Livestock need access to adequate volumes of clean water every day to grow and thrive. However, unrestricted livestock access to surface waters could impair surface water quality for livestock, aquatic organisms, and downstream users.1 This publication provides helpful information for livestock producers, consultants, and downstream stakeholders related to livestock pond design, water quality issues in livestock ponds, and management of upland drainage areas to protect water quality in livestock ponds.

Construction of farm ponds for watering livestock became more prevalent in the 1930s due to programs created by the Soil Conservation Service (now known as the Natural Resources Conservation Service or NRCS). The move toward pond construction came on the heels of the soil survey results from which Hugh Hammond Bennett declared that soil erosion was a “national menace.”2 Establishing more pastureland in exchange for badly eroded cropland was one solution to reducing the erosion crisis. Increased acreage of pastureland led to a need for accessible water for grazing livestock.3 Today, increased awareness of the importance of water quality protection has led researchers to study how pond design and upland management influence water quality for those who use the pond (e.g., livestock) or are downstream recipients of water from the pond.

Pond Design

The design of a pond for watering livestock depends on the water source.4,5 Embankment ponds are formed by building a dam to collect surface water and stormwater runoff in a watershed. Excavated ponds are dug to capture groundwater and stormwater runoff, especially in areas with a high water table or where the presence of seeps or springs provides a consistent source of water.

Pond construction may require a permit from the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), especially if a dam is necessary.5 The USACE website provides information on obtaining a permit and the SC Department of Health and Environmental Control (SCDHEC) Dams and Reservoirs website outlines review and permitting processes for dams. Dams cannot typically be placed in areas designated as jurisdictional Waters of the United States (WOTUS) without a permit and appropriate mitigation plans.6

“A permit will be required for any discharge of dredged or fill material into waters of the US associated with pond construction if the purpose is to convert a jurisdictional area into a use to which it was not previously subject, where the flow or circulation of waters may be impaired, or the reach of such waters reduced.” 6

Although most agricultural use ponds are exempt from the permit requirement, a producer must apply for the exemption.6 Knowledge of the watershed where the pond is to be built is essential, as most surface waters and wetland areas are classified as WOTUS. Please refer to the Land-Grant Press publication “How the 2020 Definition of WOTUS Affects Agricultural and Specialty Crop Producers” for more information on identifying surface waters and wetlands that constitute WOTUS.7

Many factors should be considered when deciding to use an existing pond or planning to build a pond for watering livestock. First, you must determine if the available water volume supports your expected number of animals. Table 1 lists the general volume of water needed by varied livestock species. Water volumes required can vary considerably due to environmental factors such as temperature and humidity in summer months, water quality, the age and stage of reproduction of the livestock, and the type of feed the animal is consuming.8

Table 1. Average water consumption volume for livestock.8,9

| Species | Average Water Consumption (gallons per day) |

Water Consumption Temperatures >80° F (gallons per day) |

| Beef cow | 6–15 | 20+ |

| Dairy cow | 15–30 | 30–40 |

| Sheep and goats | 2–3 | 3–4 |

| Horse | 10–15 | 20–25 |

| Swine | 6–8 | 8–12 |

Other factors to consider in planning the construction of a new pond include slope, size of the watershed, average rainfall, soil type, and the acreage and depth of the pond.9,10 Construction of a pond solely for livestock drinking is likely to be cost-prohibitive. Livestock owners should consult with a NRCS conservationist on cost-share programs for wells, spring development, or ram pumps16 to determine the option most feasible for watering livestock at their operation. A multi-use pond, such as one that also supplies water for irrigation, is typically more economically viable.

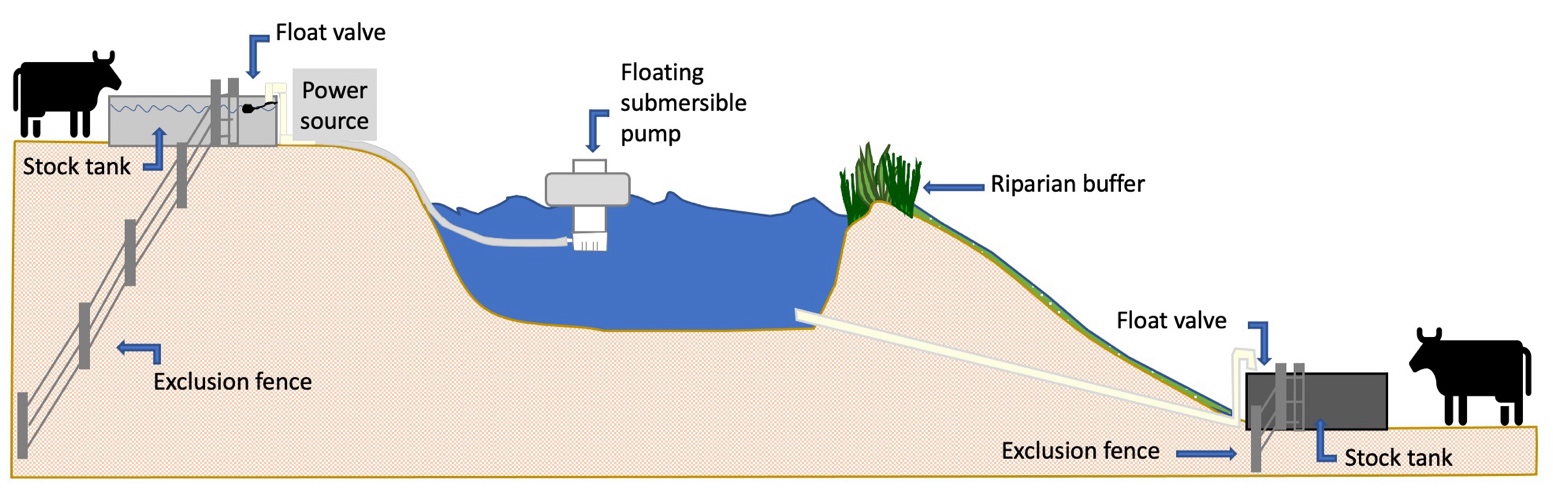

Livestock should be fenced out of any pond, with the water being directed or pumped into troughs (figure 1). Various off-pond livestock watering options can be used to provide water to livestock using an electric, solar-charged battery or a hydraulic energy source to pump the water to a watering tank.9,13,14,15,16 Gravity-based trough filling systems are suitable when the water source is elevated above the water trough. Generally, the water source needs to be at least five feet above the water trough for good flow.14

Figure 1. A conceptual image of various off-pond livestock watering options from pump-filled (left side) to gravity-fed (right side). Note that for any water source, exclusion fencing should be employed to deter livestock entry into drinking water. Image credit: adapted from The Cattle Site14 by Sarah White, Clemson University.

In some circumstances, allowing livestock limited access to the pond is acceptable if the impact on water quality is minimal (figure 2). Ideally, a gently sloped gravel ramp is constructed with geotextile fabric under the gravel, which will minimize erosion and environmental impact.14,17 Over time, sedimentation can reduce a pond’s water-holding capacity. Pond design specifications (depth) should be verified every few years to ensure the pond’s capacity is maintained to support livestock water needs. Please refer to PennState Extension’s Pond Measurements website for more information on measuring pond size and depth.

Figure 2. A fenced gravel ramp provides limited access to a pond for livestock. Image credit: John Jennings.1,13

Water Quality

Common water quality issues with an open pond for watering livestock include added nutrients and bacteria from animal waste. Increased sediment due to erosion can result from livestock entering and exiting the pond. Contaminants can affect animal health and production; therefore, restricting direct livestock access to the pond is recommended.18,19,20 Bacteria from animal waste can cause a variety of illnesses. These and other contaminants (e.g., salts, nitrates, and other minerals) in the pond water can reduce livestock water intake and consequently contribute to health and production issues.19 Other hazards to livestock that are minimized by exclusion from ponds are drownings, snake bites, and hoof problems.

Livestock exclusion reduces nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment loads and improves water quality in surface waters.21 Nutrient overloading can result in the growth of algae which can restrict water accessibility and palatability and potentially cause harmful algal blooms22 (rapid growth of blue-green algae or cyanobacteria) that might produce toxins harmful to livestock. Protecting water quality preserves clean water for livestock and supports healthy aquatic communities (from invertebrates to fish)23 and wildlife populations while protecting downstream water quality for other users. Periodically checking the quality of water in the pond is recommended so that it can be managed if problems arise. Clemson University’s Agricultural Service Laboratory website provides information about their water testing service. Testing for bacteria contamination can be done at various commercial laboratories. You can request a list of commercial environmental laboratories currently certified by SCDHEC by emailing labcerthelp@dhec.sc.gov or select a SCDHEC certified commercial laboratory from their Commercial Labs (CELMapp) website.

Upland Pasture Management

Buffer strips and riparian plantings around the pond can reduce the entry of nutrient and sediment contaminants into the pond and connected waterways (figure 1).24 Native plant selections for the different regions of South Carolina provide the best protection of the waterways since they tend to require fewer chemical inputs and, once established, reduce the potential for establishment of invasive plant species.25 The Clemson Cooperative Extension Carolina Yards Database allows users to make informed decision about selecting the best plant species for specific purposes.

Other considerations for protecting pond water quality include management practices used in the upland pastures. Poor pasture management often results in exposed soil that increases the potential for erosion. Some best management practices include (1) matching forages for the environment,26 soil type,27 and species of livestock28 and (2) managing stocking density to maintain an optimal residual forage cover. Research suggests that rotationally grazed pastures considerably reduce erosion compared to continuous grazing.29 Avoiding the use of pastureland near a pond’s edge during wet periods helps to preserve water quality.30 Pasture fertilization can also increase the rate of eutrophication (nutrient enrichment) of ponds and other surface waters. Following best management practices for fertilizer application by conducting soil tests and applying the correct fertilizer at the right rate and at the right time (e.g., plant growth stage, weather forecast) is important.31

Grazing systems designed to include the proper use of shade and the placement of water troughs to minimize the congregation of livestock will reduce sediment loss by minimizing exposed soil. Providing alternative water sources to an open pond reduces livestock time spent in the pond32 and increases production efficiency, especially when water troughs are placed no more than 800 feet apart.33 Strategic management of animal movement improves the uniformity of manure distribution34 and enhanced nutrient uptake and utilization by the forages and less runoff into the waterways.

Conclusion

Livestock water management plays an important role in protecting the health of the livestock, the ecology of the pond, and the water quality downstream. When considering using a pond for watering livestock, limit the herd size to the volume of water the pond can support and the pasture available near the pond. Additionally, fence the animals to restrict access to the water and use an off-pond watering system in conjunction with the pond to provide water to troughs. If planning to install a new pond, carefully consider all the options, including the possibility that adding a well may be the most economically and environmentally sound choice. Limiting livestock access to the pond protects water quality and reduces the potential for erosion. Careful management of fertilization timing and grazing regimes can also protect pond water quality and help to ensure the long-term utility of the pond.

References Cited

- Workman, S. (Department of Biosystems and Agricultural Engineering, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY) Limiting grazing cattle access to ponds to improve water quality, and water and feed intake. College Park (MD): Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE); 2005 Dec. Project Report OS03-008. https://projects.sare.org/project-reports/os03-008/.

- Biography of Hugh Hammond Bennett. Washington (DC): USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service. [accessed 2021 Dec 13]. https://web.archive.org/web/20071227103851/http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/about/history/bennett.html.

- Compton LV. Farm and ranch ponds. The Journal of Wildlife Management. 1952 Jul;16(3):238–242.

- Deal C, Edwards J, Pellmann N, Tuttle RW, Woodard D. Ponds—planning, design, construction. Mattinson MR, Glasscock LS, editors. Washington (DC): USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service; 1997. Agriculture Handbook 590. https://nrcspad.sc.egov.usda.gov/distributioncenter/pdf.aspx?productID=115.

- SCDNR. SCDNR Guidelines for Private Recreational Ponds. Columbia (SC): SC Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR); 2020 Mar. https://www.dnr.sc.gov/environmental/docs/private-ponds.pdf.

- US ACE. Charleston district agricultural irrigation pond exemption guide. Charleston (SC): US Army Corps of Engineers, Charleston District; 2012 [accessed 2021 Dec 13]. https://www.sac.usace.army.mil/Portals/43/docs/regulatory/Agricultural%20Irrigation%20Pond%20Exemption%20Guidance.pdf.

- White SA, Park D, Barrett A, Jones J. How the 2020 definition of WOTUS affects agricultural and specialty crop producers. Clemson (SC): Clemson Cooperative Extension, Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension; 2020 Jun. LGP 1075. https://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/how-the-2020-definition-of-wotus-affects-agricultural-and-specialty-crop- producers/.

- Meehan MA, Stokka G, Mostrom M. Livestock water requirements. Fargo (ND): North Dakota State University; 2021 Mar. AS 1763.

- Blocksome CE, Powee GM. Waterers and watering systems: a handbook for livestock owners and landowners. Manhattan (KS): Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service; 2006.

- Bowers S. Woodland ponds: a field guide. Corvallis (OR): Oregon State University, OSU Extension Service; 2015 Apr. EM 9104.

- Stone T. Pond construction and tax credits. Washington (DC): USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service; [accessed 2021 Mar 18]. https://www.clemson.edu/extension/carolinaclear/files/files%202/tstone_pondconstruct2.pdf.

- Vorhauer CF, Hamlett JM. GIS: a tool for siting farm ponds. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation. 1996 Sep; 51(5):434–438.

- Philipp D, Simon K. Water systems for cattle ponds. Little Rock (AR): University of Arkansas Cooperative Extension; 2015 Jul. FSA3128. https://www.uaex.edu/publications/pdf/FSA-3128.pdf.

- The Cattle Site. Remote pasture water systems for livestock. Alberta (Canada): Alberta Agriculture and Food and Agriculture Stewardship Division; 2008. [accessed 2021 Dec 13]. https://www.thecattlesite.com/articles/1308/remote-pasture- water-systems-for-livestock/.

- Marsh L. Pumping water from remote locations for livestock watering. Blacksburg (VA): Virginia Tech, Virginia Cooperative Extension; 2001. Publication 442-755. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/56803/442-755.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Smith WB. Homemade hydraulic ram pump for livestock water. Clemson (SC): Clemson University Cooperative Extension. Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension; 2019 Sep. LGP 1017. http://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/homemade-hydraulic-ram-pump-for-livestock-water/.

- Pond Watering Points. Poteau (OK): The Kerr Center for Sustainable Agriculture. [accessed 2021 Dec 13]; https://kerrcenter.com/conservation/stream-pond-protection/pond-watering-points/.

- Pfost DL, Charles DF, Casteel S. Water quality for livestock drinking. Colombia (MO): University of Missouri-Columbia, MU Extension; 2001 Feb. EQ38. https://extension.missouri.edu/media/wysiwyg/Extensiondata/Pub/pdf/envqual/eq0381.pdf.

- Brew MN, Carter J, Maddox MK. The impact of water quality on beef cattle health and performance. Gainesville (FL): University of Florida Extension; 2008 Nov. AN187.

- Hubbard RK, Newton GL, Hill GM. Water quality and the grazing animal. Journal of Animal Science. 2004;82(13):E255–E263.

- Line DE, Harman WA, Jennings GD, Thompson EJ, Osmond DL. Nonpoint-source pollutant load reductions associated with livestock exclusion. Journal of Environmental Quality. 2000;29(6):1882–1890. doi:10.2134/jeq2000.00472425002900060022x.

- Busari I, Sahoo D, Nix HB, Wallover CG, White SA, Sawyer CB. Introduction to harmful algal blooms (HABs) in South Carolina freshwater systems. Clemson (SC): Clemson Cooperative Extension, Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension; 2022 Jun. LGP 1146. https://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/introduction-to-harmful-algal-blooms-habs-in-south-carolina-freshwater-systems/.

- Knutson MG, Richardson WB, Reineke DM, Gray BR, Parmelee JR, Weick SE. Agricultural ponds support amphibian populations. Ecological Applications. 2004;14(3):669–684. doi:10.1890/02-5305.

- Lim TT, Edwards DR, Workman SR, Larson BT, Dunn L. Vegetated filter strip removal of cattle manure constituents in runoff. Transactions of the ASABE. 1998;41(5):1375–1381. doi:10.13031/2013.17311.

- Caflish M, Foster CR, White SA, Callahan K, Wallover CG, Powell B. Shorescaping freshwater shorelines. Clemson (SC): Clemson University Cooperative Extension Home & Garden Information Center. 2021 Sep; HGIC 1855. https://hgic.clemson.edu/factsheet/shorescaping-freshwater-shorelines/.

- Williamson JA, Hall M. Selecting the Best Forage Species. University Park (PA): The Pennsylvania State University, PennState Extension. 2017 Apr. https://extension.psu.edu/selecting-the-correct-forage-species.

- Forages.org. Ithaca (NY): Cornell University, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. http://www.forages.org/index.php/forage-species-information.

- Matches AG. Plant response to grazing: a review. Journal of Production Agriculture. 1992 Jan–Mar;5(1):1–7. doi:10.2134/jpa1992.0001.

- Gholamreza S, Yu B, Hossein G, Ciesiolka C A A, Rose C W. (2009) Effects of time-controlled grazing on runoff and sediment loss. Australian Journal of Soil Research. 2009;47,796–808. doi:10.1071/SR09032.

- Osmond DL, Butler DM, Rannells NR, Poore MH, Wossink A, Green JT. Grazing practices: a review of the literature. Raleigh (NC): North Carolina Agricultural Research Service; 2007 Apr. Technical Bulletin 325-W. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcs142p2_046597.pdf.

- Nutrient Pollution. The sources and solutions: agriculture. Washington (DC): United States Environmental Protection Agency; 2021 Nov. https://www.epa.gov/nutrientpollution/sources-and-solutions-agriculture.

- Godwin DC, Miner JR. The potential of off-stream livestock watering to reduce water quality impacts. Bioresource Technology. 1996 Dec;58(3):285–290. doi:10.1016/S0960-8524(96)00118-6.

- Gerrish J, Davis M. Water availability and distribution. Columbia (MO): University of Missouri. Missouri Grazing Manual; 1999. p. 81–88.

- Peterson PR, Gerrish JR. Grazing management affects manure distribution by beef cattle. American Forage and Grasslands Council: Proceedings. 1995 American Forage and Grasslands Council Annual Meeting; 1995 Mar 12–14; Lexington (KY). Berea (KY): American Forage and Grasslands Council. p. 170–174.

Additional Resources

Ponds in South Carolina (bit.ly/LGPpondsSC)

Recreational Ponds in South Carolina (bit.ly/RecPondsSC)

An Introduction to Stormwater Ponds in South Carolina (bit.ly/StormPondsSC)

An Introduction to Harmful Algal Blooms (bit.ly/3Qh0m31)

Testing Drinking Water (bit.ly/3X1rzdP)