The prevalence of rotavirus, coronavirus, E. coli K99, and Cryptosporidium parvum were determined in fecal samples from 2012 to 2016 in young beef and dairy calves from South Carolina farms. Samples originated from calves presented for necropsy and from submitted fecal samples and were analyzed for these four pathogens using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). One hundred and forty-two fecal samples were tested, and eighty-seven were positive for at least one pathogen. Positivity rates for each pathogen were rotavirus 47%, coronavirus 11%, E. coli K99 7%, and Cryptosporidium parvum 24%. Additionally, 23% of the fecal samples were positive for more than one of these pathogens. On a farm basis, 45% of farms were rotavirus positive, 18% were coronavirus positive, 9% were E. coli K99 positive, 28% were Cryptosporidium parvum positive, and 26% were positive for more than one pathogen.

Introduction

Neonatal calf diarrhea (scours) causes illness, death, and production loss (poor weight gain) in both beef and dairy cattle herds.1 Four major causes of neonatal bovine diarrhea are rotavirus, coronavirus, Cryptosporidium spp., and E. coli (K99).2,3,4 All four of these microorganisms are present in North America; however, the prevalence of each in South Carolina calves is not known. Clinical signs and age-of-onset are similar for these four pathogens, and disease is more severe when more than one of these agents is present simultaneously in a calf. Thus, testing for all four organisms allows the development of more clinically relevant information for owners. Because these diseases have a significant economic impact on cattle production, obtaining occurrence data for these will give South Carolina beef and dairy producers actionable information they can use to reduce, eliminate, or control the economic impact of calf diarrhea on their operations.

Materials and Methods

The Fassisi BoDia® lateral flow ELISA antigen assay (Fassisi, Goettingen, Germany), which detects rotavirus, coronavirus, E. coli K99, and Cryptosporidium parvum in feces was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One fecal sample was collected from each calf two months of age or younger submitted to the Clemson Veterinary Diagnostic Center (CVDC) for a necropsy by a South Carolina owner between January 2012 and December 2016 (N=80). Additional calf fecal samples were also collected from South Carolina calf owners (N=62) and were similarly examined. In total, 142 individual fecal samples from sixty-seven individual premises were examined.

Results

Sixty-one percent (86/142) of fecal samples were positive for at least one pathogen, and 25% (35/142) of fecal samples were positive for more than one pathogen. Positive fecal samples came from both dairy (62%) and beef (38%) calves. The number and percentage of samples positive for each pathogen are shown in table 1 for all calves, beef calves only, and dairy calves only.

Table 1. Pathogens from diarrheic calves in South Carolina. Number of positive fecal samples / total number of fecal samples (percentage of total fecal samples).

| Pathogen | All Calves

(N=142) |

Beef Calves

(N=55) |

Dairy Calves

(N=87) |

| No pathogens | 55/142

(39%) |

28/55

(51%) |

28/87

(32%) |

| Rotavirus | 67/142

(47%) |

19/55

(35%) |

47/87

(54%) |

| Coronavirus | 15/142

(11%) |

7/55

(13%) |

8/87

(9%) |

| E. coli K99 | 10/142

(7%) |

0 | 10/87

(11%) |

| C. parvum | 34/142

(24%) |

7/55

(13%) |

27/87

(31%) |

Note: For each pathogen, the dairy:beef ratio was rotavirus 72%:28%, coronavirus 54%:46%, and C. parvum 69:31%. E. coli K99 was found in only dairy calves.

In the thirty-five fecal samples with more than one pathogen, the number and percentage positive for each combination of pathogens are shown in table 2 for all calves, beef calves only, and dairy calves only.

Table 2. Pathogen combinations from diarrheic calves in South Carolina 2012-2016. Number of positive fecal samples / total number of fecal samples (percentage of total fecal samples).

| Pathogen Combination* | All Calves

(N=142) |

Beef Calves

(N=55) |

Dairy Calves

(N=87) |

| No pathogens | 56/142

(39%) |

28/55

(51%) |

28/87

(32%) |

| Only one pathogen | 55/142

(39%) |

23/55

(42%) |

32/87

(37%) |

| Rotavirus and coronavirus | 3/142

(2%) |

0 | 3/87

(3%) |

| Rotavirus and E. coli K99 | 5/142

(4%) |

0 | 5/87

(6%) |

| Rotavirus and C. parvum | 14/142

(10%) |

1/55

(2%) |

13/87

(15%) |

| Coronavirus and E. coli K99 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Coronavirus and C. parvum | 2/142

(1%) |

1/55

(2%) |

1/87

(1%) |

| E. coli K99 and C. parvum | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Three pathogens | 7/142

(5%) |

2/55

(4%) |

5/87

(6%) |

| Four pathogens | 1/142

(1%) |

0 | 1/87

(1%) |

*Note: Samples with only two pathogens are shown under the appropriate pair; samples with 3 or 4 pathogens are shown in the bottom two rows.

To address the possibility that multiple fecal samples from an affected farm could skew these results, the number and type of farms affected were also calculated, both for each pathogen and for combinations of pathogens. The findings for the number of farms with each pathogen, and the number of farms with different combinations of pathogens, are shown in tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Table 3. Pathogens on farms with diarrheic calves in South Carolina, 2012-2016. Number of positive farms / total number of farms (percentage of total farms).

| Pathogen | All Farms

(N=67) |

Beef Farms

(N=46) |

Dairy Farms

(N=21) |

| No pathogens | 30/67

(45%) |

22/46

(48%) |

8/21

(38%) |

| Rotavirus | 30/67

(45%) |

18/46

(39%) |

12/21

(57%) |

| Coronavirus | 12/67

(18%) |

7/46

(15%) |

5/21

(24%) |

| E. coli K99 | 6/67

(9%) |

0 | 6/21

(29%) |

| C. parvum | 19/67

(28%) |

7/46

(15%) |

12/21

(57%) |

Table 4. Pathogen combinations on farms with diarrheic calves in South Carolina, 2012-2016. Number of positive farms / total number of farms (percentage of total farms).

| Pathogen Combination* | All Farms

(N=67) |

Beef Farms

(N=46) |

Dairy Farms

(N=21) |

| No pathogens | 30/67

(45%) |

22/46

(48%) |

8/21

(38%) |

| Only one pathogen | 20/67

(30%) |

19/46

(41%) |

1/21

(5%) |

| Rotavirus and coronavirus | 2/67

(3%) |

2/46

(4%) |

0 |

| Rotavirus and E. coli K99 | 1/67

(2%) |

0 | 1/21

(5%) |

| Rotavirus and C. parvum | 4/67

(6%) |

1/46

(2%) |

3/21

(14%) |

| Coronavirus and E. coli K99 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Coronavirus and C. parvum | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| E. coli K99 and C. parvum | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Three pathogens | 9/67

(13%) |

3/46

(7%) |

6/21

(29%) |

| Four pathogens | 1/67

(2%) |

0 | 1/21

(5%) |

*Note: Samples with only two pathogens are shown under the appropriate pair; samples with three or four pathogens are shown in the bottom two rows.

Discussion

Diarrhea in the neonatal calf is a complex, multifactorial disease involving the calf, the environment, nutrition, immunology, and infectious agents. The relative prevalence of the infectious agents varies among studies due to differences in location, season, diagnostic techniques, and other factors.

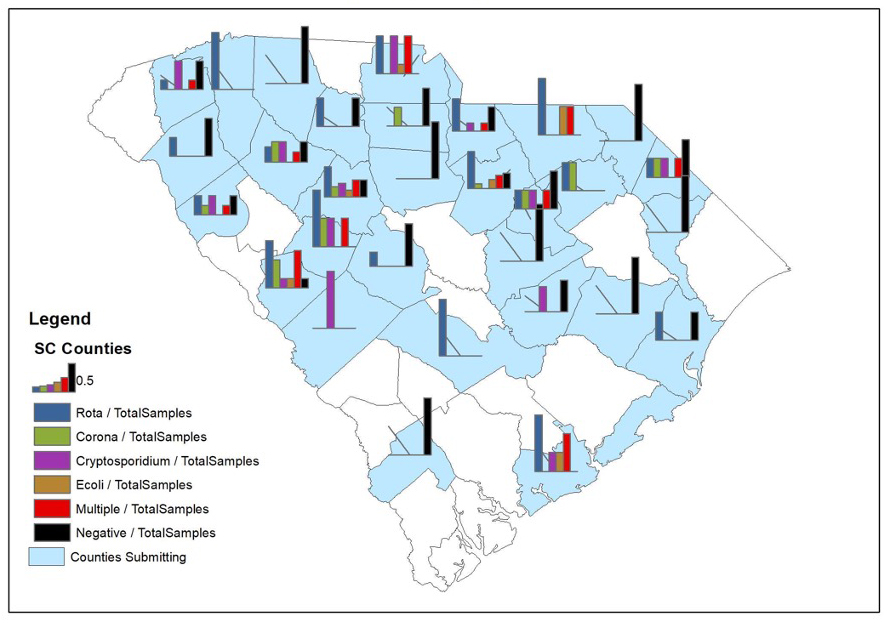

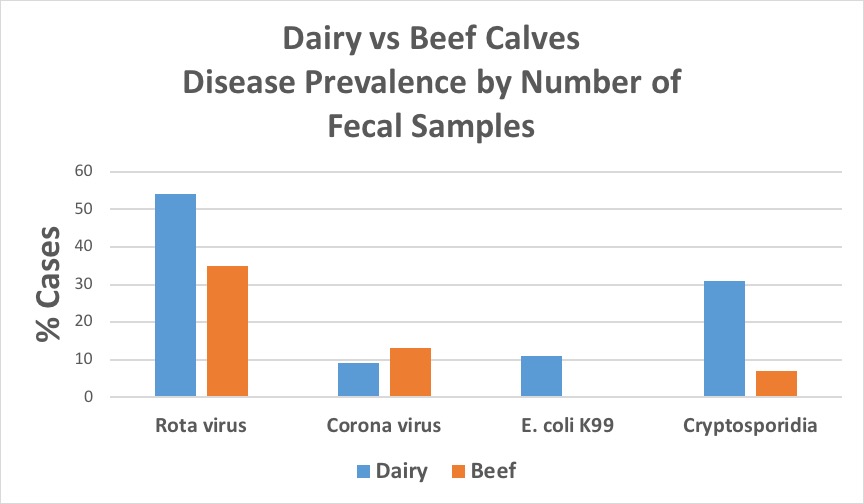

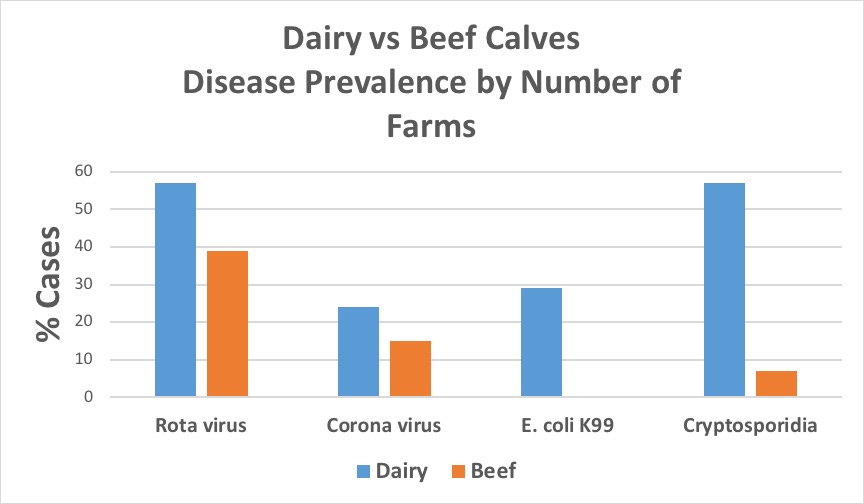

In the fecal samples examined in this study from South Carolina calves, all four pathogens were detected in all regions of the state (figure 1). Rotavirus was the most prevalent of the agents assessed in both beef and dairy fecal samples, with a higher percent positive in samples from dairy calves (54%) compared to those from beef calves (35%) (figure 2). However, when examined on a farm basis, rotavirus was still the most frequent pathogen detected on beef farms (39%), but on dairy farms, rotavirus and Cryptosporidium were found with equal frequencies (57%) (figure 3). The largest differences between beef and dairy farms were for E. coli K99 (0% beef vs. 29% dairy) and Cryptosporidium (15% beef vs. 57% dairy). Furthermore, the number of farms on which none of the four pathogens was detected varied between beef (48%) and dairy (38%) farms.

Figure 1. Rotavirus, coronavirus, E. coli K99, Cryptosporidium in fecal samples from South Carolina calves (2012-2016) by county. Image credit: Douglas Smith, Clemson University.

Figure 2. Disease prevalence by number of fecal samples for rotavirus, coronavirus, E. coli K99, and Cryptosporidium from South Carolina dairy and beef calves (2012-2016). Image credit: Douglas Smith, Clemson University.

Figure 3. Disease prevalence by number of farms for rotavirus, coronavirus, E. coli K99, and Cryptosporidium from South Carolina dairy and beef calves (2012-2016). Image credit: Douglas Smith, Clemson University.

When combinations of pathogens were examined, the most frequent combination in individual fecal samples irrespective of farm type was rotavirus and Cryptosporidium (10%). However, when examined on a farm basis, combinations of three pathogens were the most common combination (13%). Furthermore, when examined on a farm basis, combinations of three and four pathogens were much more common on dairy farms (29% and 5%, respectively) than on beef farms (7% and 0%, respectively).

Forty-five percent of the cases with a positive pathogen result correlated with histologic lesions of enteritis and/or enterocolitis. The samples (55%) with positive results but no corresponding histologic lesions show that the calf was harboring the pathogen and could be a threat to other calves in the herd or farm. Whether these calves are covertly perpetuating the disease is an area of interest and should be explored. In general, the tested dairy calves were two times more likely to be positive for any of these pathogens than beef calves. The higher incidence of disease in dairy calves is believed to be in large part due to the close quarters and potential for failure of passive transfer.

There were sixty-seven distinct farms tested, of which forty-six were beef, and twenty-one were dairy. Thirty of the sixty-seven farms tested (45%) were found to be negative for all four microorganisms. Of the thirty farms testing negative, twenty-two were beef, and eight were dairy.

References Cited

- Navarre CB, Belknap EB, Rowe SE. Differentiation of gastrointestinal diseases of calves. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice. 2000 Mar;16(1):37–57.

- Gruenberg W. Intestinal diseases in ruminants: diarrhea in neonatal ruminants. The Merck Veterinary Manual, 9th ed. Kenilworth: Merck & Co., Inc., 2005. p. 228–233.

- Cho YI, Yoon KJ. An overview of calf diarrhea-infectious etiology, diagnosis, and intervention. Journal of veterinary science. 2014 Mar;15(1):1–7.

- Foster DM, Smith GW. Pathophysiology of diarrhea in calves. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice. 2009 Mar;25(1):13–36.

This material is based upon work supported by the NIFA/USDA, under project number SC-17-207-5051-0196-111-1700528.

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the view of the USDA.