Healthy hooves are the foundation of a healthy horse. This publication gives an overview of basic hoof anatomy, hoof care practices, and common ailments for horse owners to best maintain the health and functionality of their horses’ feet.

Care and Trimming

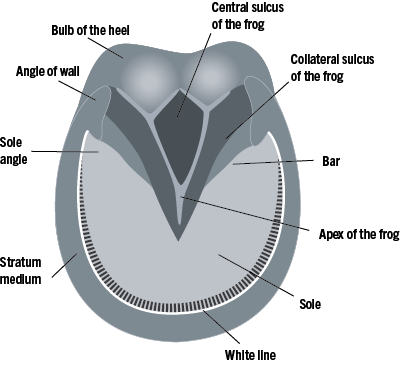

Maintaining the hoof in a condition that does not inhibit the horse’s gait requires some training and an understanding of hoof growth and anatomy. This section is only an overview of the anatomy and process; more detailed instruction and demonstration is required to provide the necessary education on how to correctly trim a hoof. Figure 1 shows components of the hoof capsule including the straturn medium (or hoof wall), sole, frog, and bulb of the heel.

The straturn medium or hoof wall must be kept as a smooth weight-bearing surface; therefore, one-fourth to three-eighth inch of monthly growth will need to be trimmed away or, if it is wearing too rapidly, protected with a set of shoes or boots.1 The sole also will need to be trimmed periodically so that it remains below the weight-bearing surfaces but never thin enough to bruise easily. The outer surface of the hoof wall is covered by a wax-like material that seals and helps conserve moisture within the hoof, and this protective surface should not be removed when the hoof is trimmed.

Several factors affect the rate at which the hoof regrows, and depending on these factors, the hoof may need to be trimmed anywhere between a 5- to 12-week interval.1 Factors include

- Age of the horse – hooves of younger horses grow faster than older horses.

- Climatic conditions – hoof growth slows during colder winter months.

- Nutrition – horses with nutritional deficiencies will grow a weaker, less flexible hoof than those with an adequate nutrient supply.

- Terrain and/or housing conditions – more natural wear on the hoof will occur in horses kept in rocky or hard-terrain pastures compared to softly bedded stalls or paddocks with sandier soil.

- Exercise – exercise promotes healthy hoof growth.

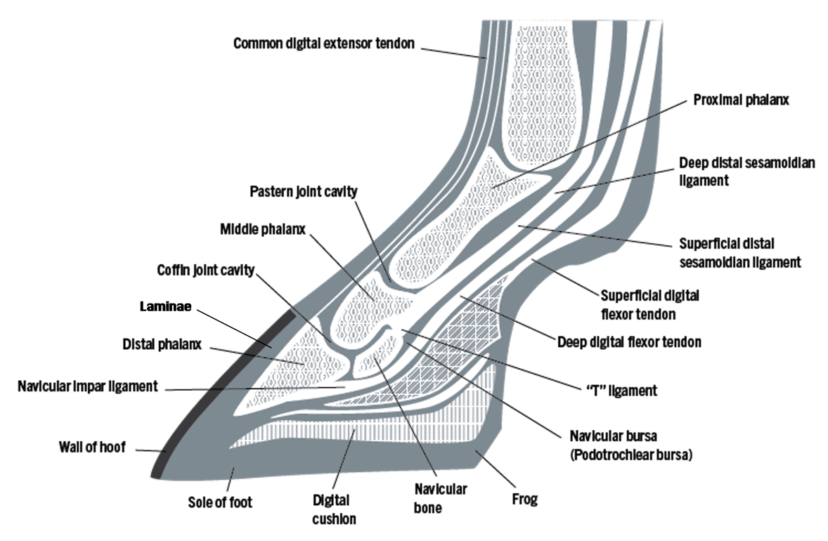

For many recreational horses, keeping the hoof trimmed and level is adequate. They usually require shoes or boots only when horses are being used heavily or ridden in rocky terrain. Some horses need shoes other than flat shoes to correct problems or alter natural movement. Trimming the hoof requires skill and three primary tools: a rasp, nippers, and hoof knife. The hoof knife is used to remove some of the sole and trim the frog (figure 2). The sole is concave to the ground. The elastic wedge-shaped mass under the heel is known as the frog (figure 1) and is an integral part of the horse’s shock absorption system. The nippers are used to cut away the hoof wall (figure 3). More of the wall is removed at the toe than the heel. The rasp is then used to smooth the cuts and level the surface (figure 4). Nailing on shoes requires considerably more skill and practice under the watchful eyes of a trained farrier.

Common Hoof Ailments

Thrush

Thrush is a common infection of the hoof and occurs in the frog cleft (central sulcus) and collateral grooves or sulcus, which run along each side of the frog (figure 1).2 Thrush has a characteristic odor (rotting and foul) and the presence of black or gray discharge/decaying tissue. The frog will be softer, sometimes tender to touch, and prone to tears. The infection can be caused by wet and dirty conditions that can also cause abscesses; however, the infection does not penetrate the hoof wall. Severe thrush can cause a deepening of the central cleft between one-fourth and one-half inch, and a puss or bloody discharge occurs when a hoof pick is used to clean this area.

Simple but persistent treatment is necessary and involves the delivery of any disinfectant deep into the sulcus and can be done one of two ways. The first option involves soaking a small cotton round with a disinfectant, such as those containing copper sulfate or povidone-iodine and wedging it into the central cleft with a hoof pick. By pushing the cotton all the way into the central sulcus, the medication can reach and act on the deepest part of the infected frog. This treatment should be done daily for seven days. If it is not healed within one week after the seven days of treatment is completed, it should be repeated until healed. The second option utilizes topical antibiotic gel that is typically used to treat mastitis in cattle. The long application tip for pushing the gel up into the teat makes it easy to ensure the medication reaches the bottom of the frog cleft. Treatment should be administered until the infection has completely healed and the depth of the frog cleft has returned to normal.

Sole or Wall Abscess

An abscess is an infection between laminae and the hoof wall or sole. The infection originates when bacteria is introduced through the sole, often through trauma, a blemish, or softening. Trauma can occur if the horse steps on something hard (e.g., a nail or piece of glass) when the hoof capsule is softened, most often during wet weather conditions, or when standing in wet, dirty stalls for prolonged periods. An abscess is a common cause of sudden onset lameness. The pain experienced by the horse is due to the abscess pressure under the hoof wall. Often, heat can also be felt in the hoof, and the pulse taken at the pastern (figure 5) will be stronger and more easily detected when there is an infection.

Treatment focuses on drawing the infection to the sole surface, often by soaking the hoof so that it can drain. A veterinarian may also pare a small hole to relieve the pressure and allow drainage if they can locate the site of infection. If left untreated, the abscess can migrate up the inside of the hoof wall and rupture near the coronary band (where the hairline meets the foot capsule) at the top of the hoof wall. Although pain is almost instantly relieved after the abscess has ruptured, one that ruptures along the coronary band is harder to flush and treat further.

Laminitis (Founder)

Laminitis is a systemic disease that manifests in the hoof when the laminae (tissue) between the hoof wall and distal phalanx become inflamed and weaken.3 In severe cases, the laminae separate from the distal phalanx or coffin bone, causing loss of the hoof’s mechanical integrity and significant pain and lameness.4 Mild episodes of laminitis can be confused with sole bruising, arthritis, or hoof soreness following trimming or shoeing.

In the case of laminitis, the focus should remain on prevention rather than treatment. Since one proposed mechanism involves digestive and metabolic disturbances by the overconsumption of carbohydrates from grain or lush pasture grasses, proper feeding management should always be followed. Care should be taken to avoid excessive grain intake, which could overload a horse’s digestive system with rapidly fermentable carbohydrates. The acidic conditions caused by excessive microbial fermentation are responsible for systemic inflammation and resulting laminitis. The same care should be taken when introducing horses to a new diet or pasture to avoid digestive disturbances. Once laminitis is diagnosed by your veterinarian, treatment involves careful and coordinated therapies between your veterinarian and farrier to prevent further damage to the laminae.

These three common equine hoof conditions can be prevented or treated with proper management; however, several others conditions often have similar symptoms. It is always best to get a diagnosis from a veterinarian or qualified farrier when hoof problems arise to ensure the most effective treatment.

References Cited

- Butler DK. Principles of horseshoeing II. Butler Publishing. 1985.

- Belknap JK. Disorders of the foot in horses. In: Winter AL, editor. Merck Veterinary Manual. Kenilworth (NJ): Merck & Co., Inc.; 2021. https://www.merckvetmanual.com/musculoskeletal-system/lameness-in-horses/disorders-of-the-foot-in-horses.

- Frandson RD, Wilke WL, Fails, AD. Anatomy and physiology of farm animals. 7 ed. Hoboken (NJ): Wiley-Blackwell; 2009.

- Pollitt CC. Equine laminitis. Clinical Techniques in Equine Practice. 2004 Mar;3(1):34-44.

References Consulted

Adapted from Horses: hoof care. Clemson Cooperative Extension Fact Sheet. March 1985.