Buying local beef can be a challenge for local businesses and consumers alike. Because farmers are familiar with their product, they may not realize how much information new customers need to make a purchasing decision. This publication aims to help first-time buyers (and sellers) communicate better to increase local beef sales.

Buying Local Beef

Buying local beef is a great way to support local producers. For those that are new to the local purchasing experience, there are six factors you should consider: (1) finding reputable producers, (2) familiarizing yourself with animal traits, (3) understanding inspection, labeling, and grading, (4) choosing processing options, (5) calculating price per pound, and (6) making storage arrangements.

Finding Reputable Producers

It goes without saying that you should have an element of trust in the producer before buying from them. You may learn a lot from a website and social media or post a question on Facebook to find out where friends and coworkers buy local beef. A farmers market is a great venue, too, as you will get to meet and talk to the producer. Online product reviews can also be helpful if the producer has a web presence.

Some websites list local producers in South Carolina, including

- Certified South Carolina Grown, www.certifiedsc.com

- South Carolina Department of Agriculture

- WLTX-TV News 19 list of local meat producers (May 2020)

In addition to reviewing available information about a producer, it is a good idea to ask a producer about their operations and products. Some questions you may want to consider asking are listed below.

- How long have they been in business supplying beef?

- What do their animals’ diets comprise of throughout the year?

- Do they purchase calves and or rear their own? If purchased, where do they come from, and how are they managed?

- Are their animals given health products, and if so, what?

- Do they provide product samples?

- Who else do they sell beef to regularly?

- How do their contracts work?

- How does their pricing change?

- Do they deliver?

- Is beef bought processed or as an animal? If processed, which processor(s) do they use?

- Has the beef received any recognition?

- How much beef can they supply at any given time?

- What is the minimum order size?

It is important to note that it is not uncommon for producers to request a deposit well in advance of product delivery. Make sure you clearly communicate expectations regarding price, timeline, and delivery.

Familiarize Yourself with Animal Traits

How the Animal Was Raised

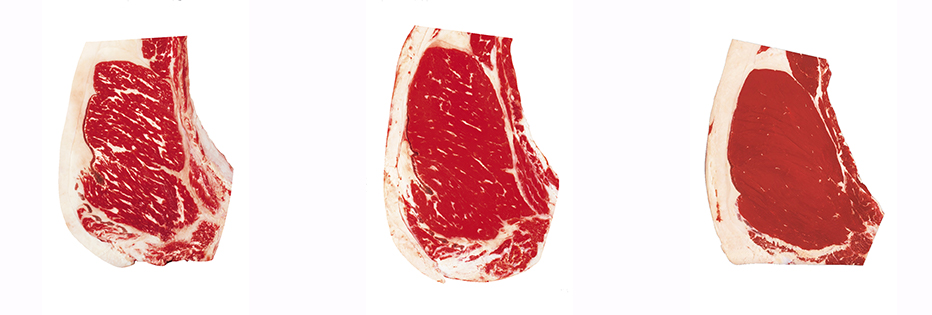

Beef animals spend most of their lives eating forage, either pastured forage (grass) or stored forage (typically dry hay). Steers and heifers destined for slaughter are “finished,” meaning they spend a period of time in a feedlot eating grain to increase marbling (intramuscular fat, figure 1) and change their fat color from yellow to white. Yellow fat is a result of eating grass forage. Finishing animals on high energy grass takes approximately one hundred days. If you are buying an animal that is “pasture-finished” or “grass-finished,” it means that the animal spends a portion of its time on higher quality forage to accomplish fattening, but the fat will retain a yellow color. You should also expect less marbling from grass-finished beef, which may result in a less tender and juicy cut of meat.

Figure 1: Marbling (intramuscular fat) differences in beef ribeye steaks. Image credit: US Department of Agriculture (USDA).

The Sex and Age of the Animal

There are a number of different sex classifications for beef animals (table 1). Typically, the best beef products come from younger heifers and steers, which are usually sold for retail cuts and restaurant menus.

Table 2 shows how the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) uses a maturity classification to assign ages to beef animals. While older animals (maturity C through E) will yield the same retail cuts as a younger animal, the meat may be tougher and not taste as good. Aged cows and bulls are usually processed into ground meat or in a manner that increases tenderness and taste (e.g., lunchmeat, sausage, jerky).

Table 1. Sex classification chart for beef animals.

| Young Animal (either sex) | Calf |

| Young Female | Heifer Calf |

| Young Male | Bull Calf |

| Young Castrated Male | Steer Calf |

| Immature Female | Heifer |

| Immature Male | Bull |

| Immature Castrate | Steer |

| Mature Female | Cow |

| Mature Male | Bull |

| Mature Castrate (Castrated after maturity) | Stag |

Source: Encyclopedia Britannica.2

Table 2. Beef maturity classifications.3

| A | 9–30 Months |

| B | 30–42 Months |

| C | 42–60 Months |

| D | 60–96 Months |

| E | Greater than 96 Months |

Understand Inspection, Labeling, and Grading

Meat Inspection and Labeling

It is important to understand that there is a difference between buying retail cuts of meat and buying an animal. If you are buying an animal (with terms like whole, half, or quarter), you or the producer must arrange to have it processed at a local facility. While the product is still expected to be safe and wholesome, many local facilities are not routinely inspected. In this case, the meat products will be labeled “Not for Sale.”

If you are buying labeled retail cuts of meat, the animal must have been processed at a federal or state inspected facility. Federal and state inspectors are tasked with an antemortem (before harvest) inspection of the animal, humane harvesting, and inspection of specific organs. The inspection systems ensure a safe and healthy meat supply. The labels on these meat products will have a stamp certifying the meat was inspected and identifying which facility processed it.

Meat Grading

Meat grading is a voluntary USDA (federal inspection) provided service. Beef can be graded into eight different categories (from highest to lowest): Prime, Choice, Select, Standard, Commercial, Utility, Cutter, and Canner.1 Grading is based on both animal age and the amount of marbling in the meat. In general, the more marbling (figure 1), the better the flavor and moisture of the additional fat within the muscle. Certain beef products are marketed by quality grade. For instance, to be classified as Certified Angus Beef, an animal must grade either choice or prime. Currently, no South Carolina processing facilities provide grading services. The www.beefresearch.org website has more information on beef grading.

Choosing Processing Options

Step 1: Slaughter

Slaughter involves the humane killing and dressing of the animal. Traditional slaughter involves restraining and stunning the animal, while Kosher and Halal slaughter may not.4 Dressing refers to the removal of the internal organs, skin, hooves, and head. Often, a dressing percentage is identified, meaning how much of the live animal becomes the carcass, and this value is typically 62%–64%. The animal is then split in half and washed, and a product such as lactic acid or steam is applied to enhance food safety. At this point, the animal is referred to as a carcass, and the processor records the “hanging weight.”

Step 2: Aging

The carcass is then aged in a cooler with a target temperature of 34°F. The aging process tenderizes the meat by allowing protein degradation. The amount of aging time depends on the processor and the desires of the customer. Aging is an expensive process, as cooler space is often limited. The American Meat Science Association provides more information about aging beef on their website.

Step 3: Cutting

After aging, the carcass is broken down into retail cuts. It is important to remember that certain cuts are tradeoffs with other cuts. As an example, you can either request strip steaks and tenderloin or t-bones and porterhouse steaks, but not both. Often the choice is between steaks, roasts, and ground beef. Ground beef is usually produced from lean trimmings with fat added back to get a consistent percent lean/percent fat. Most ground beef found in retail stores is 80% lean and 20% fat. The Clemson Extension Agribusiness Program Team website provides more information about retail beef cuts.

Step 4: Packaging and Further Processing

The product is then either wrapped in freezer paper or vacuum packaged. Not all processors have vacuum packaging as the equipment is expensive. Vacuum packaging also increases the cost of processing. Further processed products such as cubing, sausage, jerky, and snack sticks are options if the processor has the equipment to produce these products. It is worth your time to fully explore what you will be receiving and what capabilities and limitations may exist with the processor.

Calculating Price per Pound

Price per pound is a combination of how much everything costs (raising the animal, processing, packaging, trucking, delivery, and any value-added products) and the total yield (weight of packaged meat products).

Local Beef Costs

You should have realistic expectations about how much beef you are buying and how much it will cost. Local beef is comparably priced to the product you see in a supermarket. You should be receiving a premium product and developing a relationship with your food source. Animals raised in alternative ways (e.g., grass-fed, organic) can have significantly higher production costs. Also, small packing plants have more overhead and expenses (on a per animal basis) than large, high-volume plants; therefore, processing costs will be higher.

Total Yield

For those buying whole, half, or quarter animals, it can be a surprise that a 1,300-pound live beef animal yields under 550 pounds of packaged meat. There are terms and typical beef yields that may help you understand what you are getting for your money (table 3).

- Live weight: what the animal weighed before being sent to the processor

- Dressed or carcass weight: weight after slaughter and before cutting

- Packaged weight: pounds of packaged meat (including bone-in cuts) after cutting

- Boneless meat: how much boneless meat (if requested)

Table 3. Typical processing losses and what to expect in terms of pounds of meat per animal.4

| Animal Species | Live Weight | Dressing % | Carcass Weight | Cut Out

% |

Packaged Meat |

Bone Out % | Boneless Meat |

| Beef | 1312 | 62% | 813 | 68% | 553 | 85% | 470 |

*Note: Depending on preferences for bone-in cuts versus boneless, the amount of organ meats desired, the butcher’s skill, and the amount of fat preferred can cause these yields to vary.

Making Storage Arrangements

Buying a whole or a half carcass will generate a lot of product and require a large amount of freezer space. A good general rule is that a quarter beef animal will take four to five cubic feet of freezer space. Make sure you have the freezer space to store the beef before accepting delivery. Also, monitor your freezer regularly, as a power outage or freezer failure is a very costly event. Generators and freezer temperature alarm systems are cost-effective safety measures for those looking to store a large amount of beef.

Parting Thoughts

If you are buying a whole or partial animal, realize you may have to be creative with some of the less desirable cuts. Beef shanks, oxtails, briskets, tongues, and hearts are some of the items you may receive from the processor. The Clemson Agribusiness Program Team website provides information on cooking methods for these products.

Local beef demand is increasing. As a result, local processors are reporting full schedules for six to eight months out, and those with advanced processing capabilities are booked even further out. Do your research and be patient, as it may take some time to locate an appropriate producer, secure a processing time, and end up with the product in hand.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Kevin Gould of Michigan State Cooperative Extension for his assistance in reviewing this publication.

References Cited

- USDA Agricultural Marketing Service. Beef grades and standards. Washington (DC): US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service; [accessed 2020 Aug 13]. https://www.ams.usda.gov/grades-standards/beef/shields-and-marbling-pictures.

- Britannica. Cattle. Chicago (IL): Encyclopedia Britannica; [accessed 2020 Aug 13] 2021. https://www.britannica.com/animal/Santa-Gertrudis

- Tatum D. Beef grading. Centennial (CO): National Cattlemen’s Beef Association; 2021. BEEF FACTS: product enhancement. https://www.beefresearch.org/resources/product-quality/fact-sheets/beef-grading.

- Texas A&M AgriLife Extension. Kosher and halal. College Station (TX): Texas A&M University, Meat Science Department; [accessed 2020 Aug 13]. https://meat.tamu.edu/ansc-307-honors/kosher-halal/.

- Raines CR. The butcher kept your meat? State College (PA): The Pennsylvania State University, Department of Dairy and Animal Science; [accessed 2020 Aug 13]. https://animalscience.psu.edu/outreach/programs/meat/pdf/the-butcher-stole-my-meat.pdf.

Additional Resources

Fischer M, Richards S, Bolt B. Direct marketing of beef, pork, or lamb: is this an opportunity for you? Clemson (SC): Clemson Cooperative Extension, Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension; 2020. LGP 1058.

Clemson Extension Agribusiness Program Team

Michigan State University Extension, Meat Marketing, and Processing