Gummy stem blight is one of the most common foliar diseases on watermelon, muskmelon, honeydew, and other specialty melons in the southeastern United States. How severe the disease becomes depends on rainfall and dew periods. Growers and Extension agents should focus management and education efforts on crop rotation and careful fungicide selection to effectively manage this disease.

Disease Symptoms and Pathogen Signs

Gummy stem blight appears in three distinct phases: leaf spots, crown cankers, and fruit rots. The fruit rot phase is called black rot. The common name “blight” indicates the disease often affects the entire plant. However, gummy stem blight starts as distinct dark spots.

Symptoms

Gummy stem blight affects all above-ground parts of diseased cucurbit plants, including leaves, petioles (leaf stems), vines, crowns, tendrils, pedicels (flower stalks), and peduncles (fruit stems).1 Leaf lesions are round or triangular, particularly those at leaf edges, brown on melons and dark brown on watermelon. The centers of spots often are lighter brown than the surrounding portions. Leaf spots may have dark and light brown rings. More than half the leaf spots start at the margins or touch the margins of leaves (figure 1). Leaf spots sometimes are found along the midvein. As leaf spots expand, they merge, which leads to leaf blighting (figure 2). Lesions on petioles may cause the entire leaf to collapse.

Cankers on crowns, main stems, or vines are more common on melons (Cucumis melo varieties) than on watermelon (Citrullus lanatus). Cankers are light brown, beige, or off-white. On melons, young cankers start as water-soaked, green lesions, then become dry, rough, and cracked. Drops of gummy, amber plant sap may appear on cankers (figure 3). Although this symptom gives gummy stem blight its common name, this symptom is not diagnostic; stem injuries and Fusarium wilt also cause gumming.

On watermelon, gummy stem blight can be distinguished from anthracnose by the larger leaf spots, larger lesions that completely encircle petioles, and the presence of crown cankers, which do not form with anthracnose. Anthracnose leaf spots are angular, irregular, or star-shaped, while leaf spots of gummy stem blight generally are round.2 The centers are more likely to drop out of leaf lesions due to anthracnose than gummy stem blight (figure 4).

Figure 4. Left photo shows diseased watermelon petiole with symptoms of gummy stem blight that completely encircle the petiole. Right photo shows watermelon petiole with discrete spindle-shaped lesions of anthracnose and leaf spots with “shot-hole” centers. Image credit: Anthony Keinath, Clemson University.

Black Rot on Fruit

Melon fruit are more likely to have black rot than watermelon fruit. Black rot also is more common on western-type cantaloupes, cultivars that produce lightly sutured, heavily netted fruit with firm ripe flesh, than on eastern-type muskmelons, cultivars that produce deeply sutured, lightly netted fruit with soft ripe flesh. The rot normally starts at the stem end or in cracks in the fruit. External symptoms on melon are not diagnostic. The flesh becomes watery and discolored (figure 5). Black mold grows in the seed cavity.

On watermelon, black rot is rare. It commonly starts at the blossom end of the fruit, so it may be mistaken for blossom end rot since both rots are dark, leathery, and slightly sunken. Black rot lesions tend to be larger and moister than blossom end rot lesions. Signs of the pathogen described below can be used to distinguish black rot from blossom end rot.

Signs

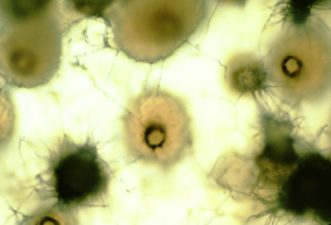

Fruiting bodies form on all parts of diseased cucurbit plants, although fruiting bodies are more common on leaves and crowns than on fruits.3 On leaves, fruiting bodies form first in the center of spots (figure 6). Gummy stem blight can be confirmed if dark brown to black sexual fruiting bodies (called pseudothecia) are present with asci or ascospores inside them. At 50 to 80 × magnification under a dissecting microscope, hyaline (clear) sterile hairs may be seen protruding from the fruiting bodies under high relative humidity. More commonly, tan to brown asexual fruiting bodies (called pycnidia) with conidia are present when gummy stem blight is observed during the growing season. Under high relative humidity, a mass of conidia may ooze out the opening in the center of the pycnidium (figure 7). Dead leaf hairs in lesions may be mistaken for fruiting bodies. Leaf hairs, however, are two to three times as wide as fruiting bodies. Fruiting bodies are rare on muskmelon fruit but may be present in large lesions on watermelon fruit.

Pathogen Basics

Gummy stem blight is caused by three species of the fungus Stagonosporopsis.4 Stagonosporopsis citrulli is, by far, the most common species on watermelon and melons in the southeastern United States. Most of the information in this publication is based on research with this species. The second, less common species (less than 5% of collections) is Stagonosporopsis caricae. The third species, Stagonosporopsis cucurbitacearum, is more common in the northeastern and mid-Western United States than in the Southeast. Previously, all three species were named Didymella bryoniae or Phoma cucurbitacearum.

Pathogen Spread

Fungal pathogens produce spores to allow them to spread to new plant hosts, leading to more diseased plants in the field. Stagonosporopsis produces two types of spores, conidia and ascospores, so it has more options to spread. Conidia are spread short distances by rain, while ascospores are spread long distances by air. Thousands of conidia are produced on diseased leaves and other plant parts. They are spread by rain splash or overhead irrigation when raindrops fall on a leaf and spores are splashed to other leaves. Hundreds of ascospores are produced on diseased vines and other plant parts. They can be spread at least 1,200 ft by wind.5 Both ascospores and conidia infect leaves and other plant parts to initiate gummy stem blight.

Pathogen Survival

At the end of the growing season, especially in the fall, Stagonosporopsis citrulli grows throughout vines and crowns, turning them black with thousands of pseudothecia as the fungus prepares for survival and spread by air.5 In South Carolina, Stagonosporopsis citrulli survives seven months in diseased vines and more than two years in diseased crowns.6,7 Survival in crowns is 3.5 months shorter when infested debris is buried in soil instead of left on the soil surface or on raised beds mulched with plastic. Twice as many crowns left on plastic had the pathogen as crowns on the soil surface. The fungus can survive in crop debris pieces as small as ½ inches long. It is impossible to physically remove all the debris to clean up a field.

Stagonosporopsis species also survive in seed. It is likely that seed are infected when the fungus invades flowers and grows into the developing seed. Growing melon transplants in a greenhouse increases the chances that the pathogen in a few infected seed, like 4 per 1,000, will spread to many more transplants, 5 per 100 or more.8

Moisture and Gummy Stem Blight

A film of moisture on leaves is necessary for gummy stem blight to grow and spread. The gummy stem blight fungi are completely dependent on moisture for growth. While leaf spots of the cucurbit diseases anthracnose and downy mildew will enlarge without moisture, leaf spots of gummy stem blight will not. It takes 24 to 48 hours of wet weather for a serious epidemic of gummy stem blight to start in a field.

Gummy stem blight is a main reason for failures of fall watermelon crops in South Carolina because long dew periods, frequent rainfall, and tropical storms cause leaves to remain wet for extended periods, which creates optimum environmental conditions for severe gummy stem blight.

Management of Gummy Stem Blight

Crop Rotation

Based on what we know about the survival of S. citrulli, the main source of the pathogen is infested crop debris. Cropping fall watermelon in the same field after spring watermelon leads to very severe outbreaks of gummy stem blight that is difficult to manage with fungicides.

To manage gummy stem blight, two years is the minimum rotation interval between watermelon and muskmelon crops in the same field. Put another way, there should be a 2-year period without melons to allow enough time for the infested debris to decay. The rotation interval starts when the first crop is disked and ends when the second crop is transplanted. For example, if a field was planted to watermelon in 2021, then it should not be cropped to watermelon or muskmelon until spring 2024 so debris can decay completely during 2022 and 2023. Because gummy stem blight infects only crops in the squash plant family, any agronomic or vegetable crops in other families can be planted during the cucurbit-free period. Summer squash and zucchini (Cucurbita pepo varieties) may be planted in the second year (2023) of the rotation period since these cucurbits are less susceptible to foliar blight and black rot.1

Fungicides

Fungicide applications to manage gummy stem blight are necessary to produce watermelon and muskmelon in the southeastern United States to prevent losses of yield and profits.9 Current fungicide recommendations are given in the Southeastern U.S. Vegetable Crop Handbook10 and 2022 Watermelon Fungicide Guide.11

Fungicide Resistance

The gummy stem blight fungi can become resistant to fungicides applied frequently. Fungicide resistance is measured based on how common resistant isolates occur (also called the frequency) and the level of resistance to a particular fungicide. Resistance is normally expressed as moderately or highly resistant; highly resistant isolates result in fungicide failure at field rates. Stagonosporopsis citrulli is highly resistant to thiophanate-methyl (FRAC Code 1), QoI fungicides (FRAC Code 11), and some SDHI fungicides, like Endura and Fontelis (FRAC Code 7).11,12 Highly resistant isolates are found throughout the United States. Although Luna fungicides also are FRAC Code 7, there is no cross resistance between Luna and other FRAC Code 7 fungicides. Stagonosporopsis citrulli and Stagonosporopsis caricae are moderately resistant to tebuconazole (FRAC Code 3) in some areas of Georgia and South Carolina.13

Disease-Free Transplants

Gummy stem blight can be present on watermelon and muskmelon transplants. Growers should carefully inspect transplants for brown spots on cotyledons or true leaves and for water-soaked areas on the seedling stems. If any diseased seedlings are found, it is likely some of the surrounding seedlings also will become diseased, even if they appear healthy when the shipment is received. Growers should discard as many seedlings in a flat with diseased seedlings as is practical, based on the number of seedlings available and the number needed in the field. If seedlings that appear healthy but come from a tray with diseased seedlings are needed to make the recommended number of plants per acre, a successful crop can still be grown in the spring with regular and timely fungicide applications.8

References Cited

- Keinath A. Differential susceptibility of nine cucurbit species to the foliar blight and crown canker phases of gummy stem blight. Plant Disease 2014 Feb;98(2):247–254.

- Keinath, A. P. 2013. Diagnostic guide for gummy stem blight and black rot on cucurbits. Plant Health Progress. doi:10.1094/PHP-2013-1024-01-DG

- Keinath A. Reproduction of Didymella bryoniae on nine species of cucurbits under field conditions. Plant Disease 2014 Oct;98(10):1379–1386.

- Stewart J, Turner A, Brewer M. Evolutionary history and variation in host range of three Stagonosporopsis species causing gummy stem blight of cucurbits. Fungal Biology 2015 May;119(5):370–382.

- Rennberger G, Turechek W, Keinath, A. Dynamics of the ascospore dispersal of Stagonosporopsis citrulli, a causal agent of gummy stem blight of cucurbits. Plant Pathology 2021 Oct;70(8):1908–1919.

- Keinath A. Survival of Didymella bryoniae in buried watermelon vines in South Carolina. Plant Disease 2002 Jan;86:(1)32–38.

- Keinath A. Survival of Didymella bryoniae in infested muskmelon crowns in South Carolina. Plant Disease 2008 Aug;92(8):1223–1228.

- Keinath A. 1996. Spread of Didymella bryoniae from contaminated watermelon seed and transplants in greenhouse and field environments. Pages 65-72 in: Recent Research Developments in Plant Pathology, Vol. 1. Research Signpost, Trivandrum, India.

- Keinath A. Effect of protectant fungicide application schedules on gummy stem blight epidemics and marketable yield of watermelon. Plant Disease 2000 Mar;84(3):254–260.

- Kemble JM, senior editor. Bertucci MB, Jennings KM, Meadows IM, Rodrigues C, Walgenbach JF, Wszelaki AL, editors. Vegetable crop handbook for the southeastern US. Sparta (MI): Great American Media Services. 2022. www.vegcrophandbook.com.

- Keinath AP, Miller GA. Watermelon Fungicide Guide for 2022. Clemson (SC): Clemson Cooperative Extension, Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension; 2022 Mar. LGP 1001. https://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/watermelon-fungicide-guide.

- Thomas A, Langston, Jr. D, Sanders H, Stevenson K. Relationship between fungicide sensitivity and control of gummy stem blight of watermelon under field conditions. Plant Disease 2012 Dec;96(12):1780–1784.

- Li H-X, Stevenson K, Brewer, M. Differences in sensitivity to a triazole fungicide among Stagonosporopsis species causing gummy stem blight of cucurbits. Plant Disease 2016 Oct;100(10):2106-2112.

Additional Resources

Keinath AP, Miller GA. Watermelon fungicide guide for 2022. Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension. 2022; LGP 1001: https://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/watermelon-fungicide-guide/.