The Logging Business Survey

Logging business surveys are conducted by researchers and trade associations across the nation. Recent logging business surveys have been conducted in Maine,1,6 Virginia,2 and Minnesota,3 among other states, and a review of logging business surveys and industry trends across the US has also been done.4 A survey of logging businesses provides decision-makers and the public with an understanding of the state of the industry and highlights individual challenges within the logging industry. The University of Georgia has conducted logging business surveys every five years since 1987. To collect information across a larger region, South Carolina loggers have participated in the survey since 2012. Surveys conducted by researchers often get published in peer-reviewed journals with a wealth of detail. This article summarizes the results from the 2017 logging business survey conducted in Georgia and South Carolina5 but will focus on South Carolina results only. The goal of this publication is to provide landowners, foresters, loggers, and policy decision-makers with a condensed version of the most important results of the 2017 South Carolina logging business survey.

Survey Responses

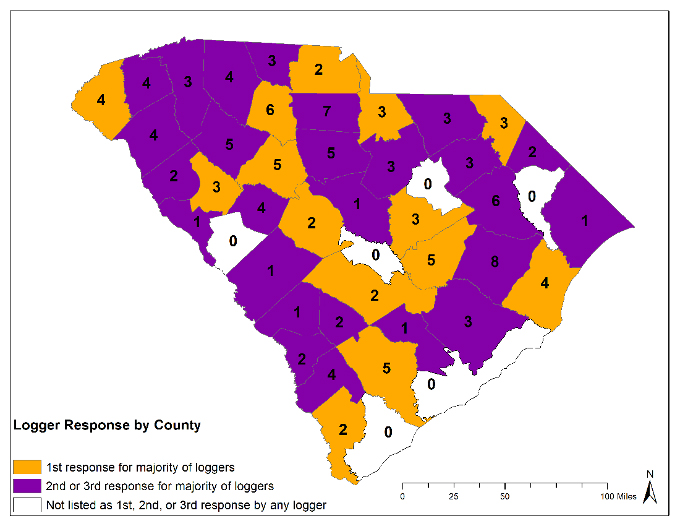

A mail survey was sent to 268 logging businesses in South Carolina in March and April of 2017. Mailing information for logging businesses was provided by the Timber Operations Professional (TOP) logger training program in the state. Fifty-seven surveys were returned; however, only fifty-one were from active logging businesses. Thus, the adjusted response rate of completed surveys was 19.5%. Logging business owners were asked to list the three counties they work in the most, in descending order. Responses indicated that loggers were active in all but six counties (figure 1). Logging occurs in these six counties; however, none of the responding loggers indicated the particular importance of these counties to their business.

Figure 1. Number of times a logger reported a county as one of the three counties they worked in the most. Orange colored counties indicate that this county was ranked first by the majority of the listed loggers. Purple colored counties indicate that this county was ranked second or third by the majority of the listed loggers. White-colored counties were not ranked as one of the three counties most often worked in. Image credit: Patrick Hiesl, Clemson University.

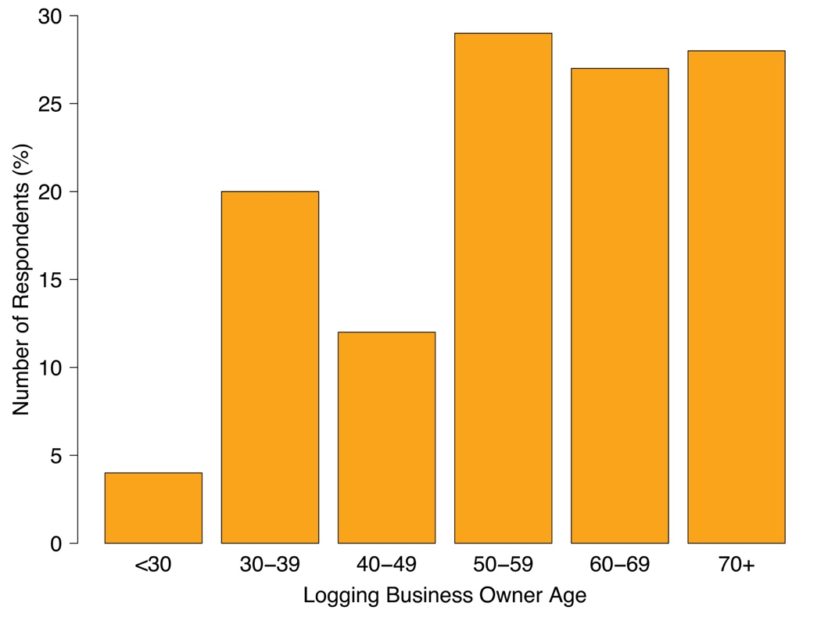

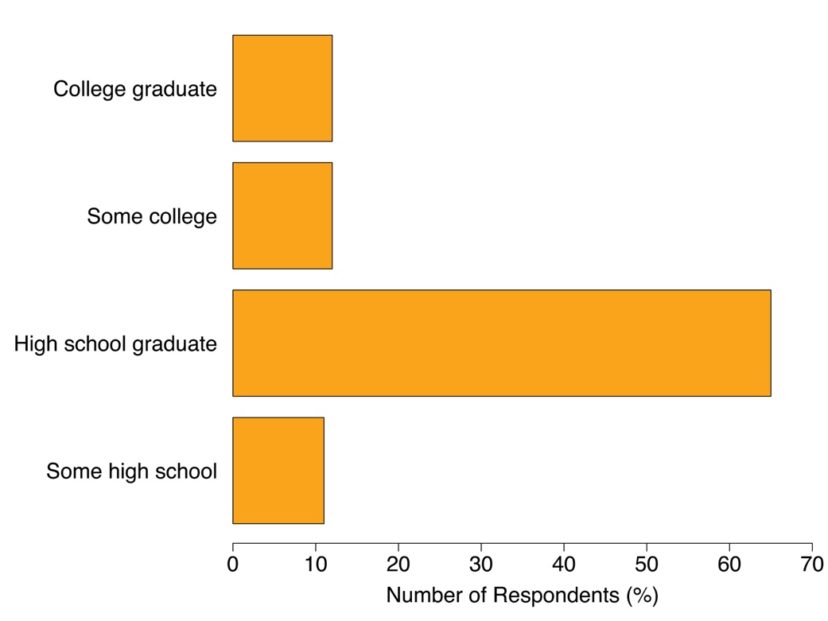

Similar to many states in the US, logging business owners in South Carolina are aging, with almost two-thirds (64%) of the respondents being over the age of fifty (figure 2). The fact that only 24% of the respondents were younger than forty, and only 4% were less than thirty years of age is concerning. Very few young people are entering the trade. As for education, the majority (64%) of logging business owners have a high school degree, with 12% of respondents reporting to have a college/university degree (Associates degree or higher, figure 3). An additional 12% reported that they have attended college or have taken college-level classes but did not graduate with a degree. A college degree is not a necessity for starting a logging business, so it is not surprising to see that the majority of logging business owners have a high school degree.

Figure 2. Logging business owner age distribution as reported in the 2017 logging business survey in South Carolina. Image credit: Patrick Hiesl, Clemson University.

Figure 3. Reported education level of South Carolina logging business owners in 2017. The term “some” indicates that some courses (high school or college) were taken, but no degree was received. A “graduate” received a degree either from high school (high school diploma) or a college/university (Associates or higher). Image credit: Patrick Hiesl, Clemson University.

The average logging business in South Carolina has ten employees. Of these, three are truck drivers. The average logging business consists of one timber harvesting crew. This means that the average logging business is working on one timber harvest at a time and does not have enough equipment to work on multiple timber harvests simultaneously. Furthermore, 78% of respondents indicated that they employ their relatives in the business.

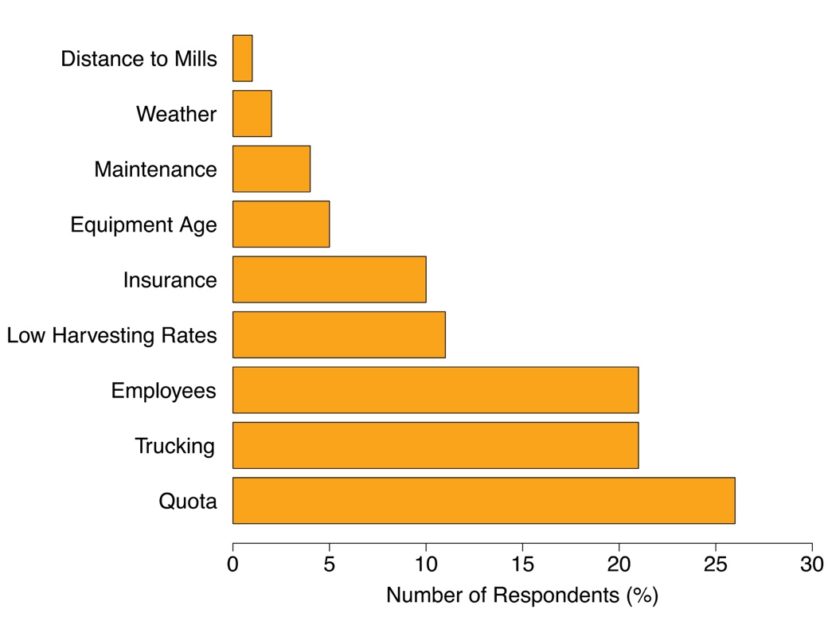

Challenges for a logging business are aplenty. The most-reported challenge of the logging industry was quota (figure 4), the limit set by receiving forest products mills on how many loads of timber they will accept from a given logging company. These limits can change daily and require the logging business owner to find alternative timber markets or to delay the harvest of certain products until a market opens up again. Other challenges include trucking, which is mostly a factor of finding licensed and skilled drivers, or sub-contractors, as well as increased insurance rates. This is not a unique challenge to South Carolina but also impacts other states with a large forest products industry (e.g., Georgia5 and Maine6). Finding skilled equipment operators and dealing with low harvesting rates paid by wood dealers and mills for a logger’s services are also factors that create challenges for logging businesses to stay operational. Some lesser challenging factors in a logging business are equipment and workers’ compensation insurance costs, equipment age and maintenance, weather, and the distance to the mills (figure 4).

Figure 4. Challenges to logging business operations as reported by respondents to the 2017 South Carolina logging business survey. Image credit: Patrick Hiesl, Clemson University.

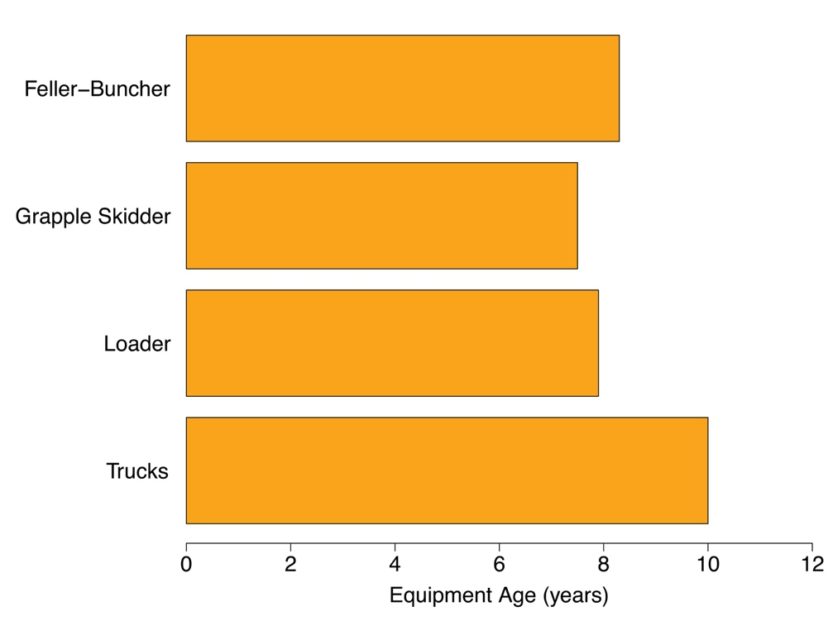

In figure 4, trucking includes responses that reported a shortage of qualified drivers but also included responses indicating challenges with finding or keeping trucking insurance. While not all respondents reported trucking as a particular challenge to their business, almost all logging businesses (96%) reported that they experienced an increase in trucking insurance between 2012 and 2017. The average reported increase in trucking insurance was approximately 31%. Only 4% of logging businesses reported a decrease in trucking insurance; however, no information is available about the reason for this decrease. A lesser challenge is equipment insurance costs. However, 82% of logging businesses reported an increase in equipment insurance costs between 2012 and 2017, with an average increase of approximately 11%. Nine percent of the logging businesses reported a decrease in equipment insurance costs, and another 9% reported that their insurance cost stayed the same. Again, no information for insurance premium discrepancies among loggers was collected. Equipment age for the harvesting equipment averaged approximately eight years (figure 5). Feller-bunchers were reported, on average, to be the oldest in-woods equipment. Of concern was the response for the age of trucks. With a reported average age of approximately ten years, these vehicles may be close to their useful life, given the harsh conditions in which a log truck operates. No information about the actual operating hours on each machine was collected, so it is unknown whether the older equipment was used excessively.

Figure 5. Reported age of common harvesting equipment in South Carolina in 2017. Image credit: Patrick Hiesl, Clemson University.

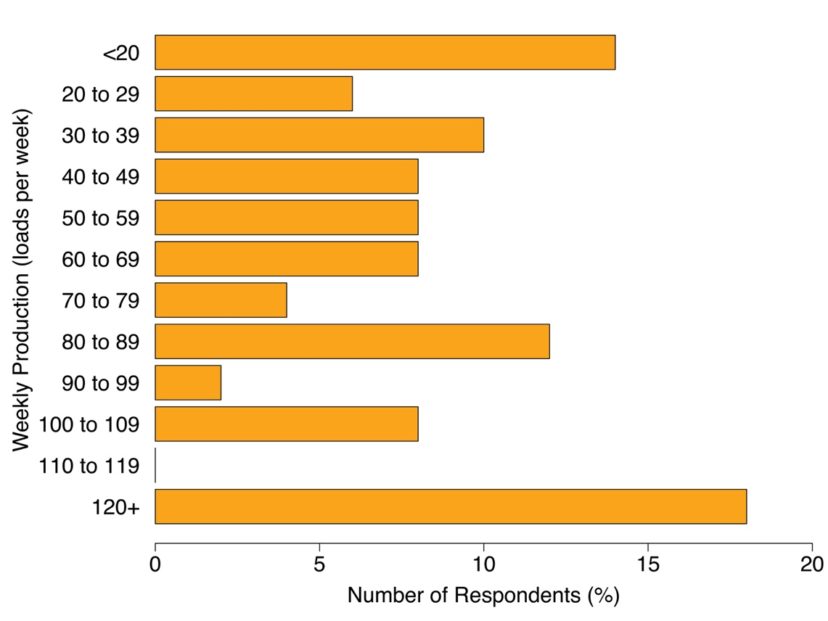

The weekly production of a logging crew is a common measure to assess the size and productivity of a logging business. Respondents were asked to report the average weekly production of their logging business in tons. Since many landowners, foresters, and loggers, are more familiar with the measure of loads per week, the reported tonnage has been converted to loads per week. The conversion factor used for this publication was twenty-five tons per truckload. Reported weekly production ranged from less than twenty loads per week to over 120 loads per week (figure 6). Approximately 40% of the logging businesses that reported weekly production produced between forty and ninety loads per week. The average weekly production differed between the logging businesses in the Piedmont and the Coastal Plain, with an average of sixty loads per week for Piedmont loggers and an average of ninety loads per week for Coastal Plain loggers. As the average South Carolina logging business consists of one logging crew, the weekly logging crew production may be similar to the reported weekly production of the logging business. Logging businesses that reported over one hundred loads per week were mostly situated in the Coastal Plains region of the state, but also had two or more individual logging crews in their business.

Figure 6. Average weekly production for logging businesses that responded to the 2017 South Carolina logging business survey. One truckload was estimated to be twenty-five tons. Logging businesses reporting over one hundred loads per week typically consisted of two or more logging crews and were mostly situated in the Coastal Plains region. Image credit: Patrick Hiesl, Clemson University.

Summary

Logging businesses are an integral part of forest management. Often it is hard to understand why a logging business cannot do what we expect them to do for the price we want. Understanding the structure of a logging business and the challenges they are faced with are crucial for a fruitful relationship between loggers, foresters, and landowners. This summary provides a snapshot of the logging businesses in South Carolina and highlights the challenges of an aging workforce and aging equipment. It also highlights some of the challenges that logging businesses have been experiencing in the past, from quotas to significant increases in insurance costs. The variation of logging businesses in the state of South Carolina from small low production businesses with less than twenty loads per week to high production businesses with over 120 loads per week shows that we are well equipped to handle many different harvest tract sizes. As these logging businesses are not evenly distributed across the state, it may be difficult to find a small-sized logging business to cut a five-acre tract; however, with some effort and communication, a forester or landowner may be able to find an adequately sized logging crew in their region. A full report on the results and methods used in this survey are available.5

References Cited

- Bailey MR, Crandall MS, Kizha AR, Green Sundefined. The economic contribution of logging and trucking in maine. Economic Development. 2020 Mar 4. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mcspc_ecodev_articles/16/.

- Barrett SM, Bolding MC, Munsell JF. Characteristics of logging businesses across Virginia’s diverse physiographic regions. Forests. 2017;8(468):13. doi:10.3390/f8120468.

- Blinn CR, O’Hara TJ, Chura DT, Russell MB. Minnesota’s logging businesses: an assessment of the health and viability of the sector. Forest Science. 2015;61(2):381–387. doi:10.5849/forsci.14-013.

- Conrad JL, Greene WD, Hiesl P. A review of changes in US logging businesses 1980s–present. Journal of Forestry. 2018;116(3):291–303. doi:10.1093/jofore/fvx014.

- Conrad JL, Greene WD, Hiesl P. The evolution of logging businesses in Georgia 1987–2017 and South Carolina 2012–2017. Forest Science. 2018;64(6):671–681. https://academic.oup.com/forestscience/article/64/6/671/5043191.

- Koirala A, Kizha AR, Roth BE. Perceiving major problems in forest products transportation by trucks and trailers: a cross-sectional survey. European Journal of Forest Engineering. 2017;3(1):23–34