Based on research supporting the increase in memory recall and retention from teaching models emphasizing repetition and spaced-out teaching sessions of the same material, students explored sterilization techniques of medical products used in surgery and the packaging industry in three different ways and at four spacing intervals. The purpose of this brief is to explain a teaching methodology that correlated to increased learning and mastery of material after repeated exposure to the same topic at organized spacing intervals (time between sessions). Students reported increased retention and learning of material after this teaching technique. Instructor observation revealed better command of and increased confidence in the material by students following this change in teaching.

Introduction

Research in the literature on teaching and learning that links repetition to better and more embedded learning is well documented. Repetition is the recurrence of an action or event. With repetition in teaching and learning, the recurrence equates to the number of exposures to the same fundamental information, expanding that basic learning set slightly with each exposure or recurrence. Embedded learning is the idea that information becomes learned rather than memorized with recall. Embedded learning has a deeper connotation than mere recall or regurgitation.1,2,3 Additionally, there is an association between spaced-out repetition (a few days in between exposures) and deeper learning.4 Furthermore, researchers Chen and Yang clarified how repetition influences item and contextual memories during discriminative learning and suggest that multiple exposures render the details more vividly remembered and retained over time when elaborative encoding is emphasized.5 To this end, students in this course received multiple exposures (repetitions) to the same material over a 10-day period. The delivery method of these exposures changed, but the information did not. Therefore, these multiple exposures equipped the students with better recall, informational organization, and retention over time. Benjamin and Tullis stated that the advantages provided to memory by the distribution of multiple practice or study opportunities are among the most powerful effects in memory research.6 Research suggests that several factors influence learning, and one of the most important is the distribution of practice over time. Separating practice repetitions by a delay slows acquisition but enhances retention. This effect, called the spacing effect, is one of the most widely replicated results in psychology.”7

Reviewing the literature on repetition and spacing led to changing the delivery method of one section of material in a packaging science course on Packaging Perishable Products (PKSC 2010). PKSC 2010 is a course exploring the fundamental reactions taking place in perishable products, including foods and pharmaceuticals. Packaging issues regarding food, pharmaceutical, and medical packaging, product/package interactions, and packaging requirements to address basic theory in food and pharmaceutical protection are addressed. As one unit in the course, students learn sterilization techniques as they are applied to foods and medical supplies and devices. In previous semesters, the topic of sterilization techniques was a 45-minute lecture. Based on student feedback, students found sterilization techniques dull and mundane. After researching the impacts of repetition and spacing, this learning model was employed with a four-part exposure to learning. In the first exposure, students had an initial lecture on sterilization from the instructor of the course. The second exposure was another lecture from a guest lecturer who uses sterilized medical devices daily. The speaker was a surgical nurse who uses sterilized medical devices each day. She brought samples of different sutures, anchors, rods, and bandages used in surgery. Her lecture was an exciting way for students to see the fundamental information from the lecture applied to a specific field and industry. Essentially, this lecture was experiential learning and brought a professional in the field to the classroom. Finally, the third and fourth exposures introduced an assignment wherein the students prepared a formal presentation and presented the information they learned from both of the previous exposures.

Exploring research on repetition and spacing motivated the instructor to try a new technique in this course to improve student learning and engagement. After employing these techniques, students were far more engaged. They showed mastery of the information, and informal student comments from this unit supported the research regarding repetition and the spacing effect. The instructor adapted principles from Pavlik and Anderson, who discussed learning and forgetting effects on memory and stated, “However, unlike forgetting functions, which propose that forgetting is a continuous process, the learning rate in practice functions assumes some discrete increment [of learning] for each added presentation.”8

Description of Teaching Activity

In this course, an initial 45-minute lecture was taught on different sterilization techniques used in the packaging industry and the purpose of what those techniques achieve in terms of the reduction of microorganisms. PKSC 2010 is a Tuesday/Thursday course. The first lecture was on a Tuesday. Two days later (Thursday), a guest speaker from Blue Ridge Orthopedic came to present a lecture on sterilized medical supplies and devices used in surgery. This speaker has ten years of experience and assists in orthopedic surgeries and daily clinical practice. The reason she was asked to lecture in a class on packaging perishable products was two-fold: (1) she spends her days interacting with a sterile field and sterile medical products, ensuring that sterility is maintained, and proper practices are applied; (2) the guest speaker interacts with sterilized medical devices and their packaging each day. While it is important for packaging science students to learn the basics about package/product sterilization, they must also learn about any limitations occurring in surgery as a result of a breach of the sterile field or a package failure that limits the efficiency of the medical staff. For example, while the packaging and the product of Accu-Pass Suture Shuttle, Monofilament #1TM (Smith & Nephew) were both sterile and well-validated, the procedure of opening this package and removing the sutures from the packaging without violating the sterility of the product is difficult and cumbersome, especially with wet or bloody gloves. Examples and information describing product sterility and difficulty of use were demonstrated by the speaker (surgery nurse) during her lecture. She reinforced the technical sterilization information delivered in the instructor’s initial lecture, as well as demonstrated how people actually interact with the packaged medical product. Reiteration of lecture material and repeated exposure through demonstration prompted the students to think beyond the basic lecture material on sterilization techniques and encouraged them to think about the practicality of maintaining sterility. This lecture and experiential learning served as the second exposure to the topic.

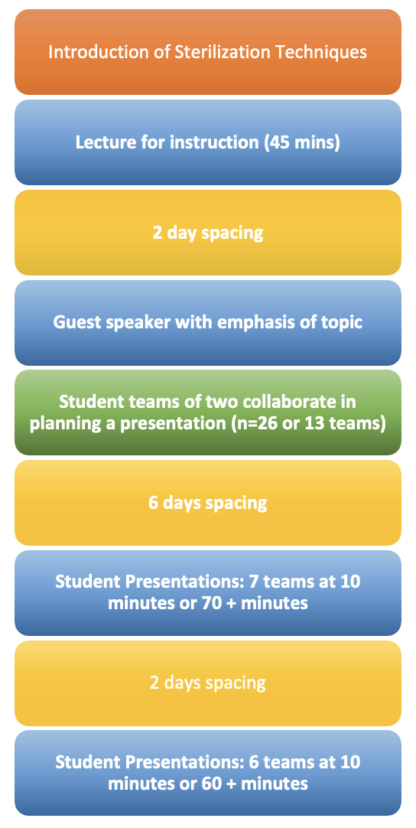

Finally, the third exposure was introduced four days after the guest lecture (Tuesday) and eight days following the initial (first exposure to the topic) 45-minute lecture on sterilization. In the third exposure, students were paired to present 10-minute, formal presentations of the information learned from the previous two lectures. Presentations took two class periods. Therefore, the presentations represented the third and fourth spaced out (Thursday – seven days later) repetition of the sterilization material (figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic showing sequence of teaching activity. Image credit: Heather Batt, Clemson University.

A combined 10-day spacing effect was used to teach a topic that was described as dull and mundane by students in previous iterations of the Packaging Perishable Products (PKSC 2010) course. A 10-day duration was chosen because the learning unit on sterilization was only one of eleven different units taught in the course. Alternatively, if the material taught or subject matter discussed was a theme throughout the entire semester, more repetitions and an overall longer spacing duration could be applied. For example, if an entire course is taught on only one topic, the instructor has sixteen weeks to teach that one topic. Thus, each week could have multiple repetitions with different spacing intervals. The instructor could experiment with repetitions of the same material in the same week, repetitions of the same material once each week for sixteen weeks, or alternating repetitions between the end of the week and the beginning of the next week or longer, etc. If the course was taught on Tuesdays and Thursdays, material A could be repeated twice that same week (2-day spacing effect). Alternatively, material A could be introduced on Tuesday and material B introduced on Thursday. The next week, material A could be repeated the next Tuesday (7-day spacing effect) and material B the next Thursday (7-day spacing). Due to the fact the instructor has sixteen weeks, repetition and spacing effects could be experimented with for the best retention and embedded learning by students.

Discussion of Outcomes

A total of twenty-seven undergraduate students enrolled in Packaging Perishable Products (PKSC 2010) were present for and took notes on a Sterilization Techniques lecture and a guest lecture on sterilization techniques for medical products. Twenty-six students then presented on a packaged medical product, how it was sterilized, and for what purpose. Figure 2 shows the students during the guest lecture. Figure 3 shows two students interacting with and inspecting a medical device. A rubric for evaluating student presentations is included in the Appendix at the end of this publication. When evaluating student presentations, it was clear that the students showed confidence and mastery of the sterilization techniques information. When evaluating questions on the following test related to sterilization techniques, students performed well and had little trouble recalling the information discussed and learned.

Students reported through informal conversation in class and during office hours how they benefitted from the repetitious learning technique when learning about sterilization and its specific application to medical products and packaging. They enjoyed the guest lecturer, who was able to apply the specific knowledge from the instructor’s lecture to real-life scenarios related to the packaging industry as well as the medical profession. Additionally, students reported the presentations given four and six days after the guest lecture were beneficial and engaging because they took the fundamental information from the first exposure and combined it with the experiential learning from the second exposure. After preparing the presentation together outside of class, they produced a presentation of work for which they had mastery and ownership, highlighting what they were most interested in from the information. When planning a formal presentation with a partner, students commented that it tied the repetitions of the information and the different teaching methods together for them. Students were instructed to choose a medical device, surgical bandage, or suture/anchor for discussion. They were required to discuss the device, including its function and package materials. They needed to explain why sterilization was required and how it was achieved. The advantages and disadvantages of their specific product and process were explained. Each couple had ten minutes in class to present and an additional two minutes to answer questions about their information. Due to time constraints, the presentations required two class days. Each presentation was due on the same day to ensure no group benefitted from the feedback another couple received because they presented earlier than other groups in the schedule.

Students indicated they learned more through this unit than they would have if they were assessed in a more traditional manner with a written test. The repetitions in the learning activities helped students learn this material in class rather than hearing it once and then having to try to learn it on their own. Furthermore, there were a few students repeating this course, and they were able to specifically comment that this was a far more beneficial and engaging learning format—with spaced repetition, guest speaker, and presentation—than in previous semesters wherein this section of lecture felt more like an afterthought than an important unit. Due to a smaller class size during this semester as compared to other semesters, it was possible to have students present during lecture time. During the presentations, the instructor observed increased confidence in the students as it related to their learning and understanding of the sterilization material. In previous semesters, this confidence was not evidenced. The repetition allowed the students to be more comfortable overall with the subject matter.

Reflection of Outcomes

The brief review of literature at the beginning of this discussion spans the subjects of math, foreign languages, psychology, computer coding, and now packaging science. As Chen and Yang reported, exposing students to multiple repetitions in learning correlates with better memory retention and more detailed recall.5 Harvard researchers elaborated on the association between spaced out repetition (a few days in between exposures) and deeper learning. “With the spacing effect, if you take information in small amounts and repeat it, it encodes that information in your memory.”4 The spacing effect resulting in more embedded memory is corroborated by various researchers. Thus, repetitious learning and spacing between repetitions are not new. However, applying this technique to difficult or new subject matter could be especially beneficial for student learning and retention of important concepts that may be difficult to learn in a traditional lecture-style course. The impact of using repetition in PKSC 2010 – Packaging Perishable Products course has transferred to other courses. Understanding this section of course material was previously weakly received by students, the instructor sought to improve student learning. The research clearly revealed a new technique to try. The effectiveness of repetition and spacing with learning and retention nullified the risk of trying something new. The improvement of both attitude and aptitude with regard to the material on sterilization techniques supports trying this teaching technique. After observing the success of this technique, repetitions and different spacing effects are now regularly employed in the instructor’s other courses. Students have commented informally and on midterm evaluations about how much they appreciate the repetitions at the beginning of each class and repeated spaced-out review with which class now begins.

Prior to using repetition and spacing in PKSC 2010 – Packaging Perishable Products, the instructor observed that students were not engaged with the material on sterilization techniques. Students seemed unimpressed by the techniques that render medical devices and foods commercially sterile, and largely, it was noted that students simply took this sterilization for granted. After employing repetitious teaching with spaced-out iterations, observations showed more student interest and excitement. These techniques have broad application in all courses to promote student learning and retention. Changes to course content delivery methods have been made in all of the instructor’s courses.

Discussion of Potential for Adoption in Other Courses

The application of repetitious learning with the spacing effect is widespread and can be used in any classroom environment or any repeated learning exercise assigned to students. Typically, laboratory sessions inherently embrace this repetitious learning model by reinforcing lecture concepts with practical hands-on practice. However, incorporating this intentional repetition in lecture-only courses is unique. The model for the number of repetitions and the spacing between them can vary based on how many topics the instructor presents in one semester. For example, if an instructor has ten topics to teach in a 16-week semester, repetitions would generally be two or three per week, and the spacing between them would be one day. However, if a class was taught to cover limited material more in-depth throughout the semester, perhaps in the case of graduate-level courses or seminars, and the number of different topics presented in sixteen weeks was smaller, then the number of repetitions could be higher, but the spacing effect could remain the same at every other day. Again, if four topics were covered in sixteen weeks, the instructor could repeatedly teach that material in different manners many more times and at different spacings than if the instructor taught ten topics.

Potential next steps include integrating more repeated exposure in courses with difficult material or new concepts. The use of student presentations worked to bring together the other course content through lecture and demonstration, but only because this particular course had a small enrollment. Previous semesters prohibited student presentations due to larger class sizes. For example, when enrollment is close to eighty students, 10-minute presentations in groups of two students would take approximately three weeks of class. Considering the course has many different topics to cover, a larger class size prohibits the use of the third and fourth repetition (formal presentation).

References Cited

- Rock I. Repetition and learning. Scientific American. 1958 Aug;199(2):68–76.

- Nelson T. Repetition and depth of processing. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1977 Apr;16(2):151–171.

- Northbrook J, Allen D, Conklin K. ‘Did you see that?’—the role of repetition and enhancement on lexical bundle processing in English learning materials. Applied Linguistics. 2022 Jun;43(3):453–472.

- Tamer M. Repetition, repetition, repetition. Cambridge (MI): Harvard Graduate School of Education, Ed Magazine; 2010 Jan 26. [accessed 2023 Feb]. https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/ed/10/01/repetition-repetition-repetition.

- Chen H, Yang J. Multiple exposures enhance both item memory and contextual memory over time. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020 Dec;11:3312.

- Benjamin A, Tullis J. What makes distributed practice effective? Cognitive Psychology. 2010 Nov;61(3):228–247.

- Walsh M, Krusmark M, Jastrembski T, Hansen DA, Honn KA, Gunzelmann G. Enhancing learning and retention through the distribution of practice repetitions across multiple sessions. Memory & Cognition 2023 Feb;51(2):455–472.

- Pavlik P Jr., Anderson J. Practice and forgetting effects on vocabulary memory: an activation-based model of the spacing effect. Cognitive Science. 2005 Jul;29(4):559–586.

Appendix

Rubric for Evaluation Student Presentations

Student Name: _______________________ Score: ______%

| Category | Scoring Criteria | Total Points | Score |

| Content

(65 points) |

Introduction is attention-getting, lays out the topic well, and establishes a framework for the rest of the presentation. | 10 | |

| Technical terms are well-defined in language appropriate for the target audience. | 7 | ||

| Presentation contains accurate information. Material included is relevant to the overall topic/purpose. Appropriate amount of material is prepared, and points made reflect well their relative importance. | 45 | ||

| There is an obvious conclusion highlighting the most important points of the presentation. | 8 | ||

| Presentation

(35 points) |

Speaker maintains good eye contact with the audience and is appropriately animated (e.g., gestures, moving around, etc.). | 5 | |

| Speaker uses a clear, audible voice and is poised, controlled, and smooth. Shows they have practiced and are prepared. | 5 | ||

| Visual aids are well-prepared, informative, effective, and not distracting. | 5 | ||

| Length of presentation is within the assigned time limits, and distribution of effort is even. | 5 | ||

| Appropriate business casual dress. | 5 | ||

| Information is presented in a logical sequence. | 5 | ||

| Score | Total Points | 100 |

Notes: