

Fast growth rate

Grows 4 to 8 feet in height Spreads 4 to 5 feet |

Grass

Ground cover Perennial |

|

| Bushy Bluestem | Andropogon glomeratus | Full sun

Grows in sand, clay, and loam Well-drained soils Medium drought tolerance Medium to high salt tolerance |

Medium growth rate

2 to 5 feet in height Spreads 1 to 2 feet |

Grass

Ground cover Perennial |

|

| Blue Flag Iris | Iris virginica | Part sun

Grows in sand, clay, and loam Medium to poorly drained soils Medium drought tolerance Low salt tolerance |

Medium growth rate

Grows 4 to 7 feet high Spreads 1 to 3 feet |

Perennial

Ground cover |

|

| Panic Grass | Panicum virgatum | Full sun

Grows in sand and loam soils Acidic to slightly acidic pH Medium drought tolerance Medium salt tolerance |

Fast growth rate

Grows 3 to 6 feet in height Variable spread |

Grass

Ground cover Perennial |

|

| Sweetgrass | Muhlenbergia capillaris | Full sun

Grows in sand, clay, and loam Well-drained High drought tolerance Medium salt tolerance |

Medium growth rate

Grows 3 to 5 feet Spreads 2 to 3 feet |

Grass

Ground cover Perennial |

|

| Little Bluestem | Schizachyrium scoparium | Full sun

Grows in sand, clay, and loam Alkaline pH Well-drained soils Medium drought tolerance High salt tolerance |

Fast growth rate

Grows 2 to 4 feet in height Spreads 1.5 to 2 feet |

Perennial

Grass Ground cover |

|

| Sweet Goldenrod | Solidago odora | Full sun to part sun

Grows in sand, clay, and loam Acidic pH Medium drought tolerance Medium salt tolerance |

Medium to fast growth rate

Grows 2 to 4 feet in height Spreads 1 to 2 feet |

Shrub

Evergreen Perennial Grass |

|

Native Planting in Out-of-Play Areas as Models

Golf courses that incorporate native plants into out-of-play areas can be used as models to help educate both the public, golf course managers, and other land managers. Education can include posting informative signage such as:

- To feature specific native plants. The plant community, climate, landscape, soil features, and growth habits that the plants naturally are related to. Other information on the current natural extent, cultural and medicinal uses, as well as where plants can be purchased.

- To convey general information. Consider including signage that defines what are native plants, common plant communities found in the area, the natural history of the golf course (aerial photography before development may be included to document previous plant communities), different growth habits of plants, plant tolerance to light and shade, soil moisture terminology and explain the Endangered Species Act and related terminology (i.e., rare, endangered, threatened).23

To minimize costs associated with signage, golf courses can utilize QR codes on signs to connect readers to a website that provides the previously mentioned information and link to this article and other resources. With easy access to information, it could encourage others to install native plants in other landscapes. In addition, a website is easier and less costly to update compared to informational signs. Without education on the plant species, an average person might think he/she can grow it with ease. However, some native plants can be notoriously challenging for an individual to grow. Sweet Goldenrod (Solidago odora) has a showy flower and is known to attract many pollinators but may not compete well with aggressive species such as Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis). Elderberry is also native to South Carolina but has a rapid growth rate making it hard to control in some scenarios. The bottom line is education is key.

Obtaining Native Plants

Consider hiring a landscape contractor specializing in designing native plantings for larger areas that are to be planted as a native plant community. For smaller areas, always try to purchase plants from a grower specializing in growing native plants. The South Carolina Native Plant Society website (scnps.org/about-the-plants) offers information on native plant sales and a list of retail nurseries that sell native plants. The Lowcountry Native Plant Society chapter provides grants to help install, maintain, and educate about native plantings.

Digging up native plants from public land such as the forest and collecting seeds from the forest is against the law. The four significant reasons defined by the US Forest Service include:

- Doing so reduces the plant’s ability to reproduce and adversely affects the long-term survival of the plant in that location.

- Doing so can adversely affect pollinators and other animals that depend on that species for food and cover.

- Removing plants from our national forests and grasslands prevents other visitors from enjoying our natural heritage.

- Most wildflowers do not survive being transplanted when removed from their natural habitat.20

Contact your local independent garden center and ask them to obtain harder-to-find natives. If designing a larger planting area, your landscape consultant, contractor, or architect, should consult in advance with growers to find out if plants are available or to enable growers to increase production stocks so the desired species will be available for the project. Clemson University Extension Service also offers a South Carolina Native Plant Certificate, and information is provided on the Home & Garden Information Center website. Audubon International provides information on their website, auduboninternational.org, (and in some instances, technical services and seeds) for shoreline planting, benefits of tall grasses, and creating gardens for specific purposes on golf courses. Golf courses can obtain certification for their sustainable approaches to course management through the Audubon Cooperative Sanctuary Program, and information is available on the website.

References Cited

- Uttara S, Bhuvandas N, Aggarwal V. Impacts of urbanization on environment. International Journal of Research in Engineering and Applied Sciences. 2012 Feb [accessed 2022 Mar 5];2(2):1637–1645. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nishi-Bhuvandas/publication/265216682_Impacts_of_urbanisation_on_environment/links/5405ba200cf23d9765a729ef/Impacts-of-urbanisation-on-environment.pdf.

- Kiss D. An environmental frame of reference: Golf course design in out-of-play areas [master’s thesis]. Blacksburg (Va).1998 May. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.411.1632&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- Mullerscharer H, Schaffner U, Steinger T. Evolution in invasive plants: implications for biological control. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2008 Jun [accessed 2022 Mar 5];19(8):417–422. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcs142p2_053261.pdf.

- Merola-Zwartjes M. Assessment of grassland ecosystem conditions in the southwestern United States. U.S Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 2005 Sep [accessed 2022 Mar 5];2:71–73. https://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs/rmrs_gtr135_2/rmrs_gtr135_2_071_140.pdf.

- Owen W. TERR-2: The history of native plant communities in the South. USDA Forest Service. [accessed 2022 Mar 5]; 1-24. https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/sustain/draft/terra2/terra2.pdf.

- Daane KM, Hogg BN, Wilson H, Yokota GY. Native grass ground covers provide multiple ecosystem services in Californian vineyards. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2018 Mar [accessed 2022 Mar 5];55(5):2473–2483. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.13145 https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1365-2664.13145.

- Helfand G, Park J, Nassauer J, Kosek S. The economics of native plants in residential landscape designs. 2006 Nov [accessed 2022 Mar 5];78(3):229–240. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016920460500112X?casa_token=2-aPU1kEWp8AAAAA:p9NyRY3xoYwkEtyeEiDxg9ZRTdifGwVfQOPKohhgp1bbiTfaOqv7QNV__WaXo3UhWtOp8XDgQ.

- Nelson M. Natural Areas: establishing natural areas on the golf course. USGA Green Section Record. 1997 Nov/Dec [accessed 2022 Mar 5];1–11. https://www.usga.org/content/dam/usga/pdf/imported/course-care/971107.pdf.

- Dale A. Wildflowers Bring in Beneficial Insects. Golf Course Superintendents Association of America. 2020 Feb [accessed 2022 Mar 5]; https://www.gcmonline.com/course/environment/news/wildflowers-golf-course-beneficial-insects.

- Norton B, Evans K, Warren P. Urban Biodiversity and Landscape Ecology: Patterns, Processes, and Planning. Current Landscape Ecology Reports. 2016 Nov [accessed 2022 Mar 5];1(4):178–192. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40823-016-0018-5.

- Russo A, Escobedo FJ, Cirella GT, Zerbe S. Edible green infrastructure: An approach and review of provisioning ecosystem services and disservices in Urban Environments. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 2017 May [accessed 2022 Mar 5];242:53–66. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2017.03.026 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167880917301457?casa_token=agMfButalmkAAAAA:HGJX9pJrJfX7FFjVtRaz0MnKC0FVOq1LrO9dEu5gLtSYUIWld-yShftJqrnHTMCbI6Hyn1MukA.

- O’Malley C, Piroozfar P, Farr E, Pomponi F. Urban heat island (uhi) mitigating strategies: a case-based comparative analysis. 2015 Dec [accessed 2022 Mar 5];19:222–235 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2210670715000657?casa_token=GH_-2NHtuhMAAAAA:QGKE5sdux_YJeXImm16fAIeXbqcxEWYFd1gYR_1abD9YpUuMISZTxtX9zt32ojhO9TkDQ8dUqA.

- McPherson E. Functions of buffer plantings in urban environments. Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Environment.1988 Aug [accessed 2022 Mar 5];281–298. https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/0167880988900266?token=5AC58F09300430CEC3212DA565F41A7AC8938A36C6FA44E4CC1F835DCE69A14747A5691B8677FC1ADC07D7462B54A1FA&originRegion=us-east-1&originCreation=20210818132211.

- Rule 2 – The Course. Liberty Corner (NJ): United States Golf Association; 2022 [accessed 2022 Mar 5]. https://www.usga.org/content/usga/home-page/rules/rules-2019/rules-of-golf/rule-2.html.

- Hodgkison S, Hero J, Warnken J. The efficacy of small-scale conservation efforts, as assessed on Australian golf courses. Biological Conservation. 2007 Apr [accessed 2022 Mar 5];135(4):576–586. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006320706004873.

- Reed M, Deason J, White D, Park D. The nitty gritty of South Carolina soil orders. Focus on Creative Inquiry. Paper 41. 2014 [accessed 2022 Mar 5]; http://tigerprints.clemson.edu/foci/41.

- Bond W, Keane R. Ecological effects of fires. In: Roitberg BD, editor. Reference module in life sciences. Amsterdam (NL): Science Direct, Elsevier: 2017 [accessed 2022 Mar 5]. https://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs_journals/2017/rmrs_2017_bond_w001.pdf. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-809633-8.02098-7.

- Dibull N. Mowing as an alternative to spring burning for control of cool season exotic grasses in prairie grass plantings. In: Clambey GK, Pemble RH, editors. The Prairie: Past, Present, and Future. Proceedings of the Ninth North American Prairie Conference; 1984 Jul 29-Aug 1; Moorehead, MN. Fargo (ND): Tri-College University Center for Environmental Studies; 1986 [accessed 2022 Mar 5]. https://www.prairienursery.com/media/pdf/mowing-vs-burning-for-prairie-management.pdf.

- USDA Plant Database. Greensboro (NC): United States Department of Agriculture; [accessed 2022 Mar 5]. https://plants.usda.gov/home.

- Wildflower Ethics and Native Plants. Washington (DC): U.S. Forest Service. Forest Service Shield; [accessed 2022 Mar 5].https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/ethics/index.shtml.

- Nelson J. The natural plant communities of South Carolina: initial classification and description. South Carolina Marine and Resource Department. 1986 Feb [accessed 2022 Mar 5];1–64. http://herbarium.biol.sc.edu/publications/JBNDoc.pdf.

- Carolina Yards Plant Database. Clemson (SC): College of Agriculture, Forestry and Life Sciences Clemson University; 2022 [accessed 2022 Mar 5]. https://www.clemson.edu/extension/carolinayards/plant-database/index.html.

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Washington (DC): U.S. Department of the Interior; [accessed 2022 May 23]. https://www.fws.gov/law/endangered-species-act.

Additional Resources

Barnette E, Sawyer CB, Park D. Water Withdrawal Regulations Every Agricultural User in South Carolina Should Know. Clemson (SC): Clemson Cooperative Extension, Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension; 2020 Oct. LGP 1094. https://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/water-withdrawal-regulations-every-agricultural-user-in-south-carolina-should-know/.

Nelson JB. The natural communities of South Carolina: initial classification and description. Columbia (SC): SC Wildlife and Marine Resources Department, Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries; 1986 Feb. A Check for Wildlife. http://herbarium.biol.sc.edu/publications/JBNDoc.pdf.

Ecoregional Planting Guides. San Francisco (CA): Pollinator Partnership; c2022. https://www.pollinator.org/guides.