There are three conventional methods of chemical site preparation using herbicides: backpack sprayers, sprayers on forestry equipment, and helicopters/fixed-wing aircraft. However, in recent years, agricultural drones have become increasingly popular for herbicide application. While drones (unmanned aerial vehicles; UAV) can perform common forestry tasks, meeting with the drone aerial applicator and collecting data for the herbicide application may look different. This publication familiarizes landowners and forestry professionals with chemical site preparation and seedling release via drones and explains what they should expect, from start to finish, from providers utilizing this technology.

Chemical Site Preparation

The final harvest of a forest stand exposes the seeds of previously shaded herbaceous and woody species that become competition for future seedlings. One common site preparation method is the use of chemical herbicides to control unwanted woody and herbaceous competition, allowing forest land managers to alleviate competition while minimizing soil disturbance and erosion (Figure 1; Peairs, 2020). To put the importance of site preparation into context, picture a circle with a 1-ft radius and a seedling in the middle. During the first couple years of that seedling’s life, the micro-environment surrounding that seedling has the most impact on its life in the long term (Kushla, 2017). It is during the first years of growth that seedlings encounter the most competition from undesirable species (Rayonier, 2022). Not only weeds and grass provide competition for planted seedlings; non-planted hardwood or softwood species that remain in a collection of seeds in the topsoil (known as the seed bank) can also compete. Most hardwood species can regenerate from coppice (stump/root sprouting), which increases the probability of establishing more dominant positions in the next stand after a disturbance (Vickers et al., 2011). Site preparation allows planted seedlings to get a head start on the next growth cycle of undesirables, allowing the target plant to achieve maximum growth potential. Without site preparation, the desired seedlings must compete for sunlight and nutrients, stunting their growth and, ultimately, leading to mortality.

Figure 1. Harvest Site that Received Partial Chemical Site Preparation (left). Image credit: Dr. Stephen Peairs, University of Tennessee Knoxville.

Seedling Release

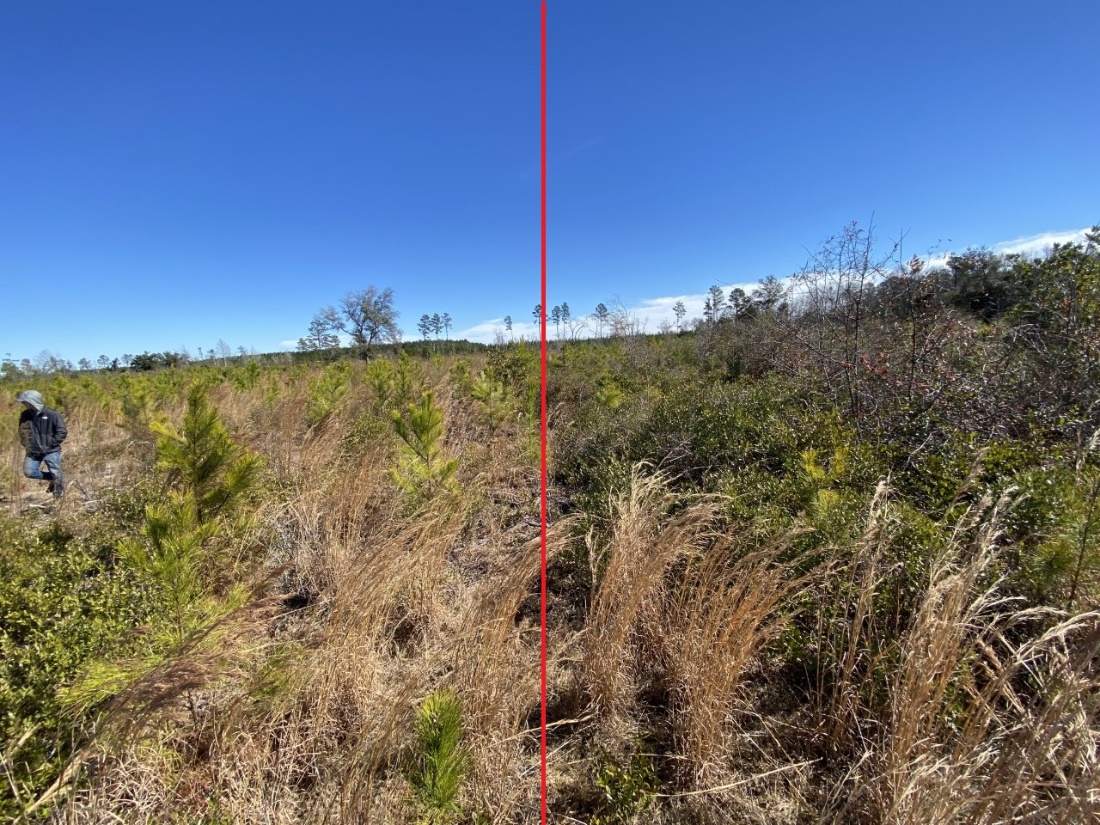

After planting and seeing seedlings move from year 0 (planting year) into year 1 and beyond, forest landowners must remain mindful that competition for their trees continues to germinate. Seed banks of grasses, weeds, and woody species can remain in the ground for years, and even decades (Quick, 1961). While prescribed fire is still the preferred method of controlling competition and understory vegetation (Quick, 1961), landowners may be unable to burn for up to five growing seasons. A growing season lasts from the last frost in the spring to the first frost in the fall. Depending on your location in South Carolina, the growing season can last from March 1 to November 15 in the Coastal Plain or April 15 to October 15 in the Upstate. Longleaf pines can survive controlled burns shortly after planting (while still in the grass stage), but loblolly pines grown commercially may need to grow for up to 5 years or until they are 3-4 in. in diameter or 15 ft tall (Cooperative Extension, 2020). Additionally, some pulpwood buyers may not purchase pine pulpwood with charred bark from prescribed fire, which may convince growers to delay prescribed burning until after the initial thinning. One method to limit competition to planted trees is to perform seedling releases (Figure 2). Seedling releases use a mixture of select herbicides (though fewer than are used for site preparation) tailored to the competitive species on a forest landowners’ site and safe for the desired trees. Refer to manufacturer label guidelines to select proper herbicides and avoid crop tree injury.

Figure 2. Site planted with Pine seedlings, some that received seedling release treatment (left) and some that did not (right). Image credit: Dr. Stephen Peairs, University of Tennessee Knoxville.

First Meeting with Drone Aerial Applicator

Landowners may be apprehensive about hiring a drone aerial applicator on their own or following another forester’s recommendation to use one at all. Using new technology on their property can make landowners apprehensive. This article’s authors aim to help landowners make the best decision on whether a drone aerial applicator is right for their property. While helicopter aerial applicators cover a large region of the Southeast every year and plan their spray route far in advance, drone aerial applicators are often local and readily available. The benefits to a landowner include a larger window of time in which the land can be sprayed because the spray crew is not just passing through (as is the case with helicopter applications). A drone aerial applicator typically meets the landowner or forester at the spray site for a site evaluation. This allows them to plan their spray mission and identify any obstructions they need to work around while spraying. This also allows the landowner to meet the applicator and ask any questions they have.

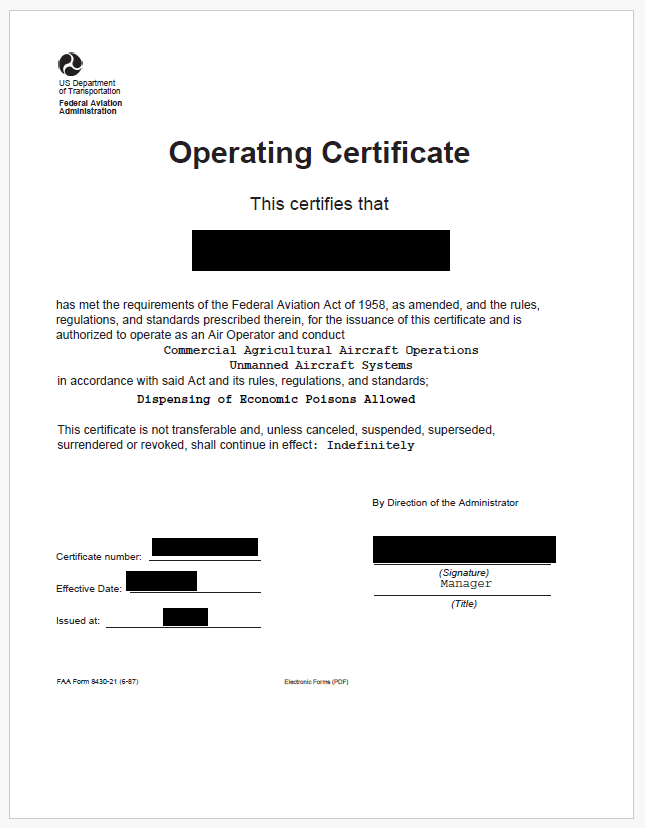

Forest landowners should ask specific questions during this initial meeting to ensure that the applicator has the proper permits and level of experience. Spray drone pilots undergo a series of licensing processes to ensure compliance with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The landowner should ask to see the applicator’s FAA Part 107 remote pilot certification (Figure 3; Small Unmanned Aircraft, 2016). The FAA Part 107 is essentially a driver’s license for drone pilots issued by the FAA after the pilot completes a 60-question knowledge exam; the certification is required for all monetarily compensated (commercial) pilots for their flight time. This license covers all drones that weigh 0.55-55 lbs. In addition to the FAA Part 107 certification, spray drone pilots have Section 44807 exemptions (Figure 4) that allow them to fly drones weighing more than 55 pounds, as some spray drones weigh over 200 lbs (Special Authority for Certain Unmanned Systems, 2025). A pilot also needs a Part 137 exemption (Figure 5) authorizing the dispensing of chemicals and agricultural products aerially (Agricultural Aircraft Operations, 2025). Proof of these three certifications and exemptions ensures that the pilot has done their due diligence in the eyes of the FAA and is licensed to fly and spray chemicals with a drone.

Figure 3. FAA Part 107 Drone Pilot License. Image credit: Carter Aerial Land Management, LLC.

Figure 4. Section 44807 Exemption to Fly Drones Over 55 lbs in Weight. Image credit: Carter Aerial Land Management, LLC.

Figure 5. FAA Part 137 Exemption to Apply Chemicals Aerially. Image credit: Carter Aerial Land Management, LLC.

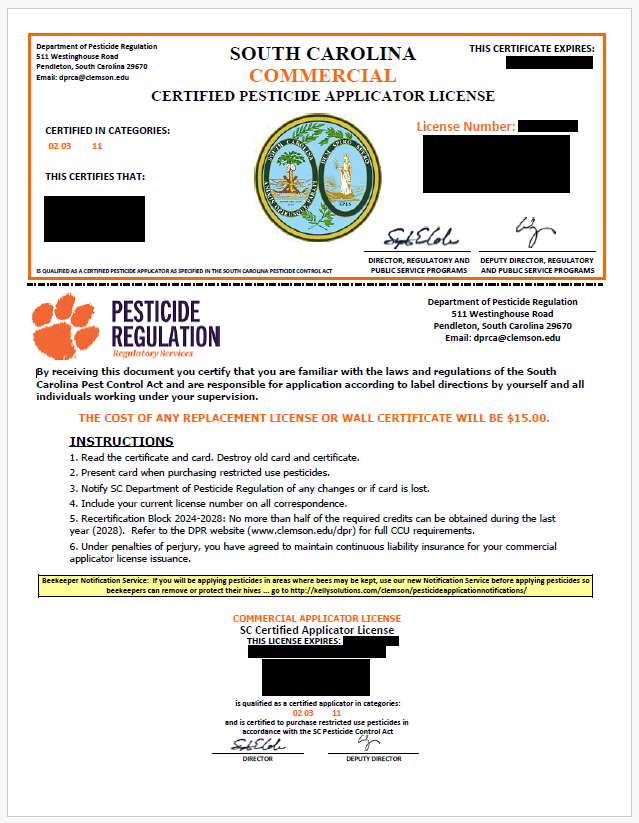

An aerial applicator operating in South Carolina must also have a South Carolina commercial pesticide applicator license (Figure 6; South Carolina Code of Laws). The state of South Carolina requires applicators to have a minimum of $50,000 of liability spray insurance to obtain a commercial license. When shown the license, check for certification in categories 02 (Forest Pest Control) and 11 (Aerial Application) on the lefthand side of the document to show proof that the applicator has passed the required tests for the state to apply chemicals aerially in a forest setting.

Figure 6. South Carolina Pesticide Applicator License. Note. Only the top part is relevant to landowners. The license must show certification in categories 02 and 11 for applicators to dispense herbicides aerially in forests. Image credit: Carter Aerial Land Management, LLC.

A drone aerial applicator’s first visit to a spray site allows the drone pilot to determine what types of woody and herbaceous competition are on site; with this information, they can develop an herbicide prescription tailored to the site. It is also possible that another company member prescribes the herbicides. In either scenario, the applicator on site should have a comprehensive understanding of plant resistance associated with herbicides labeled for forestry use.

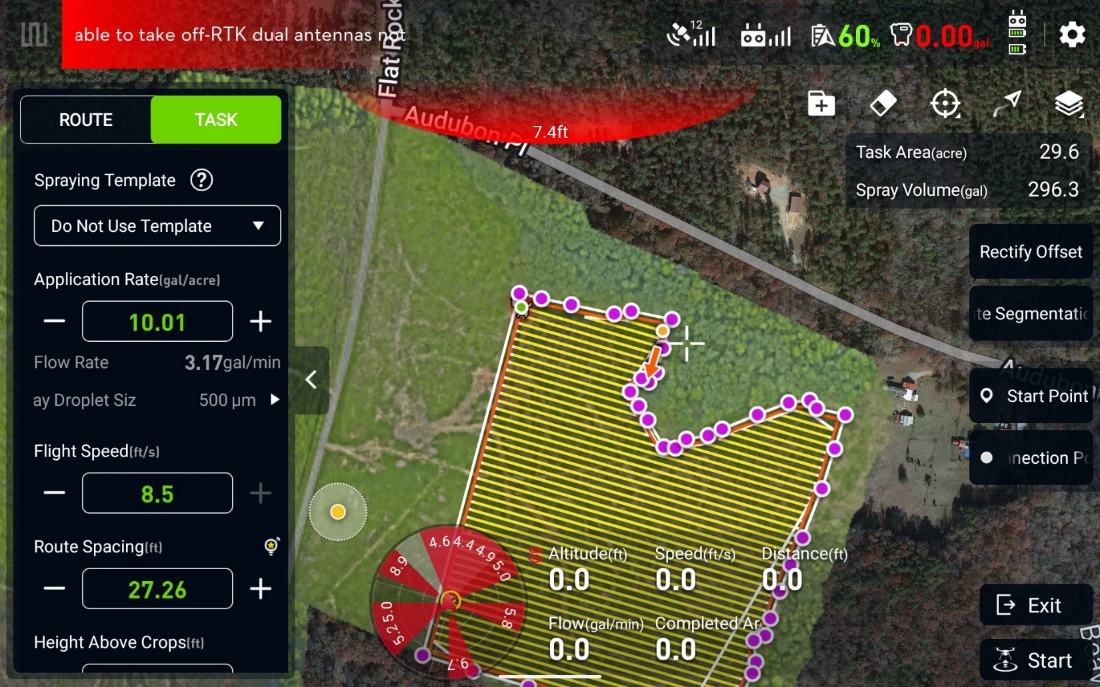

The controller of a large spray drone has a screen that displays a satellite view of the site and automatically maps the best flight paths for the drone (Figure 7). Satellite photos are a significant technological advancement, but they don’t always reflect the current conditions on the ground; they are only taken and updated periodically. This poses a problem for the drone aerial applicator: current satellite photos may not accurately reflect the spray site. To remedy this, some drone aerial applicators bring smaller drones during the initial site visit to create up-to-date maps of the spray site. The drone pilot can import that new map into the spray drone controller to give them an updated view of the site’s appearance from the sky. Since the drone aerial applicator is already making the map, the landowner may be able to ask for a copy of it for their records. Some drone aerial applicators charge extra for this, and some already include it with the spraying price.

Figure 7. Screenshot from the display of an Agras Spray Drone Controller. Image credit: Carter Aerial Land Management, LLC.

What to Expect on Spray Day

On the scheduled spraying day, the drone aerial applicator arrives with equipment that is a scaled-down version of what a helicopter may use (Figure 8). While not all applicators follow a standard protocol, there are many similarities. There is a clean water tank ranging in size from 275-1000 gallons and attached to a mixing tank ranging from 40-100 gallons. A 10-20 gallon per minute pump is the heart of the mixing operation, as it keeps the herbicide mixture in constant recirculation. This movement is paramount for certain herbicides, such as granular products. When needed, the pump can pull clean water into the mixing tank. Clean water or the herbicide mixture can be pumped into the drone.

An on-site generator makes spray operations possible in remote locations. Keep this in mind if the spray site is near houses, as the constant noise may disturb residents. The generator runs the pump (if not gas-powered), charges drone batteries, and provides power for other electrical needs. The drone aerial applicator performs a pre-flight inspection of the drone and equipment to ensure adequate operating conditions for safety and effectiveness. Pre-flight inspections also ensure that the drone and its spray nozzles work properly to deliver a calibrated volume of spray solution.

Figure 8. On-Site Drone Trailer. Note. This drone trailer contains a water tank (bottom, black), a smaller mixing tank (on top, white), and a wall-mounted pump. Image credit: Carter Aerial Land Management, LLC.

The drone aerial applicator often sets a geofence; this is an invisible perimeter that the applicator establishes using points on a map, and the drone can only spray within those limits. They also input other flight variables using the drone controller, including the rate of application (gallons per acre), spray width, flight speed, and flight height. The combination of these variables dictates how many flights the drone makes and how many gallons of solution the drone aerial applicator needs to mix in the tank. The drone typically flies autonomously during application, allowing for precise and efficient application. The drone often utilizes an advanced obstacle avoidance system that can detect objects as small as a power line in a spherical area surrounding the drone. On a forest site, standing snags or trees left behind after harvest also trigger the detection system. If the drone encounters an obstacle during flight, it stops movement and spraying and requires input from the drone aerial applicator to override the stop action. If such a delay occurs, the drone aerial applicator can resume the autonomous flight after overriding the action so that the drone continues spraying where it left off without spraying an area twice. The drone aerial applicator may charge more if the site has a significant presence of standing snags. Some obstacles require manual flight and spraying, making the process longer than the applicator expected.

Recordkeeping

Most drone aerial applicators have an app or website that helps them keep track of all previous flights. Landowners should keep detailed records of herbicide application flights to show which areas were sprayed and which were left untreated or “missed.” These records should include how many acres were sprayed. Drones record each flight as digital files that can be transferred to third-party record-keeping services (Figure 9). Every drone aerial applicator should provide the landowner with a map displaying the flight lines and the total rate of herbicide applied during the application. The report should also summarize the weather at the spray site during the herbicide application. If a landowner works with a cost-share program, the program requires this information to verify that the herbicide application was completed. The drone aerial applicator also needs to keep these records to track herbicide application for their business records. Since the drone generates reports for the drone aerial applicator, landowners should ask for a copy of the report for their personal records.

Figure 9. Post-spray report showing drone flight lines. Image credit: Carter Aerial Land Management, LLC.

Summary

Site preparation and seedling release are important forest management activities, and a drone aerial applicator may provide scheduling flexibility in the application of herbicides. Drone aerial applicators usually cover a local or regional area and travel within it when and where there is work. While spray drones in forestry may be a new option, the technology is safe and provides accurate application of herbicides. Drone aerial applicators are subject to multiple licensing processes that ensure that the drone pilots are qualified to perform the herbicide application with a drone.

References

- Agricultural Aircraft Operations. 14 C.F.R. § 137. (2025). https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/chapter-I/subchapter-G/part-137.

- Cooperative Extension. (2020, January 16). Using prescribed fire in loblolly pine stands. Prescribed Fire. https://prescribed-fire.extension.org/using-prescribed-fire-in-loblolly-pine-stands/.

- Kushla, J. D. (2017). Site preparation: The first step to regeneration (Publication #2823). Mississippi State University Extension.

- Peairs, S. (2020). Chemical release treatments for pine regeneration. Land-Grant Press, article 1090. http://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/chemical-release-treatments-for-pine-regeneration/.

- Pesticide Control Act. 46 South Carolina Code of Laws § 13 (1992). https://www.scstatehouse.gov/code/t46c013.php.

- Quick, C. R. (1961). How long can a seed remain alive. In A. Stefferud (Ed.), Seeds: the Yearbook of agriculture 1961. (pp. 94-99). U.S. Government Printing Office. https://www.fs.usda.gov/psw/publications/documents/misc/yoa1961_quick001.pdf.

- Rayonier. (2022, January 24). Site prep essential for southeastern forestry. https://www.rayonier.com/stories/site-prep-essential-for-southeastern-forestry/.

- Small Unmanned Aircraft. 14 C.F.R. § 107. (2016). https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/chapter-I/subchapter-F/part-107.

- Special Authority for Certain Unmanned Systems. 49 U.S.C. § 44807. (2025). https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title49-section44807&num=0&edition=prelim.

- Vickers, L. A., Fox, T. R., Loftis, D. L., & Boucugnani, D. A. (2011). Predicting forest regeneration in the Central Appalachians using the REGEN expert system. Journal of Sustainable Forestry, 30(8), 790-822. https://doi.org/10.1080/10549811.2011.577400

Additional Resources

- Hiesl, P., & Steele, J. (2023). Managing pine trees with a thinning. Land-Grant Press, article 1178. https://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/managing-pine-trees-with-a-thinning/

- Peairs, S. (2020). Chemical release treatments for pine regeneration. Land-Grant Press, article 1090. https://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/chemical-release-treatments-for-pine-regeneration/

- Peairs, S. (2020). Potential herbicide applications for hardwood stands. Land-Grant Press, article 1026. http://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/potential-herbicide-applications-for-hardwood-stands/

- Steele, J. (2019). Adequate site preparation can enhance productivity of new forest stands. Land-Grant Press, article 1039. https://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/adequate-site-preparation-can-enhance-productivity-of-new-forest-stands/

- Steele, J. (2020) Seedling selection guidelines for forest landowners. Land-Grant Press, article 1097. https://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/seedling-selection-guidelines-for-forest-landowners/