Healthy vegetation within buffer zones helps prevent erosion and intercepts sediment and pollutants (e.g., phosphorus) that can compromise water quality. The vegetation in buffer zones can include grasses, herbaceous perennials, shrubs, and trees. Once established, plants in riparian communities can develop thick root systems. Plant root systems contribute to improved soil health and bank stabilization and serve as a filter for sediments and pollutants that could wash into the pond otherwise. Proper management of the riparian buffer zones is needed to enhance stand longevity and support the sustainability of the ecosystem. This publication provides information on recommended plants for use in buffer zones of livestock ponds in three distinct regions (i.e., Upstate, Midlands, and Lowcountry) of South Carolina.

Introduction

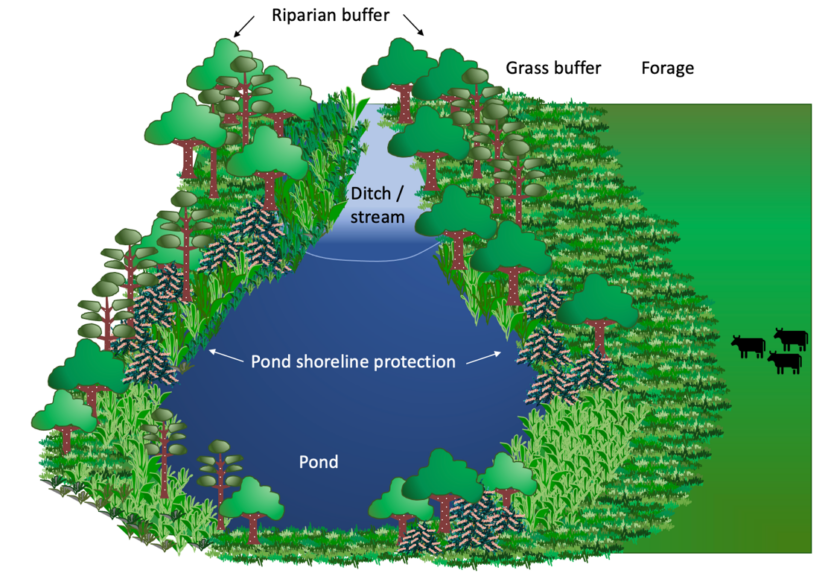

There is a growing concern over the impact of erosion and water quality. The plants grown in riparian (waterside) buffer zones can provide real benefits, such as intercepting soil and nutrient runoff, filtering sediments, decreasing erosion, and providing wildlife food, shelter, and habitat (figure 1).1 The vegetation can include grasses, trees, and shrubs that will vary depending on each operation’s location, goals, and economic feasibility.

Figure 1. Combination of land management techniques to reduce nutrient loading from the land into streams and ponds. Image credit: Sarah White, Clemson Extension.

For the buffer zones of livestock ponds, perennial plants with substantial growth and thick root systems, such as grasses, are recommended because they tolerate frequent defoliation and support soil health, water retention, and infiltration while persisting over time.2 A management plan (e.g., grazing and weed control events) is crucial for maintaining the vegetation and improving buffer zone longevity. When establishing a new buffer area, temporary exclusion of livestock and wildlife is necessary to allow seeds to germinate and small plants to grow until the stand is fully established before allowing livestock access.1 The exclusion time required varies with plant species, ecoregion, and weather conditions to favor quick establishment. The initial costs associated with establishing a new buffer site vary based on the plant species, planting method (e.g., seeds, sprigs), and soil amendments needed.

Livestock-Safe Buffer Vegetation for South Carolina Upstate, Midlands, and Lowcountry

Buffer Width

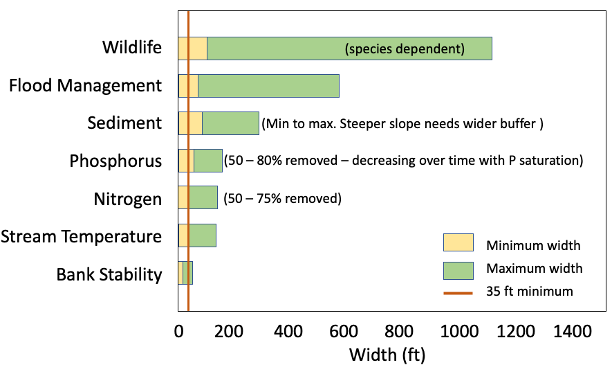

The width of the buffer zone needed depends upon water quality goals. If upland erosion is a concern, the recommended buffer width will be wider than if bank stability is the primary concern (figure 2). Thus, depending on the water quality issue being addressed, planting width suggestions will vary.

Figure 2. Suggested riparian buffer widths based on desired management endpoint. Image credit: Sarah White, Clemson University Adapted from Duppstadt and Penn.2

General Establishment and Management Recommendations

When choosing a plant species to be established in a buffer zone, several factors should be considered, including location, soil type, drainage, pH and fertility, and weather conditions. Often, a mixture of grasses, perennials, shrubs, and trees adapted to the area provides wildlife food and habitat and optimizes the ecosystem’s environmental benefits. Typically, riparian buffers that reduce livestock foraging and movement provide increased benefits. Hence, use of conventional forage species within the buffer is discouraged. Some commonly used forage species are non-native plants that could become invasive; thus, they should not be used within buffers to reduce the potential for seed dispersion by water.

Before planting, soil testing should be conducted. The Clemson University Agricultural Service Laboratory (Ag Service Lab) website has information on how to collect a sample and obtain soil testing services. Lime and fertilizer amendments should be applied based on the soil analysis report recommendations. Information on how to interpret a soil sample is available on the Ag Service Lab’s soil testing webpage, and your local Extension Agent can assist with additional questions. Contact information for staff at Extension county offices is available on the Clemson Cooperative Extension website.

When planting in a prepared seedbed, adequate weed control with application of a non-selective herbicide (labeled for use near a water body) and soil preparation should be conducted as a first step. Plant in the recommended planting window. If planting perennials, shrubs, or trees, consider the size of the material and duration for establishment—as smaller plant materials tend to establish more quickly within the landscape. If planting perennial grass species, use high-quality seed at the recommended seeding rate to optimize the chances for stand establishment success.

Amending soil pH and nutrient levels prior to planting is essential for establishing a successful riparian planting. Grass species included within riparian buffers are not intended to serve as a grazing source but rather as vegetation to protect and preserve the water quality of the pond. Fertilizer and pesticide applications adjacent to the water’s edge or within ten feet of the water’s edge should be minimized to reduce the potential for inadvertent negative impacts on water quality or livestock health.3

Perennials

Perennial species for use in riparian buffers often offer additional services to water quality protection that include reduced erosion, water shading, flood mitigation, and habitat preservation.4 Suggestions for perennial plant species to incorporate within riparian buffers are listed in table 1. Perennial plant species are typically planted closest to the pond edge, as most of those listed below are adapted to moist soils.4,5

Table 1. Livestock-safe perennial species suggested for use in riparian buffers, including mature size, features (bloom and wildlife attracted), and regions in South Carolina where the plant will successfully grow.

| Plant Species | Size * | Feature * | Upstate | Midlands | Lowcountry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conoclinium coelestinum

(blue mistflower) |

3’ H

3–4’ W |

Blue and purple flowers.

Butterflies, birds, and bees. |

x | x | x |

| Hibiscus coccineus

(scarlet rosemallow) |

3–8’ H

3–4’ W |

White, pink, and red flowers.

Butterflies and hummingbirds. |

x | x | |

| Hibiscus moscheutos

(swamp rosemallow) |

3–8’ H

3–4’ W |

White, pink, and red flowers.

Butterflies and hummingbirds. |

x | x | x |

| Iris virginica

(blue flag iris) |

1–3’ H

6–12” W |

Blue-purple flowers.

Hummingbirds and birds. |

x | x | x |

| Kosteletzskya virginica

(seashore mallow) |

5’ H

2–3’ W |

Pink, lavender, and white flowers.

Butterflies and hummingbirds. |

x | ||

| Rudbeckia fulgida

(black-eyed Susan) |

2–4’ H

18–24” W |

Yellow flowers.

Birds. |

x | x | x |

| Rudbeckia hirta var. angustifolia

(black-eyed Susan) |

3-4’ H

2–3’ W |

Yellow and orange flowers.

Butterflies and birds. |

x | x | x |

| Salvia coccinea

(scarlet sage) |

2’ H

3–6’ W |

Scarlet red flowers. Butterflies, hummingbirds, nectar-bees, and nectar insects. | x | x | |

| Salvia lyrata

(Lyre-leaf sage) |

1–2’ H

3–5’ W |

White, blue, and violet flowers.

Butterflies and hummingbirds. |

x | x | x |

| Solidago sempervirens

(seaside goldenrod) |

1–6’ H

1–2’ W |

Yellow flowers.

Butterflies, birds, and beneficial insects. |

x | ||

| Solidago canadensis

(tall goldenrod) |

3–6’ H

1–2’ W |

Yellow flowers.

Butterflies, nectar bees, and birds. |

x | x | x |

*Note: H = height, W = width; plant features as detailed in Reynolds et al.,3 Wildflower.org,4 and USDA Plants.5

Shrubs and Trees

Shrub and tree species used in riparian buffers can be either deciduous or evergreen. Selection of shrub or tree species depends upon the width of the riparian buffer desired, as tree and shrub species are typically incorporated into wider-spaced riparian buffers and can serve as a physical barrier to help discourage livestock movement toward the pond. Suggestions for shrub species for use within riparian buffers are listed in table 2. Tree species suggested for use in riparian buffers are listed in table 3. Some shrub and tree species tolerate “wet-feet” more than others; consult the Carolina Yards Plant Database or your local Extension Agent regarding plant selection.

Table 2. Livestock-safe shrub species suggested for use in riparian buffers, including mature size, features (bloom and wildlife attracted), and regions in South Carolina where the plant will successfully grow. Plants listed are deciduous unless otherwise noted in the Feature column.

| Plant Species | Size * | Feature * | Upstate | Midlands | Lowcountry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Callicarpa americana

(American beautyberry) |

Up to 8’ H

4–6’ W |

Showy purple berries in fall.

Fruit eaten by songbirds and small mammals, cattle browse twigs. |

X | x | x |

| Cephalanthus occidentalis

(buttonbush) |

3–4’ H

3–4’ H |

White, light-pink flowers.

Nectar bees, butterflies, and insects, hummingbirds, seeds consumed by waterfowl, ducks, and shorebirds. |

X | x | x |

| Clethra alnifolia

(sweet pepperbush) |

6-12’ H

4–6’ W |

Pink or white flowers. Thickets.

Bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds – nectar. Birds and mammals eat fruit. |

X | x | |

| Ilex vomitoria

(yaupon holly) |

4–12 (25)’ H

10–15’ W |

Evergreen, red berries. Thickets.

Berries consumed by songbirds, game birds, and small mammals. |

X | x | x |

| Itea virginica

(Virginia sweetspire) |

4–6’ H

4–6’ W |

White, pendulous flowers. Red fall leaves. Thickets.

Birds (cover) and nectar insects. |

X | x | x |

| Leucothoe axillaris

(coastal dog-hobble) |

2–4 (6)’ H

2–6’ W |

Evergreen. Showy white flowers.

Flowers: bees. |

X | x | |

| Leucothoe fontanesiana

(highland dog-hobble) |

3–6’ H

3–6’ W |

Evergreen. Showy white flowers.

Flowers: bees. |

X | ||

| Morella cerifera

(wax myrtle) |

6–12’ H

6–12’ W |

Evergreen. Fruits eaten by birds.

Flowers: birds and butterflies. |

X | x | x |

| Osmanthus americanus

(American olive) |

15–30’ H

20–30’ W |

Evergreen. Fragrant, non-showy flowers. Dark-blue fruit. | X | x |

*Note: H = height, W = width; plant features as detailed in Reynolds et al.,3 Wildflower.org,4 and USDA Plants.5

Table 3. Livestock-safe tree species suggested for use in riparian buffers, including mature size, features (bloom and wildlife attracted), and regions in South Carolina where the plant will successfully grow. Plants listed are deciduous unless otherwise noted in the Feature column.

| Plant Species | Size * | Feature * | Upstate | Midlands | Lowcountry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acer rubrum

(red maple) |

40–70’ H

30–50’ W |

Red flowers, fruits, and leaves. Food for birds, insects, and small mammals. | X | x | x |

| Betula nigra

(river birch) |

40–70’ H

40–60’ W |

Seeds eaten by grouse, turkeys, small birds, and rodents. | X | x | x |

| Cornus florida

(dogwood) |

15–30’ H

15–30’ W |

White flowers and red berries. Fruits attractive to birds and small mammals. Flowers support native bees. | X | x | x |

| Juniperus virginiana

(eastern red cedar) |

30–65’ H

8–25’ W |

Evergreen. Berries attractive to birds and small mammals. Attracts birds and butterflies. | X | x | x |

| Magnolia virginiana

(sweetbay magnolia) |

10–35’ H

10–35’ W |

Semi-evergreen. Fragrant cream-white flowers. Red seeds. Nectar moths, beetles. Attracts birds. | X | x | x |

| Pinus elliottii

(slash pine) |

80-100’ H

35–50’ W |

Evergreen. Seeds food source for gray and fox squirrels, and wild turkey. | X | ||

| Pinus taeda

(loblolly pine) |

40–90’ H

20–40’ W |

Evergreen. Attracts birds and butterflies. Seeds for small mammals and granivorous birds. Nesting site. | X | x | x |

| Pinus palustris

(longleaf pine) |

100–120’ H

40–60’W |

Evergreen. Attracts birds and butterflies. Seeds for small mammals and granivorous birds. Nesting site. | X | x | |

| Taxodium distichum

(bald cypress) |

50–70’ H

20–45’ W |

Copper foliage in fall. Cover for nesting birds. Seeds for birds and mammals. | X | x | x |

*Note: H = height, W = width; plant features as detailed in Reynolds et al.,3 Wildflower.org,4 and USDA Plants.5

Native Grasses

Native warm-season grasses are adapted to the southeast region and, for the most part, can be used throughout the state of South Carolina. The most commonly used native grasses are listed in table 4. Some native grasses may occur voluntarily in some areas, and usually, they break dormancy in early April.6 Once established, their growth is more concentrated from mid-May through mid-summer, then growth slows in late summer until they become dormant in October. Generally, native warm-season grasses are drought tolerant, and their natural occurrence makes them good options for use. However, the stand establishment can be more challenging than other planted forages due to smaller seeds and slower establishment, leading to weed competition. This may require increased weed control management until the stand is established. Overall, native grasses typically have lower forage quality than other planted grasses for livestock production, and they can strengthen environmental benefits within these ecosystems.

Table 4. Livestock-safe native grass species suggested for use in riparian buffers, including mature size, features (bloom and wildlife attracted), and whether they can be used as alternate forage.

| Plant Species | Size * | Feature * | Forage? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andropogon gerardii

(big bluestem) |

4–6’ H

2–3’ W |

Color-changing foliage (gray-green to red shades). Birds and mammals use for nesting and cover. Larval host for butterflies and moths. | X |

| Andropogon glomeratus

(bushy bluestem) |

3–6’ H

2–3’ W |

Feathery flowers, robust, non-lodging foliage. Small birds eat seeds. Small mammals eat foliage and use as cover. | X |

| Chasmanthium latifolium

(river oats) |

2–5’ H

1–2½’ W |

Graceful seed heads. Seeds eaten by birds and mammals. Leaves nesting materials for birds. Larval host for butterflies. | |

| Muhlenbergia capillaris

(muhly grass) |

2–3’ H

2–3’W |

Bright-pink wispy flowers in fall.

Habitat for beneficial insects and beetles. |

|

| Panicum virgatum

(switchgrass) |

3-6’ H

2–3’ W |

Nesting and fall or winter cover for birds and mammals. Seeds for songbirds and game birds. Larval host for skippers. | X |

| Schizachyrium scoparium

(little bluestem) |

1–3’ H

1½–2’ W |

Colorful, clumping foliage bears wispy small flowers. Seeds consumed by small mammals and birds. Foliage excellent nesting and roosting habitat. | X |

| Sorghastrum nutans

(Indiangrass) |

3–5’ H

1–2’ W |

Nesting material/structure for native bees. Larval host for skipper. Seeds eaten by birds and small mammals. | X |

| Tripsacum dactyloides

(eastern gamagrass) |

4–8’ H

4–6x’ W |

Clumping and upright. Seeds enjoyed by deer and birds. Stalks used as cover and nesting sites. Larval host skipper. | X |

*Note: H = height, W = width; plant features as detailed in Wildflower.org,4 and USDA Plants5

Poisoning of Livestock

Poisonous plants contain toxic compounds that can reduce performance (e.g., milk production), compromise health, or kill livestock animals when consumed. The severity of poisoning is related to the quantity eaten and concentration of toxic compounds, animal species and category (e.g., age, size), and overall animal health.6 Some of the main factors associated with animals consuming poisonous plants include

- Availability of seasonal species during periods of forage shortage (early spring, fall, or dry periods)

- Accumulation of toxins during prolonged droughts

- Animals browsing new areas or household waste (e.g., goats browsing ornamental plants that may contain toxic compounds

Several ornamental plants and weeds are among the poisonous plants for livestock. Shrub and tree species to avoid include those whose leaves or fruit could be poisonous to livestock, such as black walnut (Juglans nigra), buckeye (Aesculus spp.), wild cherry (Prunus serotina), choke cherry (Prunus virginiana), Chinaberry (Melia azedarach), elderberry (Sambucus spp.), milkweed species (Asclepias spp.), mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia), nandina (Nandina domestica), oleander (Nerium oleander), rhododendron (Rhododendron spp.).7 Perennial species to avoid are those whose leaves, seeds, or fruit could be poisonous to livestock, these include black nightshade (Solanum nigrum), horsenettle (Solanum carolinense), baccharis (Bacharis spp.), Carolina jessamine (Gelsemium sempervirens), lantana (Lantana camara), scotchbroom (Cytisus scoparius).7

Symptoms of plant poisoning vary from mild to severe and include weakness, nausea, salivation, vomiting, erratic behavior, convulsion, and death.8 The management plan for pastures and the buffer zones, whether mowed or grazed, should avoid overgrazing and include weed control and fertilization management. Healthy forage stands can compete with and suppress weeds, including poisonous plants. For pastures, rotational grazing helps provide proper resting time for plants to replenish energy reserves and support stand longevity. A similar management plan should be established for buffer zones to allow them to rest and maintain the recommended stubble height after each defoliation.

Sustainability

Riparian buffers are essential components of water quality protection, whether the buffers abut cropland, pastures, or developed areas. The plant communities within riparian buffers can offer ecosystem services beyond water quality protection alone. Each plant type, whether tree, shrub, herbaceous perennial, or grass, is essential in delivering ecosystem services, and the management practices directly affect their ability to provide ecosystem services.9,10 Each plant serves to help

- Decrease erosion and improve soil chemical and physical characteristics,

- filter sediment and reduce nutrient runoff,1,11 and

- provide habitat, shelter, and food to aquatic and upland wildlife.12

When grazing the edge of the buffer zone closest to the pasture, a defoliation management plan should follow recommended stubble height and resting periods to allow plants to recover energy reserves and root systems for persisting over time.

Well-established plant root systems can reduce soil and nutrient losses in buffer zones. Thus, soils under riparian buffer stand support carbon sequestration due to the input of organic carbon13-16 Soil organic matter is a crucial component of soil health, affecting its biological, chemical, and physical properties and supporting nutrient cycling within the ecosystem.15 For buffer zones, well-established plant stands can also contribute to protecting the soil around the water source and avoid issues with water quality due to treading by livestock and wildlife.

Conclusion

Several types of plants can be integrated into buffer zones around livestock ponds. Trees and shrubs provide shade and a visual barrier, helping to limit access to the pond, while perennial species (grasses and ornamental perennials) are recommended for their ability to persist over time and establish thick root systems that improve soil health. Perennial grasses can also tolerate frequent defoliation, so they should be used at the outer edge of the riparian buffer closest to the pasture. Healthy vegetated buffers help with filtering sediments, excess nutrients, and pollutants that could otherwise compromise the pond water quality for livestock.

References Cited

- Webber DF, Mickelson SK, Ahmed SI, Russell JR, Powers WJ, Schultz RC, Kovar JL. Livestock grazing and vegetative filter strip buffer effects on runoff sediment, nitrate, and phosphorus losses. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation. 2010 Jan 1;65(1):34–41.

- Duppstadt L, Rhea D. Riparian buffers for field crops, hay, and pastures. University Park (PA): Penn State Extension. 2021 [accessed 2023 Feb 21]. https://extension.psu.edu/riparian-buffers-for-field-crops-hay-and-pastures.

- Reynolds W, Ohlandt K, Savereno L. Backyards buffers for the South Carolina Lowcountry. Columbia (SC): South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control. Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management; 2007 [accessed 2023 Feb 21]. https://scdhec.gov/sites/default/files/docs/HomeAndEnvironment/Docs/backyard_buffers.pdf.

- Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Plant Database. Austin (TX): University of Texas at Austin; 2023 [accessed 2023 Feb 23]. https://www.wildflower.org/plants/.

- United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. The PLANTS Database. Greensboro (NC): National Plant Data Team; 2023 [accessed 2023 Feb 23]. https://plants.usda.gov/.

- Keiser P. Native grass forages for the eastern US. Knoxville (TN): The University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture; 2022. PB 1893. 92 p.

- Guide to Poisonous Plants: Horse chestnut. Ft. Collins (CO): Colorado State University; 2022 [accessed 2023 Feb 23]. https://csuvth.colostate.edu/poisonous_plants/Plants/Details/51.

- Silva LS, Dillard SL, Mullenix MK, Wallau M, Vasco C, Tucker JJ, Keishmer K, Russell D, Kelley K, Runge M, Gamble A, Prasad R, Elmore M, Burns M, Stanford K, Niyigena V, Wickens C, Sawadgo W, Heaton C. Concepts and research-based guidelines for forage-livestock systems in the Southeast region. College Park (MD); USDA (US Department of Agriculture), SARE (Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education; 2022 [accessed 2023 Feb 23]. SPDP21-04. 127 p. https://projects.sare.org/wp-content/uploads/Book_SARE.pdf.

- Conant RT, Cerri CE, Osborne BB, Paustian K. Grassland management impacts on soil carbon stocks: a new synthesis. Ecological Applications. 2017 Mar;27(2):662–668.

- Ammann C, Flechard CR, Leifeld J, Neftel A, Fuhrer J. The carbon budget of newly established temperate grassland depends on management intensity. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 2007 Jun 1;121(1-2):5–20.

- Cole LJ, Stockan J, Helliwell R. Managing riparian buffer strips to optimise ecosystem services: a review. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 2020 Jul 1;296:106891.

- DeCecco JA, Brittingham MC. Riparian buffers for wildlife. University Park (PA): Penn State Extension; 2017 [accessed 2023 Feb 21]. https://extension.psu.edu/riparian-buffers-for-wildlife.

- Sokol NW, Kuebbing SE, Karlsen‐Ayala E, Bradford MA. Evidence for the primacy of living root inputs, not root or shoot litter, in forming soil organic carbon. New Phytologist. 2019 Jan;221(1):233–46.

- D’Ottavio P, Francioni M, Trozzo L, Sedić E, Budimir K, Avanzolini P, Trombetta MF, Porqueddu C, Santilocchi R, Toderi M. Trends and approaches in the analysis of ecosystem services provided by grazing systems: a review. Grass and Forage Science. 2018 Mar;73(1):15–25.

- Conant RT, Cerri CE, Osborne BB, Paustian K. Grassland management impacts on soil carbon stocks: a new synthesis. Ecological Applications. 2017 Mar;27(2):662–668.

- Sollenberger LE, Kohmann MM, Dubeux Jr JC, Silveira ML. Grassland management affects delivery of regulating and supporting ecosystem services. Crop Science. 2019 Mar;59(2):441–459.

Additional resources

White SA, Beecher L, Davis RH, Nix HB, Sahoo D, Scaroni AE, Wallover CG. Ponds in South Carolina. Clemson (SC): Clemson Cooperative Extension, Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension; 2021 Jul. LGP 1114. https://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/ponds-in-south-carolina/.

Davis RH, Nix HB, White SA, Smith WB. Livestock ponds in South Carolina. Clemson (SC): Clemson Cooperative Extension, Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension; 2023 Jan. LGP 1156. https://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/livestock-ponds-in-south-carolina/.

Nix HB, Beecher L, Davis RH. Recreational ponds in South Carolina. Clemson (SC): Clemson Cooperative Extension, Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension; 2021 Oct. LGP 1125. https://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/recreational-ponds-in-south-carolina.

Scaroni AE, Sahoo D, Wallover CG. An introduction to stormwater ponds in South Carolina. Clemson (SC): Clemson Cooperative Extension, Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension; 2021 Aug. LGP 1119. https://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/an-introduction-to-stormwater-ponds-in-south-carolina.

Nix HB, Lunt S, Davis RH. Pond weeds: causes, prevention, and treatment options. Clemson (SC): Clemson Cooperative Extension, Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension; 2021 Dec. LGP 1126. https://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/pond-weeds-causes-prevention-and-treatment-options.

Nix HB, McCall Jr EC, Chastain JE. Pond maintenance: dredging. Clemson (SC): Clemson Cooperative Extension, Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension; 2022 Oct. LGP 1153. https://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/pond-maintenance-dredging.

Wallover CG. Cyanobacteria: understanding blue-green algae’s impact on our shared waterways. Clemson (SC): Clemson Cooperative Extension, Home & Garden Information Center (HGIC); 2015 Aug 26. Factsheet HGIC 1858. https://hgic.clemson.edu/factsheet/cyanobacteria-understanding-blue-green-algaes-impact-on-our-shared-waterways/.