White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) are the most hunted and economically important game species in North America.1 Deer population management is important to maintain the health of deer herds and to protect their habitats from the effects of overpopulation. In order to effectively manage deer, it is important to have metrics that provide evidence of success towards specific management objectives. Metrics such as body weight, antler development, and reproductive rates are most meaningful when paired with the age of the deer to provide context for each metric. There are two widely used techniques for aging white-tailed deer: (1) tooth replacement and wear and (2) cementum annuli. The tooth replacement and wear technique may be utilized in the field, whereas the cementum annuli technique requires the collection of teeth and laboratory analysis.

Tooth Replacement and Wear versus Cementum Annuli

The most common technique for aging white-tailed deer is tooth replacement and wear, developed by C.W. Severinghaus in 1949.2 Tooth eruption and replacement of temporary teeth by permanent teeth can indicate the age of the deer up to 1.5 years old. After 1.5-years-old tooth wear is used to determine the age. Tooth wear criteria use a series of comparisons of tooth characteristics to assign the age and will be explained later in the paper. However, this technique for aging deer may suffer inaccuracies due to variation in nutrition, amount of grit on vegetation, and soil types.3 For instance, a white-tailed deer that feeds primarily on clover in loamy soils, may have less tooth wear than a deer that feeds primarily on twigs during the winter in the northeastern United States. Although undocumented, genetics and individual health may also contribute to variation.

The cementum annuli technique uses a cross section of a primary incisor (two front teeth) of the deer to count the number of “rings.” This technique rests on the principle that a white-tailed deer will have annual growth “rings,” similar to growth rings of a tree, which indicate age.4,5 This technique is assumed to be more accurate than the tooth replacement and wear technique since the age estimation is conducted and assigned in a laboratory setting. However, evidence suggests that this technique may not be any more or less accurate than using the tooth replacement and wear technique.6,7,8

It appears that geographic region may dictate which technique is more appropriate. For example, in a Mississippi study, there were significant differences between the ages assigned using the two techniques (table 1). Deer that were aged by the Severinghaus technique as 1.5 years old were aged as 1.5 years old only 17.3% of the time by the cementum annuli technique. For a 1.5-year-old deer, age determination by the Severinghaus technique is reliable because of tooth characteristics and replacement patterns. In the same study, five fawn incisors were collected and submitted for aging using the cementum annuli technique, and all were aged as 1.5 years old. Again, the age of fawns was known due to tooth replacement and not subjective, as in the case of older deer. Thus, the cementum annuli technique overestimated the age for fawns and 1.5-year-old deer almost 83% of the time.7

Table 1. Comparison of age determinations between cementum annuli and tooth replacement and wear techniques in Mississippi.7

| Wear/Replacement Technique | Number Aged | Over-aged by Cementum Annuli | Under-aged by Cementum Annuli | Aged the same by Cementum Annuli |

| All age classes | 211 | 67.9% | 7.2% | 24.9% |

| Yearlings (1.5-years-old) | 52 | 82.7% | 0.0% | 17.3% |

| Fawns | 5 | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

In a Texas study, twenty-five known-aged deer incisors were collected and submitted for cementum annuli aging. Of the twenty-five submitted, the cementum annuli technique correctly aged four (16%) of the deer. Of the deer incorrectly aged, 90.5% were assigned ages as younger than the known ages. Another objective of this study was to determine the efficiency in correctly assigning age classes by wildlife biologists. Biologists were given 363 known-aged jawbones, and they correctly assigned ages 66.7% of the time using the Severinghaus technique. However, when the biologists incorrectly aged a deer, they tended to overestimate the age, whereas the cementum annuli technique underestimated the ages. 6

In a more recent study, thirty-four white-tailed deer biologists were asked to assign ages to known-age jawbones from Oklahoma using the Severinghaus technique.9 The results of this study showed that 60% of deer aged as 2.5-years-old and older were incorrect. They concluded that age could be assigned confidently when using only three categories: fawn, yearling, and adult.

In a study using the cementum annuli technique on mule deer, the estimated error rate for aging was 17%. Matson’s Lab in Milltown, Montana, which conducts cementum annuli analysis, states that this technique is almost 95% reliable for mule deer in the northern regions of the United States and is between 80% to 90% accurate for mule deer in the southwestern United States. Another important finding was that females tended to be incorrectly aged more often than males. However, the reliability for white-tailed deer is much lower, as seen in a study in Florida that had two groups of paired incisors sent to various labs for aging.8 The first group of paired incisors were assigned the same age using cementum annuli in fifteen out of the ninety-nine samples for a matching rate of 15%. The second group had twenty-two out of one hundred samples aged the same for a rate of 20%. Across both samples, the age assigned by the tooth wear and replacement technique matched in only twenty-seven of 209 cases for a rate of 13%.

In general, aging a wild white-tailed deer older than 2.5-years-old is only an approximation of age, and neither technique can accurately assign an age in all situations. However, the Severinghaus technique has the advantage over the cementum annuli technique because fawns, 1.5-years-old deer, and 2.5-years-old and older, can be assigned to these three categories with accuracy. Also, the Severinghaus technique can be used in the field, and collecting a tooth sample to be sent to a laboratory for costly analysis ($75 for four incisors) is not necessary. The remainder of this paper will focus on how to use the Severinghaus technique.

How to Classify Deer by Age Class

White-tailed deer are classified into age classes based on half years, such as 1.5-years-old and 2.5-years-old because typically, a deer is born in May or June but may not be harvested until November or December, making it six months older than its birthdate. Unless a deer was tagged at birth, the only three age classes that can be used to age white-tailed deer with any certainty are fawn, 1.5-years-old (or yearling), and 2.5-years-old and older (mature). While we will discuss how to age a jawbone using categories up to 7.5-years-old, the technique is very subjective, and it may be dependent on a variety of environmental factors that influence the wear of teeth.

Key Terms and Characteristics for Aging a Deer

To age a white-tailed deer using the tooth replacement and wear technique, it is necessary to first understand the parts of a jawbone and the corresponding terminology. This section will define key terms and illustrate the characteristics through a series of photos.

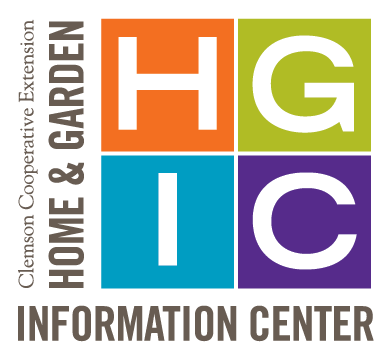

Jaw teeth on a deer can be seen and easily counted, but a tooth may have either two or three cusps (a point or ridge of a tooth, when viewed from the side) that comprise a single tooth (figure 1). The tooth highlighted in figure 1 has two cusps.

Figure 1. Jawbone of a white-tailed deer indicating a single tooth and the cusps for that tooth. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

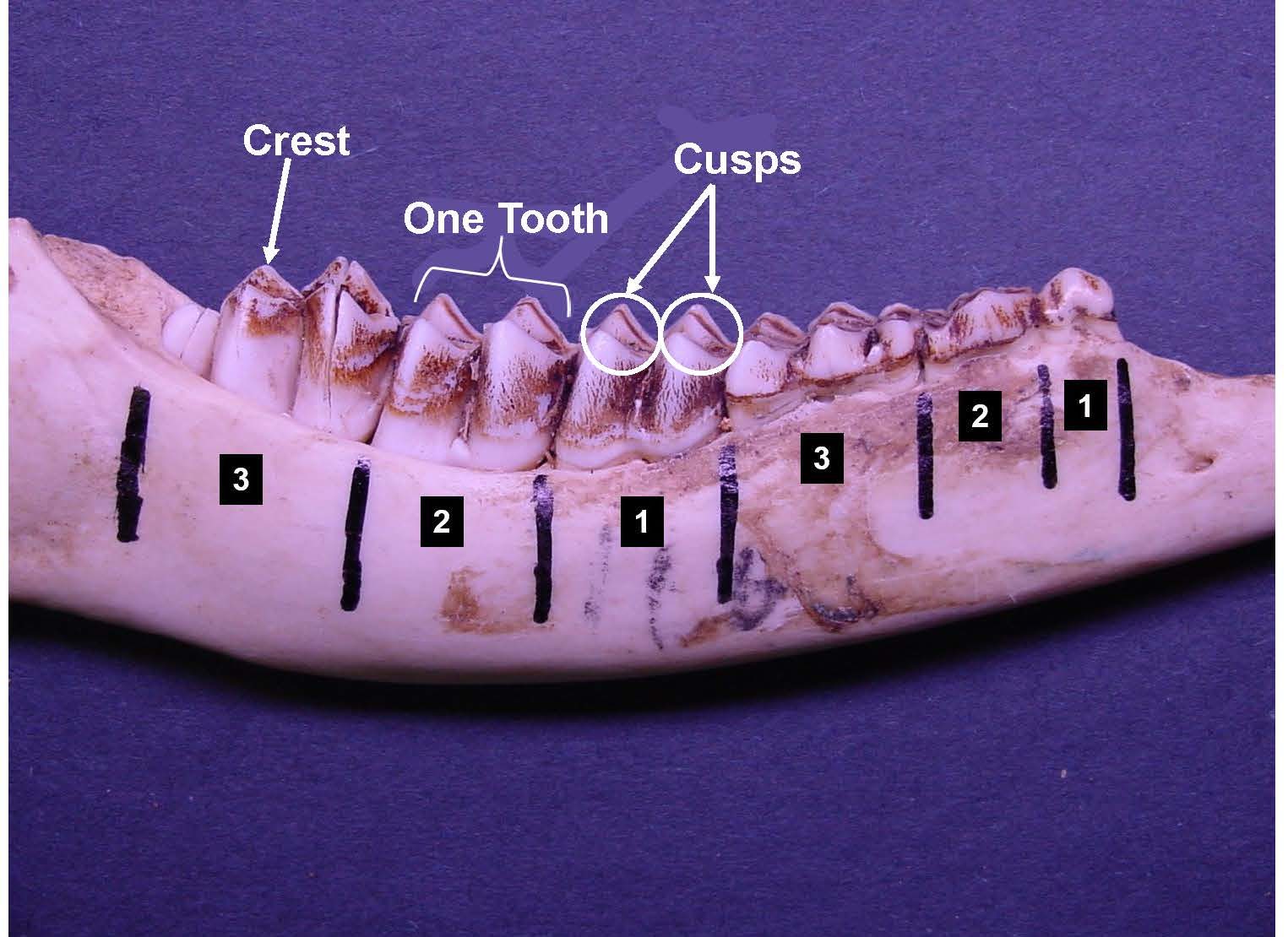

Figure 2 shows the jawbone of a 19-month-old white-tailed deer, which has three molars and three premolars. The molars erupt as permanent teeth, are the teeth in the rear of the jaw, and are typically used for grinding food. The premolars in the front of the jaw are erupted between 3 to 4 months of age and are replaced with permanent teeth, which are used for cutting or tearing food.

Figure 2. Jawbone of a white-tailed deer showing three molars and three premolars. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

Enamel is the white part of the tooth, while dentine is the darker part of the tooth (figure 3).

Figure 3. Jawbone of a white-tailed deer showing dentine and enamel. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

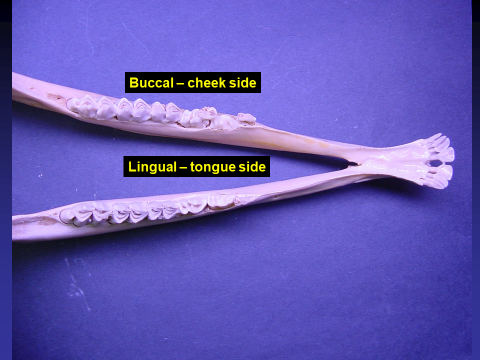

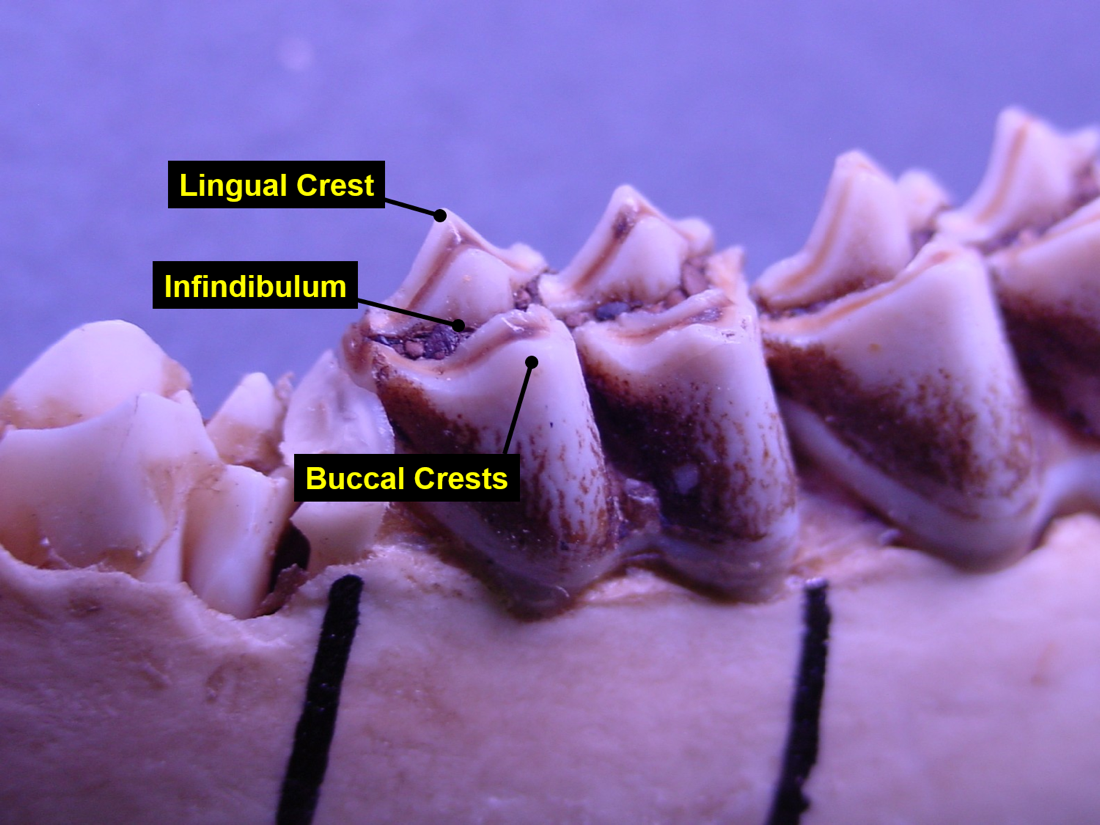

The term buccal refers to the side of the jaw next to the cheek, and lingual refers to the side of the jaw next to the tongue (figure 4). Buccal crests are the ridges on the tooth that are on the cheek side of the jaw, and lingual crests are the crests on the tongue side of the jaw (figure 5). Finally, the infundibulum is the space between the lingual crest and the buccal crest (figure 5). As a deer ages and the teeth wear, the infundibulum becomes more pronounced.

Figure 4. Jawbone of a white-tailed deer showing the buccal and lingual side of the teeth. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

Figure 5. Jawbone of a white-tailed deer showing the infundibulum, lingual, and buccal crests. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

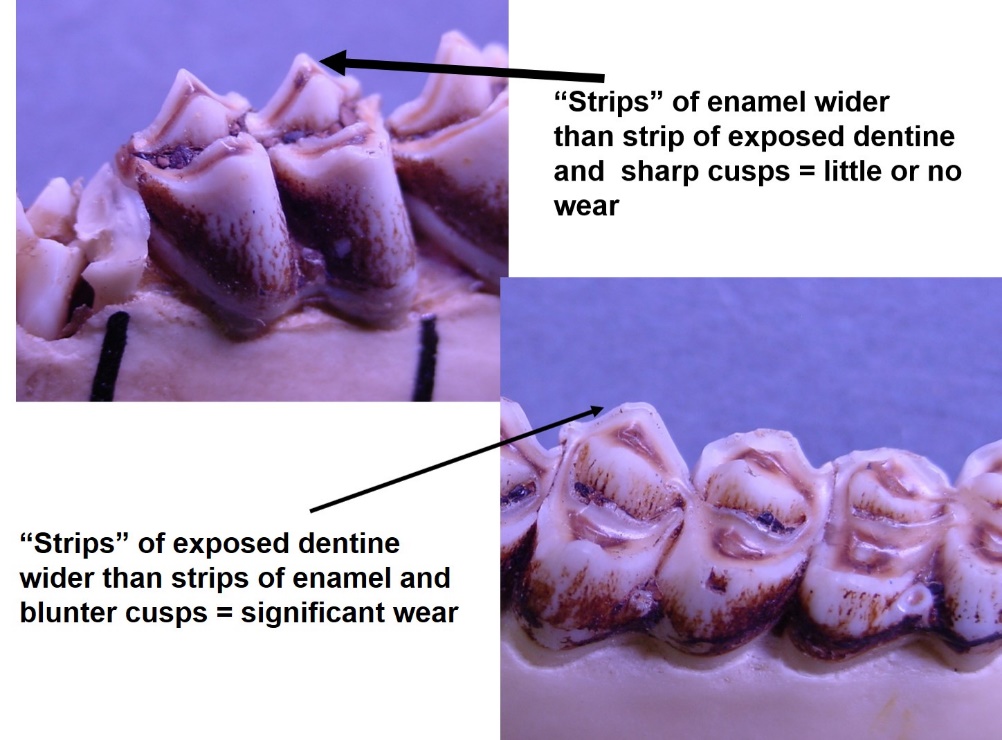

The width of the dentine relative to the width of the enamel and the sharpness or bluntness of the crests are used to determine the wear on a tooth (figure 6). This is an important characteristic when age is determined using tooth wear.

Figure 6. Comparison of enamel versus dentine on teeth of a white-tailed deer. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

How to Use the Aging Keys to Age Deer

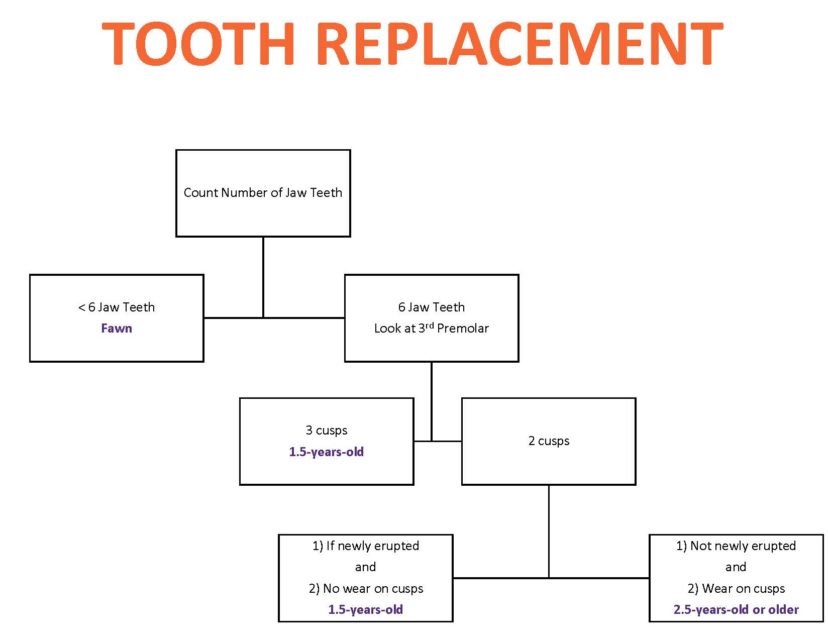

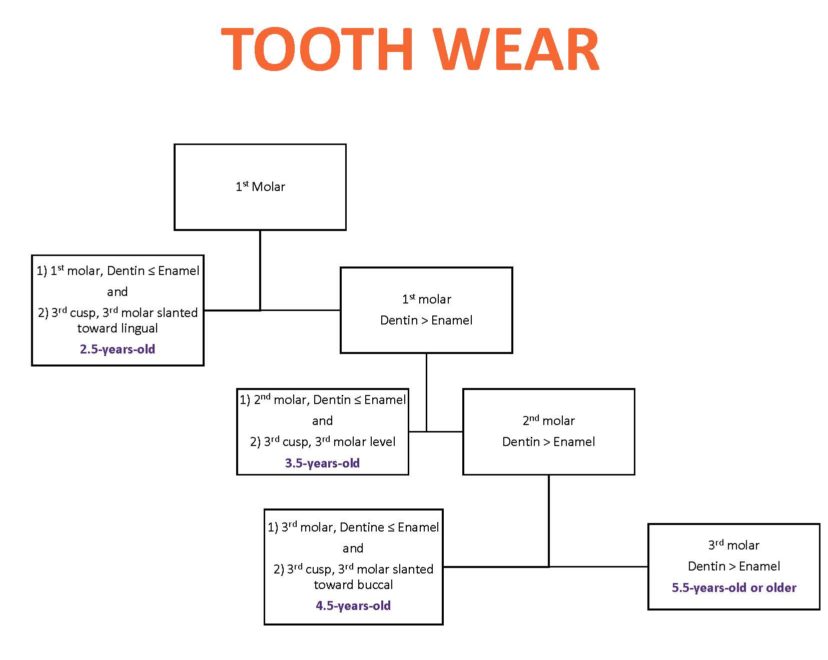

The aging keys (figure 7 and figure 8) illustrate how to age deer using tooth replacement along with tooth wear. Remember, deer will first replace temporary teeth with permanent teeth when they are less than 19-months-old, which means that tooth eruption and replacement is utilized initially (figure 7). For a tooth to be considered “newly erupted,” the tooth is not the same height as the adjacent teeth, and there is no wear on the crests. This technique will age deer to 1.5-years-old and then starts the process for using tooth wear to age deer as 2.5-years-old and older, which is the tooth wear key (figure 8).

To age a deer, start with the Tooth Replacement key (figure 7). Once the age is determined to be 2.5-years-old or older, then follow the Tooth Wear key (figure 8). The key for aging deer only goes to 7.5-years-old and older. As research has shown, there is a great deal of variation in tooth wear among deer, so even assigning an age other than “mature” is subject to lower accuracy, reliability, and confidence.

Figure 7. Key for aging white-tailed deer younger than 2.5-years-old using the tooth replacement technique. Key developed by Susan T. Guynn, Clemson University.

Figure 8. Key for aging white-tailed deer 2.5 years and older using the tooth wear technique. Key developed by Susan T. Guynn, Clemson University.

How to Classify Deer by Age Group

Fawn

Counting teeth is the first step in determining if a deer is a fawn, a yearling, or 2.5-years or older. A mature deer has six jaw teeth, three premolars, and three molars (figure 2). If a deer has less than six jaw teeth, it will be classified as a fawn. The eruption patterns can further indicate the age of a fawn as either between 3- to 4-months-old (figure 9), 4- to-6 months-old (figure 10), and 7- to 9-months-old (figure 11).

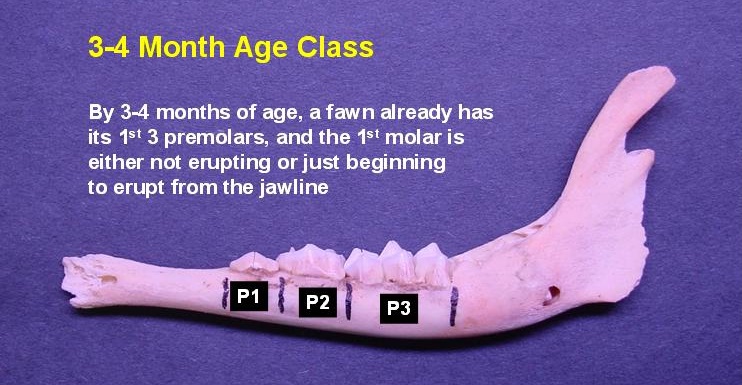

3- to 4-month-old fawn:

- Only first three premolars are present.

- No sign of the first molar, or the first molar is just starting to erupt. In figure 9, the first molar has not started to erupt.

Figure 9. Jawbone of a 3- to 4-month-old white-tailed deer. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

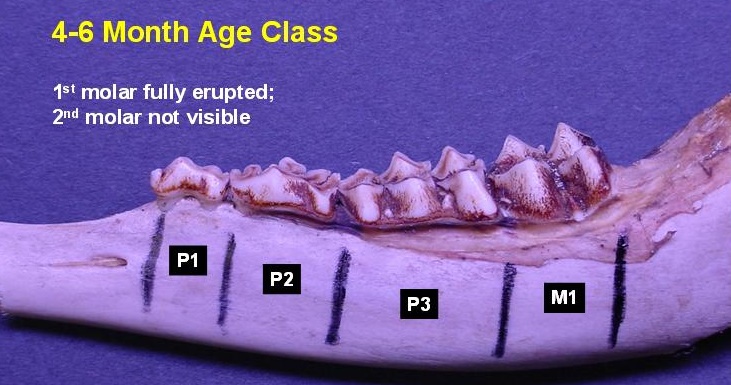

4- to 6-month-old fawn:

- First molar is erupted.

- Second molar has not started to erupt. Notice that the second molar is not visible in figure 10.

Figure 10. Jawbone of a 4- to 6-month-old white-tailed deer. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

7- to 9-month-old-fawn:

- Second molar that is either erupting or fully erupted, as shown in figure 11.

- The third molar is not visible at all, meaning that a 7- to 9-month-old deer has only five teeth at this point.

Figure 11. Jawbone of a 7- to 9-month-old white-tailed deer. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

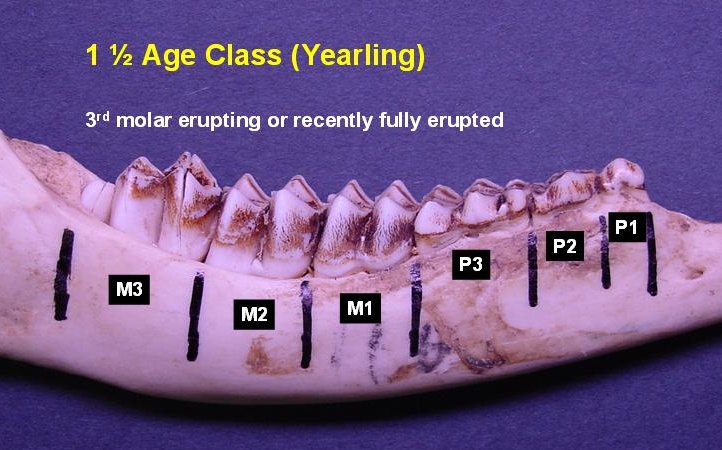

1.5-Year-Old Deer

See figures 12-13 for photos of 1.5-year-old jawbones.

- Has six jaw teeth – three premolars and three molars.

- Third molar will still be erupting or emerging from the jawbone (figure 12)

- Third premolar will have three cusps (figure 13).

Figure 12. Jawbone of a 1.5-year-old white-tailed deer showing the 3rd molar still erupting. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

Figure 13. Jawbone of a 1.5-year-old white-tailed deer showing 3rd premolar and eruption of the molar. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

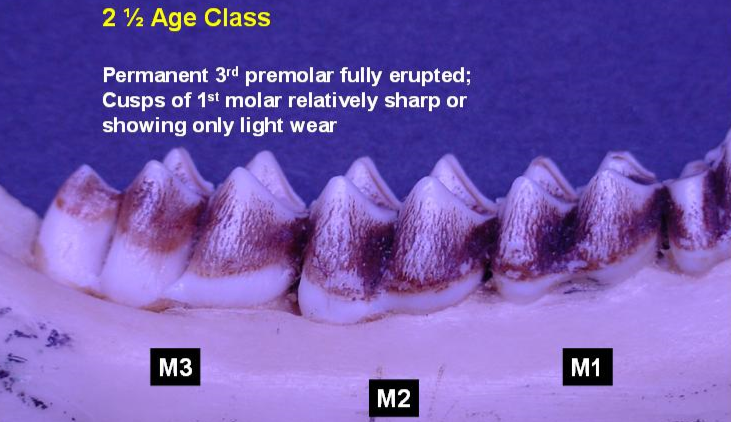

2.5-Year-Old Deer

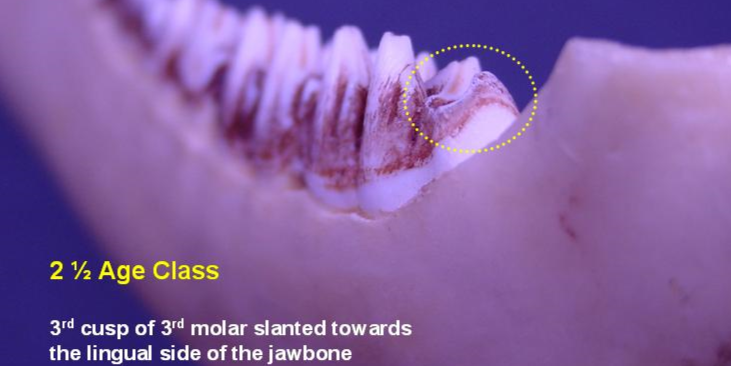

See figures 14-16 for photos of 2.5-year-old jawbones.

- Cusps of the first molar relatively sharp or showing only light wear (figure 14).

- Minimal wear showing on molars; minimal dentine showing on the cusps of the first molar (figure 15).

- Third cusp of third molar slanted towards the lingual side of the jawbone (figure 16).

Figure 14. Jawbone of a 2.5-year-old white-tailed deer showing molars. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

Figure 15. Jawbone of a 2.5-year-old deer showing wear patterns. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

Figure 16. Jawbone of 2.5-year-old white-tailed deer showing slant of 3rd cusp of 3rd molar. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

3.5-Year-Old Deer

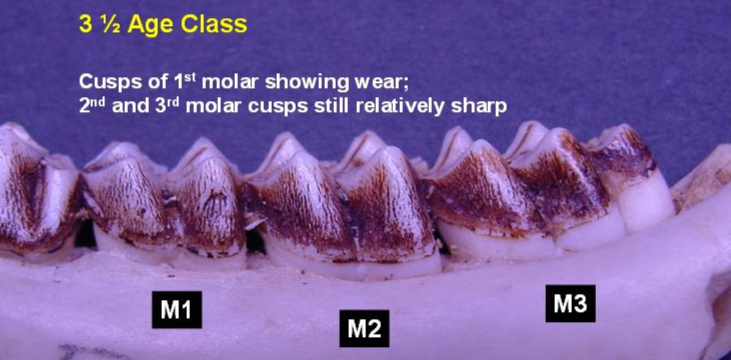

See figures 17-19 for photos of 3.5-year-old jawbones.

- Cusps of the first molar showing significant wear (figure 17).

- Second and third molar cusps still relatively sharp and showing only slight wear (figure 18).

- Third cusp of the third molar relatively level (figure 19).

Figure 17. Jawbone of 3.5-year-old white-tailed deer showing wear pattern from the side. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

Figure 18. Jawbone of 3.5-year-old white-tailed deer showing wear pattern from top. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

Figure 19. Jawbone of 3.5-year-old white-tailed deer showing wear pattern from back. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

4.5-Year-Old Deer

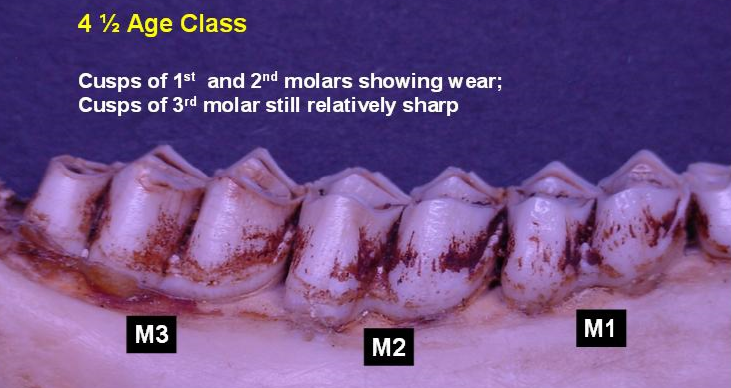

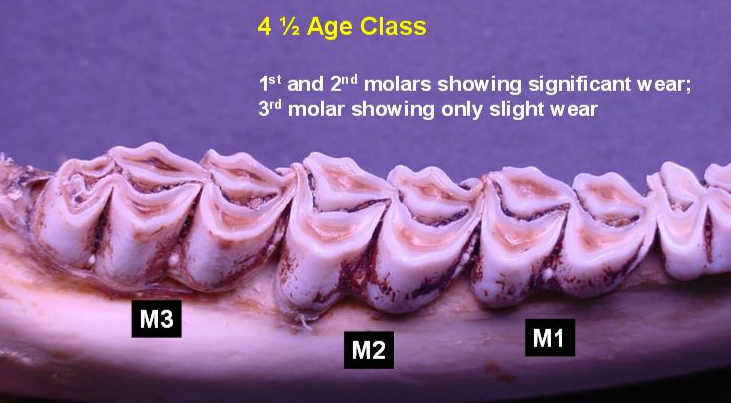

See figures 20-22 for photos of 4.5-year-old jawbones.

- Cusps of the third molar still relatively sharp and only slight wear (figure 20).

- Cusps of first and second molars showing significant wear (figure 21).

- Third cusp of the third molar slanted toward the buccal side of the jawbone (figure 22).

Figure 20. Jawbone of 4.5-year-old white-tailed deer showing wear pattern from the side. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

Figure 21. Jawbone of 4.5-year-old white-tailed deer showing wear pattern from top. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

Figure 22. Jawbone of 4.5-year-old white-tailed deer showing wear pattern from back. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

5.5-Year-Old Deer

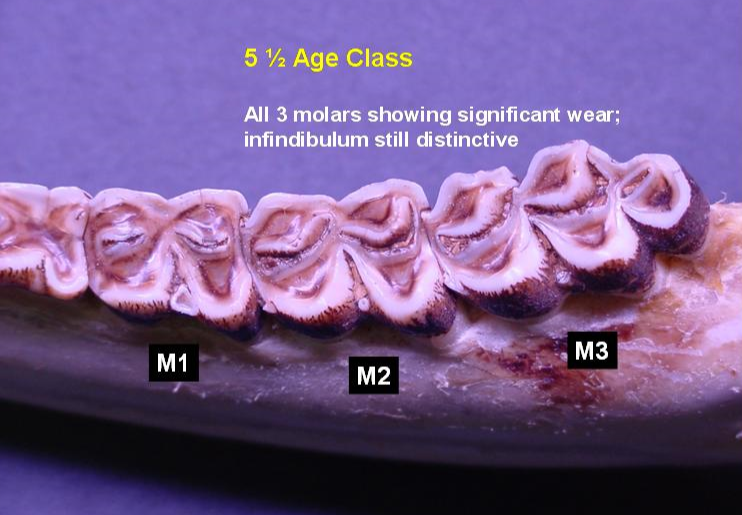

See figures 23-24 for photos of 5.5-year-old jawbones.

- Cusps of all molars showing wear and are without sharp cusps (figure 23).

- All three molars showing significant wear (figure 24).

- Infundibulum still distinctive (figure 24).

Figure 23. Jawbone of 5.5-year-old deer showing wear pattern from the side. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

Figure 24. Jawbone of 5.5-year-old white-tailed deer with all three molars showing significant wear from the top and infundibulum still distinctive. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

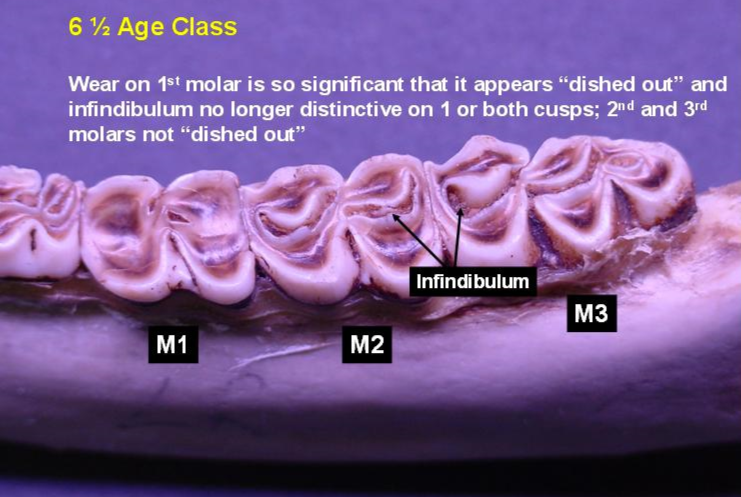

6.5-Year-Old Deer

See figures 25-26 for photos of 6.5-year-old jawbones.

- All three molars are flattened (figure 25).

- Wear on first molar so significant that is appears “dished out” (figure 26).

- Infundibulum no longer distinctive on one or both cusps (figure 26).

- Second and third molars not “dished out” (figure 26).

Figure 25. Jawbone of 6.5-year-old white-tailed deer showing wear pattern from the side. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

Figure 26. Jawbone of 6.5-year-old white-tailed deer showing wear pattern from top. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

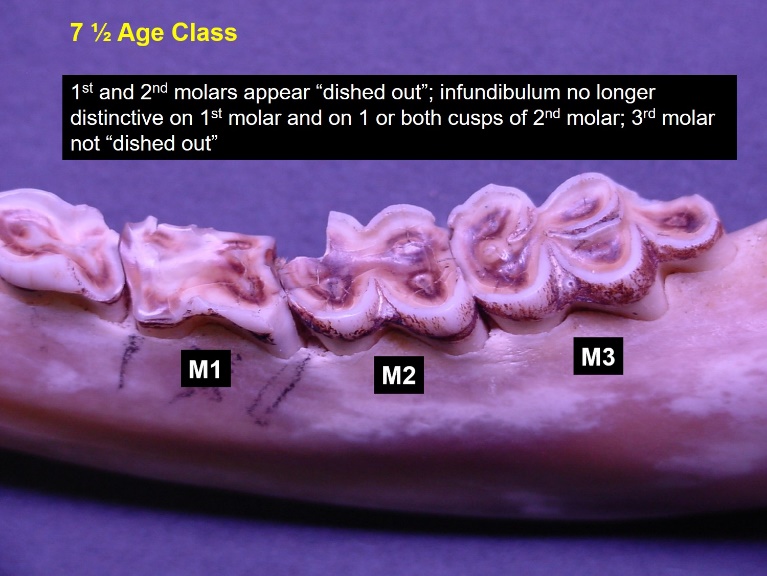

7.5-Year-Old Deer and Older

See figure 27 for a photo of a 7.5-year-old jawbone.

- First and second molars appear “dished out.”

- Infundibulum no longer distinctive on the first molar and on one or both cusps of the second molar.

- Third molar is not “dished out.”

Figure 27. Jawbone of 7.5-year-old white-tailed deer showing wear pattern. Image credit: William F. Moore, Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College.

Conclusions

Aging white-tailed deer is important in order to provide context for interpreting metrics such as body weight, antler development, and reproductive rates. There are two general techniques for aging a deer, Severinghaus and cementum annuli. This paper introduced two keys that biologists and hunters can use to age white-tailed deer in the field using the Severinghaus technique. While neither aging technique is completely accurate, the Severinghaus technique can be utilized in the field and does not require costly laboratory analysis.

Appendix

Buccal – refers to the side of the jaw next to the cheek

Cusp – the points or ridges of a tooth

Crest – top of the cusps

Dentine – darker part of the tooth

Enamel – white part of the tooth

Infundibulum – space between the lingual crest and the buccal crest

Lingual – side of the jaw next to the tongue

Molar – are three permanent teeth in the rear of the jaw

Premolar – are three teeth in the front of the jaw and erupt between 3 to 4 months; are replaced with permanent teeth

Tooth – may have two or three cusps

References Cited

- US Department of the Interior. National survey of fishing, hunting and wildlife-associated recreation. Washington, DC: US Department of the Interior; 2011 [accessed 2019 Nov 11]. https://www.census.gov/prod/2012pubs/fhw11-nat.pdf.

- Severinghaus CW. Tooth development and wear as criteria of age in white-tailed deer. Journal of Wildlife Management. 1949;13(2):195–216.

- Severinghaus CW, Cheatum EL. The deer of North America. WP Taylor, editor. Harrisburg (PA): Stackpole and The Wildlife Institute. 1956. Life and times of the white-tailed deer, Chapter; p. 57–186.

- Gilbert FF. Aging white-tailed deer by annuli in the cementum of the first incisor. Journal of Wildlife Management. 1966;30(1):200–202.

- Lockard GR. Further studies of dental annuli for aging white-tailed deer. Journal of Wildlife Management. 1972;36(1):46–55.

- Cook RL, Hart RV. Ages assigned known-age Texas white-tailed deer: tooth wear versus cementum analysis. 33rd Proceedings of Annual Conference SE Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies; 1979 Oct 24–27; Hot Springs (AK), p. 195–201.

- Hackett, EJ, Guynn, Jr, DC, Jacobson, HA. Differences in age structure of white-tailed deer in Mississippi produced by two aging-techniques. 33rd Proceedings of Annual Conference SE Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies; 1979 Oct 24-27; Hot Springs (AK), p. 25–29.

- Woodard DA, Field J. Consistency and reliability of deer ages from Central Florida. 40th Annual Meeting of the Southeast Deer Study Group; 2017 Feb 27–Mar 1; St. Louis, MO.

- Gee KL, Holman JH, Causey MK, Rossi AN, Armstrong JB. Aging white-tailed deer by tooth replacement and wear: a critical evaluation of a time-honored technique. Wildlife Society Bulletin. 2002;30(2):387–393.