Feeding programs may vary considerably among South Carolina horse owners, but nutrition fundamentals should remain the same. The base for all horse diets should be quality forage with more energy-dense concentrates or grains as needed. Balanced nutrients should be fed according to the stage of production, growth, and activity level. Unlike other livestock species, which are often fed for weight gain and meat quality for relatively short periods, horses are fed to maintain a degree of serviceability for a much longer timespan. Improper feeding management can lead to digestive disturbances, substandard athletic performance, and poor health in general.

Digestion

Horses are classified as non-ruminant herbivores; however, adaptations to the hindgut allow the horse to be much more suited for digesting roughages than other non-ruminants. They are continuous grazers, and because the stomach is made up of glandular and non-glandular portions, they require a somewhat constant supply of forage to maintain good digestive health. The glandular portion secretes digestive enzymes, acids, and its own protective mucous almost constantly; the non-glandular portion is protected only by the natural buffering ability of the saliva produced while eating.

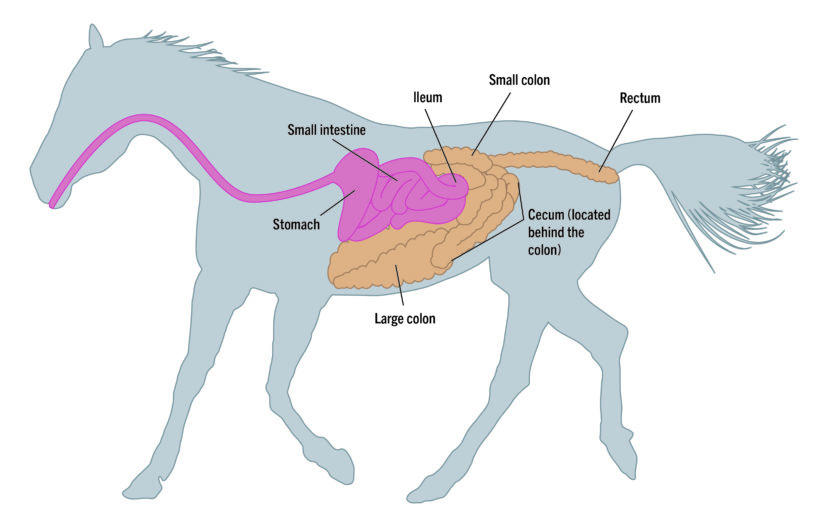

The foregut includes the mouth, esophagus, stomach, and small colon. The stomach is relatively small compared to the rest of the digestive tract (figure 1) and, therefore, can only contain small amounts of any feedstuff at one time. Only some enzymatic digestion occurs in the stomach. Digestion of most soluble carbohydrates, fat, and protein occurs in the small intestine, where a large portion of nutrient absorption also occurs. The hindgut (cecum, large colon, and small colon) contains an active population of microbes that break down fibrous (structural) carbohydrates into volatile fatty acids (VFAs), which can then be absorbed and used as an energy source by the horse. Large meals of highly soluble carbohydrates, such as the starch and simple sugars present in various cereal grains, can spill over into the hindgut, where microbial fermentation produces lactic acid. Lactic acid and gas accumulation in the hindgut can cause digestive disorders such as colic or even founder (laminitis).

Nutrients

There are five essential nutrients that the equine diet should supply, including water, fats and carbohydrates, protein, vitamins, and minerals.

Water

Water is the most critical nutrient.

- Horses drink eight to twelve gallons of water per day (about one gallon per one-hundred pounds of body weight). Intake increases by as much as four times during hot temperatures, humidity, hard work, lactation, or extra dry matter consumption (hay in the winter versus lush spring pasture).

- Although water demands are higher in the hot, humid summer months, consumption should also be monitored during cooler months. Cold water can decrease consumption, coupled with the increased dry hay consumption of winter could lead to gut motility issues.

- An adequate, clean supply of water should be available at all times. Signs of dehydration include decreased feed intake or physical activity, dry mucous membranes, dry feces, or reduced capillary refill time.

Fats and Carbohydrates

Energy is mainly supplied by the fats and carbohydrates and fats in a horse’s diet and is highly affected by the digestibility of these two components.

- Fat is over two times more energy-dense than carbohydrates and is usually supplied in minimal quantities in the equine diet.

- Carbohydrates are the primary energy source in most feed and forage sources.

- Soluble carbohydrates (simple sugars and starch) are readily broken down into glucose in the small intestine and absorbed.

- Fibrous carbohydrates that make up the plant cell wall (cellulose, hemicellulose) and, to a degree, lignin must be digested by bacterial fermentation in the cecum. The volatile fatty acids produced by fermentation can then be absorbed in the hindgut for energy. It is estimated that a horse consuming a mostly forage diet will meet more than 80% of its energy needs with these volatile fatty acids.1

Protein

Protein is broken down into amino acids for muscle growth and repair during growth or exercise.

- Most adult horses only require between 8% to 10% crude protein in their diet; however, higher protein content and quality is important for lactating mares, young growing foals, and high-level athletes. For the growing and performing horses, consider the quality of the protein. Higher quality protein sources include more of the essential amino acid lysine. Monitoring protein quality and content can help prevent overfeeding protein

- Excess protein results in increased water intake, urination, and increased sweat losses during exercise.

- Signs of protein deficiency include rough hair coat, weight loss, reduced growth, milk production, and performance.

Vitamins

Adult non-working horses or those in light work usually do not need a vitamin supplement if they consume fresh forage and/or a premixed ration.

- Vitamin D is found in sun-cured hay sources, and horses on pasture obtain Vitamin D from sunlight. Fresh green forages provide Vitamins A and E. Horses with limited turn-out or those eating either weathered forage or forage from long-term storage may need supplementation of these vitamins.

- Microbes produce vitamin K and B-complex in the hindgut, and the liver produces vitamin C; therefore, supplementation of these vitamins is not needed.

Minerals

Minerals are needed in small quantities in the diet to maintain body structure, fluid balance in cells, nerve conduction, and muscle contraction. As with other nutrients, the National Research Council’s Nutrient Requirement of Horses lists recommended daily amounts of macro-minerals (calcium, phosphorous, sodium, potassium, chloride, magnesium, and sulfur) and micro-minerals (Iron, Zinc, Copper, Selenium, Manganese, Iodine, Cobalt).1 Minerals can be balanced if the mineral content of the feed and forage is known. It is common practice to provide a free-choice mineral supplement.

- Pay attention to the calcium: phosphorus ratio. Calcium is high in most forages, and higher phosphorus levels are characteristic of grain diets. The ratio of these two minerals should be as close to 2:1 as possible in young, growing horses. The ratio becomes more flexible for mature horses but should never be inverted.

- Young, growing horses may need additional calcium, phosphorous, copper, and zinc during their first two years.

- Aside from disorders caused by deficiencies or over-abundance (toxicities), some mineral interactions can reduce the absorption of available minerals.

- It is crucial to select a mineral balanced for the horse and its diet and environment. A ration balancer is a good way to ensure a horse on forage consumes the necessary amount of minerals.

- Always provide free-choice salt (sodium chloride); if possible, use a loose form to increase consumption. Horses in hot environments such as South Carolina or those with high exercise regimens will deplete sodium, chloride, and potassium in the sweat; therefore, these horses may need an electrolyte supplement.

- Each component plays a critical role in the health of the horse. The equine nutrition market is full of supplements and different forms of these essential nutrients.

Forage

Quality forage from pasture or hay should be the base of every equine diet, no matter their relative activity level. Horses need forage in their diet to maintain normal digestive function, and forage-based diets can be much more economical than feeding large quantities of grain concentrates.2 At least 1% of a horse’s body weight should be provided in forage dry matter (DM) per day.2 Dry matter is the portion of feed or forage left after water has been removed. Dry matter must be considered when comparing fresh pasture to hay because fresh grasses can contain up to 90% water (10% DM), whereas hay contains between 10% to 15% water (between 85% to 90% DM). By the above recommendation, a 1,000-pound horse should have a minimum of 10 lb of forage DM. The as-fed amount in table 1 is what the horse must consume to achieve 10 lb of forage DM. Water is bulky, and a horse on pasture must consume more fresh grass than a hay-fed horse to reach the minimum 10 lb of forage DM.

Table 1. Minimum forage consumption of 1,000-pound horse.

| Diet | Water (%) | DM (%) | Target (lb)/ DM (%) | As-fed Amount (lb) |

| Pasture | 70 | 30 | 10/ 0.3 = | 33.3 |

| Hay | 10 | 90 | 10/ 0.90 = | 11.1 |

Pasture

Properly managed grass or mixed grass-legume pastures provide protein, vitamins, and an excellent energy source and meet the nutritional needs of most adult horses. During the growing season, hay and concentrate feeding can be drastically reduced and even eliminated in mature, idle, and early-pregnancy horses with access to productive pastures.1,3,4 South Carolina has an excellent climate for growing high-quality forages, but pasture management is key.

Horses may consume an average of 2% of their body weight per day in forage dry matter. If the major nutrient source is pasture, a 1,000-pound horse will collectively consume and waste approximately three tons of forage dry matter on average during a typical 6-month grazing season. Thus, with average management, it would take about two acres of pasture to meet the nutrient needs of a mature horse.5 Of course, pasture carrying capacity will depend on such variables as soil type, soil fertility, drainage conditions, amount of rainfall, time of year, and type of forage species present.

Hay

Figure 2. Coastal bermudagrass hay on the left and fescue hay on the right. Image credit: Cassie W. LeMaster, Clemson University.

Hay quality can be determined by confirming it is free from dust, mold, and weeds. Hay quality is also heavily affected by its maturity at the time of cutting and the storage method. The nutritional value of hay is highest when it is cut at an early leafy stage of growth compared to mature stemmy hay, which is much higher in indigestible fiber. Hay can be grass or legume. Common grass hays fed to horses in South Carolina are coastal bermudagrass, fescue, and timothy (primarily shipped in from other states) (figure 2). Cool-season grasses (Tall-Fescue) are usually higher in quality than warm-season varieties (bermudagrass), depending on specific cultivars. For more information on forage species appropriate for South Carolina’s climate, refer to the publication, “Equine Pasture Management.” The most common legume hay fed to horses is alfalfa,6 and some grass hays also contain a clover mixture. Alfalfa is a good option for growing horses or those with greater nutrition requirements because it is higher in digestible energy, calcium, and protein than grass hays.4

Concentrates

Grains

Figure 3. A commercial grain mix containing oats (left) and corn (right). Image credit: Cassie W. LeMaster, Clemson University.

Often, an all-forage diet does not meet a horse’s energy needs in higher production situations, such as those exercising heavily, growing, or lactating. Adding concentrates in the form of cereal grains is an easy way to add extra energy to their diet. Commercial grain mixes are also a good source of protein, phosphorous, and vitamins.

Most commercial grain mixes contain several different grain sources, such as oats, corn, and barley (figure 3). Oats are the most common horse grain as they are higher in fiber content, more palatable, digestible, and considered the safest of the three. Barley is a little higher in digestible energy than oats, and corn is the highest. Corn is low in fiber and very energy-dense, making it easy to overfeed and cause obesity.

All horses do not need grain in their diet, as their digestive system is well-adapted to utilizing forages. Because their relatively small stomach size limits the amount they can eat at one time, a horse’s ration should contain a maximum of 50% grain if it is under a heavy workload. The greater proportion of grain in the diet, the higher the risk of digestive upset, ulcers, laminitis, and obesity. Along with this, grain feeding should be split into two to three meals per day (at as regular and even intervals as possible) to limit the amount consumed at one time. For heavy grain diets, limit the size of each grain meal to 0.5% of the horse’s body weight.2

Fat Supplements

Fat supplements can be used as a top dressing on feed to provide extra calories. Since fats are more energy-dense than the grains listed above, small amounts can be fed as a way to safely add weight to a thin horse without overloading the digestive system. Corn and other vegetable oils, flaxseed oil, and rice bran are common fat supplements for horses. Rice bran is a commercially available by-product that contains about 20% crude fat. If adding an oil supplement as a top dressing (as it is not palatable by itself), start by adding one-fourth cup per feeding and increase to no more than two cups per day over two weeks.

Restricted Calorie Diets

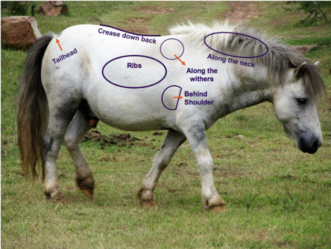

Figure 4. Identified fat-accumulating areas on an overweight pony. Image credit: White and Grey Horse, by Magda Ehlers, provided by Pexels.

Some ponies and certain horse breeds prone to weight gain (commonly known as “easy-keepers”) do not need to consume concentrates, as obesity problems in these equines can occur quickly. There are many health problems associated with obesity in horses, including metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and laminitis7; therefore, an overweight horse’s diet should be carefully controlled. Good management involves evaluating the fat cover and weight of the horse by body condition scoring. This method utilizes visual inspection of common fat-accumulating areas (e.g., neck, ribs, behind shoulders, tail head) (figure 4) as a helpful tool for deciding if your horse is receiving appropriate amounts of feed.8

If your horse is overweight, reducing the calories in the diet and increasing exercise are necessary steps to returning your horse to a healthy state. Always start a restricted-calorie diet by cutting out grain concentrates and feeding an all-forage diet. Pasture turn-out time is beneficial for increasing physical activity, but when pasture grass provides too many calories, horses may need to be restricted to a dry lot.

Dry lots are mainly sand or dirt and contain very little forage for grazing if any at all. Restricting overweight horses to a dry lot allows you to control how much they eat by offering only hay while still allowing them to get needed exercise. If a dry lot is not available, the horse can be fitted with a grazing muzzle to restrict grass intake while in the pasture. Although limiting the number of hours a horse is allowed in the pasture may be a viable option to reduce feed intake, research has shown that most horses just increase their consumption rate to make up the difference.9

Restricting the energy of a diet without sacrificing other essential nutrients is often a difficult task. Remember, horses need at least 1% of their body weight each day in forage at regular intervals to maintain proper digestive health to help reduce the risk of ulcers and stereotypies.2 Good quality hay will likely provide the needed protein and some vitamins, but minerals may be lacking. Supplementing the hay with a vitamin/mineral ration balancer is recommended. As with all changes where diet and nutrition are integral, weight loss in horses should be gradual to avoid unintentional health problems. Consult an equine nutritionist for assistance with developing a feeding regiment that is effective, simple, and affordable.

References Cited

- National Research Council (NRC). Nutrient requirements of horses. 6th ed. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2007. doi:10.17226/11653.

- Burk A, Quinn R. Trimming the fat: weight loss strategies for the overweight horse. In: Horse industry handbook. McDonald (NM): American Youth Horse Council; 2011. HIH 790-1–4.

- Johnson KD, Russell MA. Maximizing the value of pasture for horses. West Lafayette (IN): Purdue University, Animal Sciences Department, Cooperative Extension Service; 1993. ID-167. https://www.extension.purdue.edu/extmedia/ID/ID-167.html.

- National Research Council (NRC). United States-Canadian tables of feed composition: nutritional data for United States and Canadian feeds, third revision. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 1982. doi:10.17226/1713.

- Wallau M, Johnson EL, Vendramini J, Wickens C, Bainum C. Pastures and forage crops for horses. Gainesville (FL): University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Extension. 2019 Feb. Publication #SS-AGR-65. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/aa216.

- Kentucky Equine Research. Hay Selection for horses. Versailles (NY). 2010 Nov [accessed 2020 Mar 30]. https://ker.com/equinews/hay-selection-for-horses/.

- Johnson PJ, Wiedmeyer CE, Messer NT, Ganjam VK. Medical implications of obesity in horses-lessons for human obesity. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. 2009 Jan;3(1):163–164.

- Henneke DR, Potter GD, Kreider JL, Yeates BF. Relationship between condition score, physical measurements and body fat percentage in mares. Equine Veterinary Journal. 1983 Oct;15(4):371–372.

- Glunk EC, Pratt-Phillips SE, Siciliano PD. Effect of restricted pasture access on pasture dry matter intake rate, dietary energy intake, and fecal pH in horses. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science. 2013 Jun 1;33(6):421–426.

Additional Resources

Flowers B, Van Vlake L, Starnes A, LeMaster CW, Burns MB. Equine Pasture Management. Clemson (SC): Clemson Cooperative Extension, Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension; 2020 Aug. LGP 1086. https://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/equine-pasture-management/.